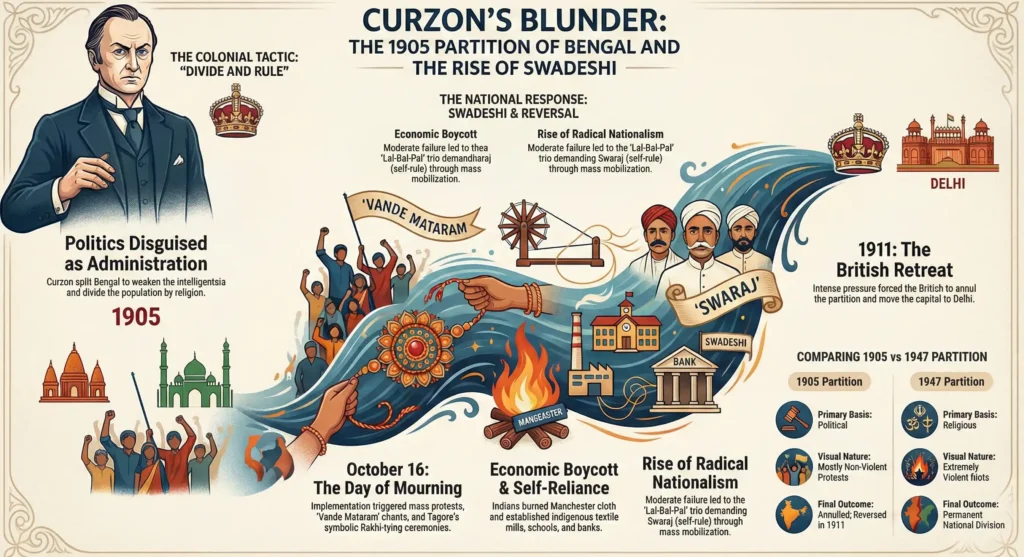

The Partition of Bengal 1905 was a controversial administrative decision taken by the British Viceroy, Lord Curzon. Officially, the British claimed that the province of Bengal (with 80 million people) was too large to be governed efficiently. However, the real motive was political: to weaken the growing center of Indian nationalism in Calcutta by dividing the Bengali-speaking population along religious lines—Hindus in the West and Muslims in the East. Announced on July 19, 1905, and implemented on October 16, 1905, it triggered massive protests, leading to the Swadeshi Movement, the boycott of British goods, and the rise of radical nationalism. The partition was so unpopular that the British were forced to annul it in 1911.| Feature | Details |

| Date of Announcement | July 19, 1905 |

| Date of Implementation | October 16, 1905 (Raksha Bandhan Day) |

| Viceroy Responsible | Lord Curzon |

| Official Reason | Administrative Efficiency |

| Real Motive | Divide and Rule (Weaken Nationalism) |

| Key Movement Triggered | Swadeshi Movement |

| Outcome | Annulled in 1911 (Capital moved to Delhi) |

The Logic of Division

At the turn of the 20th century, Bengal was the nerve center of Indian politics. It included present-day West Bengal, Bangladesh, Bihar, and Odisha. Lord Curzon, an arrogant imperialist, viewed the Bengali intelligentsia as a threat to the Raj. In a private letter, he admitted, “Bengal united is a power; Bengal divided will pull in several different ways.”

The plan was cunning. It created two new provinces:

- Bengal (West): Hindu-majority, with Calcutta as the capital.

- Eastern Bengal and Assam: Muslim-majority, with Dhaka as the capital.This successfully pitted the economic interests of the Muslim peasantry in the East against the Hindu landlords and professionals in the West.

The Day of Mourning: October 16, 1905

When the partition came into effect on October 16, 1905, Bengal went into mourning. No fires were lit in kitchens (Arandhan). People walked barefoot to the Ganges to take a holy dip, singing patriotic songs. The streets of Calcutta echoed with a new cry: “Vande Mataram” (Mother, I bow to thee), taken from Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s novel Anandmath. This song became the anthem of the resistance.

Muslim League Founded 1906: The Beginning of Communal Politics in India

The Rakhi Protest

One of the most poetic protests was organized by Rabindranath Tagore. He declared the day of partition as a day of unity. He urged Hindus and Muslims to tie Rakhis (threads of protection) on each other’s wrists to symbolize the unbreakable bond between the two communities. Thousands gathered on the streets, tying Rakhis and defying the British attempt to split them.

The Birth of Swadeshi

The anger soon turned into action. The leaders of Bengal realized that petitions and prayers would not work. They launched the Swadeshi Movement—the boycott of British goods and the promotion of Indian goods.

- Bonfires: Expensive Manchester cloth was thrown into bonfires.

- Indigenous Industry: Indian textile mills, soap factories, and banks were set up.

- National Education: Students boycotted British schools. The National Council of Education (which later became Jadavpur University) was established to provide education on national lines.

The Rise of Extremism

The moderate leadership of the Congress, which believed in “constitutional methods,” failed to stop the partition. This failure led to the rise of the “Extremist” faction led by the trio Lal-Bal-Pal (Lala Lajpat Rai, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, and Bipin Chandra Pal). They demanded Swaraj (self-rule) and open defiance, transforming the Congress from a debating club into a mass movement.

Jallianwala Bagh Massacre 1919: Inside the Tragedy That Ignited a Revolution

The Annulment: A Partial Victory

The protests were so intense and sustained that the British administration paralyzed. Finally, in 1911, King George V visited India for the Delhi Durbar. He announced the annulment of the Partition of Bengal. The Bengali-speaking areas were reunited. However, to crush the political power of Bengal forever, the British simultaneously shifted the capital of India from Calcutta to Delhi.

Quick Comparison Table: 1905 Partition vs. 1947 Partition

| Feature | Partition of Bengal (1905) | Partition of India (1947) |

| Executor | Lord Curzon | Lord Mountbatten |

| Outcome | Annulled/Reversed in 1911 | Permanent Division |

| Violence | Mostly Non-Violent (Protests) | Extremely Violent (Communal Riots) |

| Basis | Administrative/Political (Divide & Rule) | Religious (Two-Nation Theory) |

| Legacy | United Bengal against British | Divided Bengal into West Bengal & East Pakistan |

Curious Indian: Fast Facts

- The First National Flag: During the Swadeshi movement, a tricolor flag (red, yellow, green) was designed, with eight lotuses representing the eight provinces of British India and a crescent moon and sun for Hindu-Muslim unity.

- Amar Sonar Bangla: During the protests, Rabindranath Tagore wrote the song Amar Sonar Bangla (My Golden Bengal). Decades later, in 1971, this became the national anthem of independent Bangladesh.

- Barisal Conference: In 1906, the police brutally beat up delegates at the Bengal Provincial Conference in Barisal for shouting “Vande Mataram,” marking the first major police atrocity of the movement.

- Weaving as Protest: Many Bengali women smashed their glass bangles (which were imported) and started wearing shell bangles (Shankha) made locally.

Conclusion

The Partition of Bengal 1905 was a classic case of imperial overreach. Lord Curzon wanted to divide Bengal to weaken it, but he ended up uniting India. The Swadeshi movement that rose from the ashes of 1905 taught Indians the power of economic boycott and mass mobilization—lessons that Gandhi would later perfect on a national scale. It proved that a determined people could force the mightiest empire on earth to retreat.

Non-Cooperation Movement 1920-1922: The Day India Said “No” to the British

If you think you have remembered everything about this topic take this QUIZ

Results

#1. Which British Viceroy was responsible for the Partition of Bengal in 1905?

#2. On which date was the Partition of Bengal officially implemented, observed as a day of mourning?

#3. What was the official reason given by the British for partitioning Bengal?

#4. Which song, taken from Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s novel Anandmath, became the anthem of the resistance?

#5. Who encouraged Hindus and Muslims to tie ‘Rakhis’ on each other’s wrists as a symbol of unity during the protests?

#6. The Partition of Bengal triggered which major political movement involving the boycott of British goods?

#7. In which year was the Partition of Bengal annulled by King George V?

#8. Rabindranath Tagore’s song “Amar Sonar Bangla,” written during the protests, later became the national anthem of which country?

The Midnight of August 15: Freedom, Partition, and the Blood on the Map

Why did Lord Curzon partition Bengal in 1905?

Curzon claimed it was for “administrative efficiency” as Bengal was too large, but the real reason was to weaken the Bengali nationalist movement by dividing Hindus and Muslims.

When was the Partition of Bengal annulled?

It was annulled in 1911 by King George V during the Delhi Durbar.

What was the Swadeshi Movement?

It was a movement launched in reaction to the partition, advocating the boycott of British goods and the use of Indian-made (Swadeshi) products.

How did Rabindranath Tagore protest the partition?

Tagore organized the Rakhi Bandhan festival, encouraging Hindus and Muslims to tie Rakhis on each other’s wrists as a symbol of unity.

What happened to the capital of India in 1911?

Along with the annulment of the partition, the British shifted the capital of India from Calcutta to Delhi to reduce the influence of Bengali nationalism.