The Mauryan Empire (322–185 BCE) was the first empire to encompass most of the Indian subcontinent. Founded by Chandragupta Maurya with the guidance of his mentor Chanakya (Kautilya), it replaced the Nanda Dynasty of Magadha. The empire reached its zenith under Emperor Ashoka, who expanded it from Afghanistan in the west to Bangladesh in the east, and from the Himalayas to the Deccan. It was renowned for its highly centralized administration, the treatise on statecraft Arthashastra, and the spread of Buddhism. The empire collapsed in 185 BCE when the last emperor, Brihadratha, was assassinated by his general Pushyamitra Shunga.| Feature | Details |

| Duration | 322 – 185 BCE |

| Capital | Pataliputra (Patna) |

| Founder | Chandragupta Maurya |

| Key Rulers | Chandragupta, Bindusara, Ashoka |

| Royal Emblem | Lion Capital (Sarnath) / Peacock (Mayura) |

| Key Texts | Arthashastra (Kautilya), Indica (Megasthenes) |

| Religion | Jainism (Chandragupta), Ajivika (Bindusara), Buddhism (Ashoka) |

| Currency | Punch-marked Silver Coins (Karshapana) |

| End | Assassination of Brihadratha (185 BCE) |

The Rise: Chanakya’s Revenge

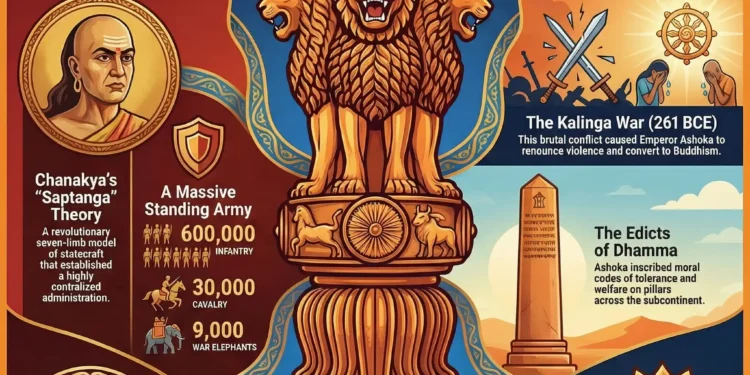

The empire’s origin lies in the humiliation of the scholar Chanakya by the Nanda King Dhana Nanda. Chanakya swore to destroy the dynasty and groomed a young Chandragupta to fulfill this vow.

- Defeating the Nandas: Using guerrilla tactics and attacking the borders first (Mandala theory), Chandragupta seized Pataliputra in 322 BCE.

- Defeating Seleucus: In 305 BCE, Chandragupta defeated Seleucus Nicator (Alexander’s general), securing the Northwest (Afghanistan) and receiving the Greek ambassador Megasthenes.

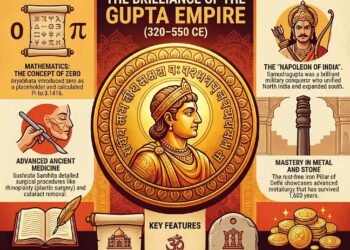

Reign of Gupta Empire: The Golden Age of Ancient India

The Apex: Ashoka the Great

After Chandragupta’s son Bindusara expanded the empire southward (earning the title Amitraghata or Slayer of Foes), Ashoka took the throne.

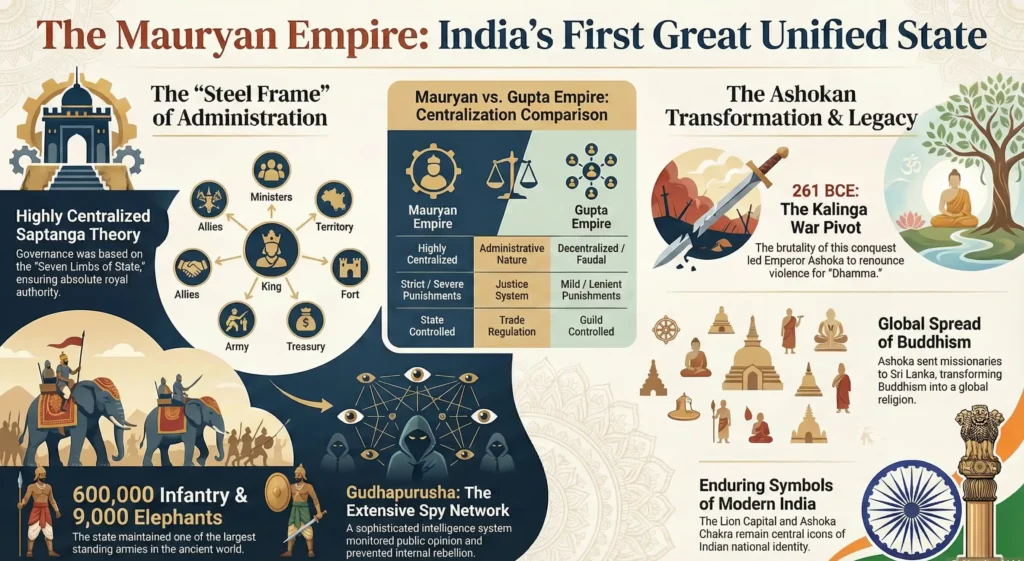

- Kalinga War (261 BCE): The brutal conquest of Kalinga led Ashoka to renounce violence.

- Dhamma: He established a code of ethics based on tolerance and welfare, inscribed on Rock Edicts and Pillars across the empire.

- Missionary Work: He sent his children, Mahinda and Sanghamitta, to Sri Lanka, turning Buddhism into a global religion.

Kalinga War c. 261 BCE: The Battle That Changed Ashoka Forever

Administration: The Steel Frame

The Mauryan administration was a marvel of centralization, primarily based on the Saptanga Theory (Seven Limbs of State) from the Arthashastra.

- The King: The supreme authority, aided by a Council of Ministers (Mantriparishad).

- Espionage: A vast network of spies (Gudhapurusha) kept the king informed of public opinion and rebellion.

- City Administration: Megasthenes described Pataliputra as being run by a commission of 30 members divided into 6 boards (industry, foreigners, birth/death registration, trade, goods, tax).

- Army: A massive standing army of 600,000 infantry, 30,000 cavalry, and 9,000 elephants.

Economy and Society

- Agriculture: The state controlled agriculture (Crown lands called Sita) and maintained irrigation projects like the Sudarshana Lake in Gujarat.

- Trade: The Uttarapatha (Northern High Road) connected Taxila to Pataliputra, facilitating trade with the Greek world.

- Art: This era introduced stone architecture to India, replacing wood. The polished sandstone pillars and the Sanchi Stupa are enduring examples.

Reign of Chandragupta Maurya 321-297 BCE: The First Empire of India

The Decline: Why did it fall?

After Ashoka’s death in 232 BCE, the empire disintegrated rapidly.

- Weak Successors: Kings like Dasharatha and Brihadratha lacked the strength to hold the vast empire.

- Brahmanical Reaction: Some historians argue that Ashoka’s ban on animal sacrifices alienated the Brahmins, leading to the Shunga Coup.

- Financial Crisis: Excessive donations to Buddhist monasteries and a huge standing army drained the treasury.

- Foreign Invasions: The Greeks (Bactrians) began attacking the unguarded Northwest frontier.

Quick Comparison Table: Mauryan vs. Gupta Administration

| Feature | Mauryan Empire | Gupta Empire |

| Nature | Highly Centralized | Decentralized / Feudal |

| Justice | Strict / Severe Punishments | Mild / Lenient Punishments |

| Spies | Extensive Network | Less Prominent |

| Land Revenue | High (1/4 to 1/6) | Moderate (1/6) |

| Trade | State Controlled | Guild Controlled |

Curious Indian: Fast Facts

- The First Marriage Alliance: Chandragupta’s marriage to the daughter of Seleucus Nicator is considered the first documented international marriage alliance in Indian history.

- Censorship: The Mauryan state regulated even the prices of goods and the weights used in markets.

- Yakshi Statue: The famous Didarganj Yakshi, a masterpiece of Mauryan polish, was found near Patna, showcasing the era’s artistic brilliance.

- No Slavery? Megasthenes famously wrote that “there are no slaves in India,” likely because the treatment of Indian Dasas (servants) was much more humane than Greek slavery.

Conclusion

The Mauryan Empire was a political experiment that succeeded beyond measure. It gave India its first unified identity, its first major road networks, and a legacy of administrative statecraft that is still studied today. While the empire fell, symbols like the Ashoka Chakra and the Lion Capital ensure that the Mauryan legacy lives on in the heart of modern India.

Reign of Ashoka: The Emperor Who Chose Peace

If you think you have remembered everything about this topic take this QUIZ

Results

#1. Who founded the Mauryan Empire after replacing the Nanda Dynasty?

#2. What was the capital city of the Mauryan Empire?

#3. Which Greek ambassador visited the Mauryan court and wrote the text Indica?

#4. Which brutal conflict in 261 BCE led Emperor Ashoka to renounce violence and adopt Dhamma?

#5. What was the name of the primary currency used during the Mauryan Empire?

#6. The Mauryan administration’s ‘Seven Limbs of State’ (Saptanga Theory) is detailed in which text authored by Kautilya?

#7. What term was used to describe the Crown lands where the state controlled agriculture?

#8. Who was the last Mauryan emperor, assassinated by his general Pushyamitra Shunga in 185 BCE?

Who was the last Mauryan Emperor?

Brihadratha was the last emperor, assassinated in 185 BCE.

What is the Saptanga Theory?

It is Chanakya’s theory that a state has seven limbs: King, Minister, Territory, Fort, Treasury, Army, and Ally.

Who wrote the Indica?

Megasthenes, the Greek ambassador to Chandragupta’s court.

Did Ashoka ban the death penalty?

No, but he granted a three-day respite to prisoners on death row to prepare for the afterlife.

What was the main currency of the Mauryans?

The Karshapana (Punch-marked silver coin).