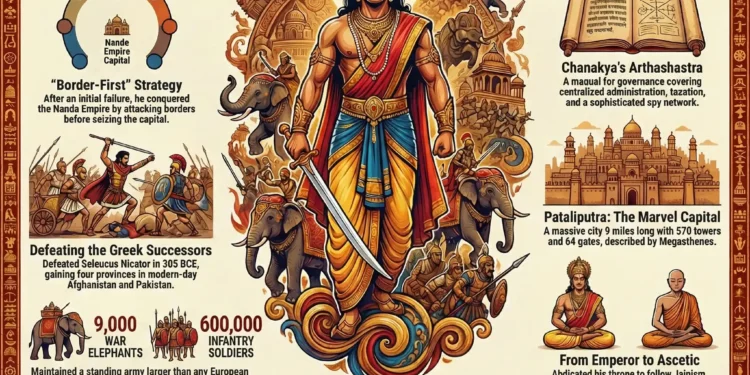

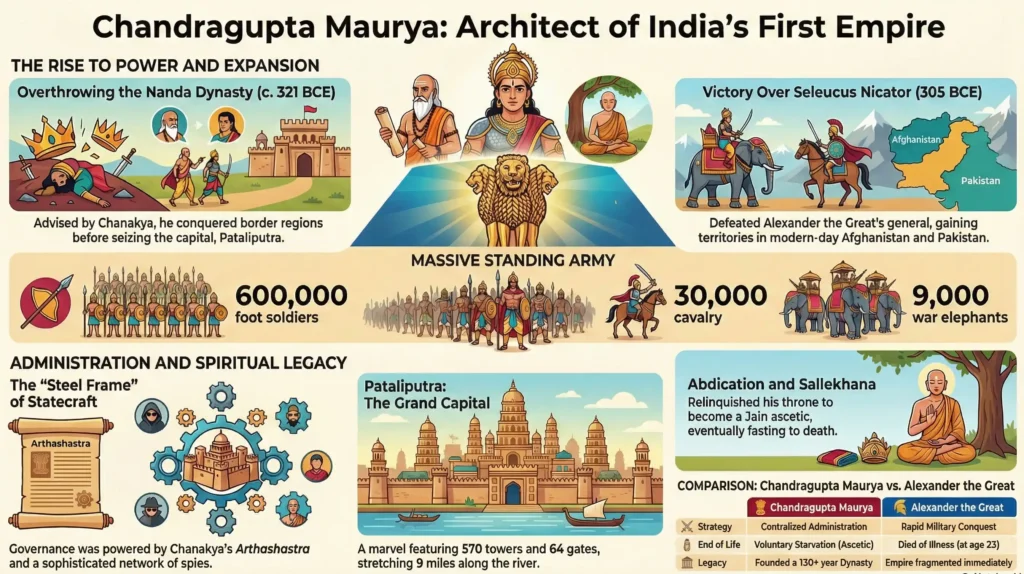

Chandragupta Maurya (ruled c. 321–297 BCE) was the founder of the Mauryan Empire, the first pan-Indian empire in history. Guided by his brilliant mentor Chanakya (Kautilya), he overthrew the oppressive Nanda dynasty of Magadha and seized the capital, Pataliputra. He then turned his attention to the Northwest, defeating Seleucus Nicator (Alexander the Great's general) in 305 BCE, securing territories in modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan. His reign is noted for its highly efficient, centralized administration as detailed in Chanakya's Arthashastra and the accounts of the Greek ambassador Megasthenes (Indica). In his later years, Chandragupta famously abdicated the throne, converted to Jainism, and traveled to Shravanabelagola (Karnataka), where he fasted to death (Sallekhana).| Feature | Details |

| Reign Dates | c. 321 – 297 BCE |

| Dynasty | Mauryan Dynasty |

| Mentor/Prime Minister | Chanakya (Vishnugupta/Kautilya) |

| Capital | Pataliputra (Patna) |

| Key Defeated Enemy | Dhana Nanda (Nandas) & Seleucus Nicator (Greeks) |

| Treaty Gain | Arachosia (Kandahar), Gedrosia (Baluchistan), Paropamisadae (Kabul) |

| Greek Ambassador | Megasthenes |

| Literary Sources | Arthashastra, Indica, Mudrarakshasa |

| End of Life | Jain Ascetic (Sallekhana) at Shravanabelagola |

The Rise: Chanakya’s Vow

The story begins with an insult. Chanakya, a teacher at Takshashila, was humiliated by King Dhana Nanda in Pataliputra. He swore to untie his shikha (topknot) only after destroying the Nanda dynasty. He found a young boy, Chandragupta, playing a game of “Royal Court” with his friends. Seeing his potential, Chanakya took him to Takshashila, trained him in warfare and statecraft, and prepared him to be a king.

Reign of Samudragupta 335-375 CE: The Napoleon of India

Conquest of Magadha

Chandragupta’s first attempt to attack the center of the Nanda empire failed. Learning from a mother scolding her child for eating the hot center of a cake instead of the cool edges, Chanakya changed strategy. They attacked the borders first, gradually moving inward. Around 321 BCE, Chandragupta defeated the Nandas and claimed the throne of Magadha.

The Greek Conflict: Seleucus Nicator

After Alexander the Great’s death in 323 BCE, his general Seleucus Nicator controlled the eastern part of his empire (Syria to India). In 305 BCE, Seleucus crossed the Indus to recover Indian territories. Chandragupta met him with a massive army.

- The Treaty: Seleucus was defeated and forced to sign a humiliating treaty. He ceded four provinces (Herat, Kandahar, Kabul, and Baluchistan) to Chandragupta.

- The Exchange: In return, Chandragupta gave him 500 war elephants, which Seleucus later used to win the Battle of Ipsus in the West.

- Marriage Alliance: It is believed that Chandragupta married Seleucus’s daughter (often named Helena in folklore).

Administration: The Steel Frame

Chandragupta established a highly centralized state, possibly the most organized in ancient history.

- Arthashastra: Written by Chanakya, this text served as the manual for governance, covering everything from spy networks to tax collection.

- Espionage: The state relied heavily on spies (Gudhapurusha)—including poison damsels (Vishkanyas)—to keep the king informed and safe.

- Pataliputra: The capital was a marvel. Megasthenes described it as a city 9 miles long and 1.5 miles wide, surrounded by a wooden wall with 64 gates and 570 towers.

Reign of Ashoka: The Emperor Who Chose Peace

Megasthenes and Indica

The Greek ambassador Megasthenes lived in Pataliputra and wrote Indica. Although the original text is lost, fragments survive in later Greek writings. He noted:

- India had no slavery (a debated point).

- Society was divided into 7 castes (philosophers, farmers, herdsmen, artisans, soldiers, overseers, councillors).

- The King was guarded by a bodyguard of women.

The Jain End: Sallekhana

According to Jain tradition, a 12-year famine hit the empire. Deeply affected, Chandragupta abdicated his throne in favor of his son Bindusara. He became a disciple of the Jain saint Bhadrabahu and migrated to the South (Shravanabelagola). There, he performed Sallekhana (fasting to death), ending his life as an ascetic on Chandragiri Hill.

Reign of Akbar 1556-1605: The Golden Age of the Mughal Empire

Quick Comparison Table: Chandragupta Maurya vs. Alexander the Great

| Feature | Chandragupta Maurya | Alexander the Great |

| Ambition | Unified India | World Conquest |

| Strategy | Centralized Administration | Rapid Military Conquest |

| End of Life | Voluntary Starvation (Ascetic) | Died of Illness (at 32) |

| Legacy | Founded a Dynasty (130+ years) | Empire Fragmented immediately |

| Mentor | Chanakya (Realist/Statecraft) | Aristotle (Philosopher) |

Curious Indian: Fast Facts

- The Name: He is referred to as Sandrocottus in Greek texts. It was Sir William Jones who first identified Sandrocottus as Chandragupta Maurya in 1793, linking Indian and Greek history.

- The Army: Pliny the Elder wrote that Chandragupta maintained a standing army of 600,000 foot soldiers, 30,000 cavalry, and 9,000 elephants—a force larger than any European army of antiquity.

- Sudarshana Lake: His governor Pushyagupta built the famous Sudarshana Lake in Girnar (Gujarat) for irrigation, highlighting the empire’s focus on agriculture.

Conclusion

The Reign of Chandragupta Maurya was the dawn of Indian political unity. He proved that a fragmented subcontinent could be welded into a single powerful entity. His life trajectory—from a commoner to an emperor to a naked ascetic—remains one of the most fascinating arcs in world history. He left behind not just a kingdom for his grandson Ashoka, but a blueprint for how to rule India.

Foundation of the Vijayanagara Empire: The Rise of Hampi

If you think you have remembered everything about this topic take this QUIZ

Results

#1. Who was the mentor and prime minister who guided Chandragupta Maurya to overthrow the Nanda dynasty?

#2. In 305 BCE, Chandragupta Maurya defeated which Greek general, securing territories in Afghanistan?

#3. Which Greek ambassador visited Chandragupta’s court and wrote the book ‘Indica’?

#4. In his later years, Chandragupta abdicated the throne and traveled to which place to become a Jain ascetic?

#5. Which ancient Greek name is used to refer to Chandragupta Maurya in historical texts?

#6. Chandragupta Maurya overthrew which oppressive dynasty to seize the throne of Magadha?

#7. The practice of fasting to death adopted by Chandragupta in his final days is known in Jainism as:

Who was the mentor of Chandragupta Maurya?

Chanakya (also known as Kautilya or Vishnugupta) was his mentor and Prime Minister.

Which Greek general did Chandragupta defeat?

He defeated Seleucus Nicator in 305 BCE.

What book provides detailed information about Mauryan administration?

The Arthashastra by Chanakya (Kautilya).

How did Chandragupta Maurya die?

He died by performing Sallekhana (ritual fasting to death) at Shravanabelagola as a Jain ascetic.

What was the capital of the Mauryan Empire?

The capital was Pataliputra (modern-day Patna).