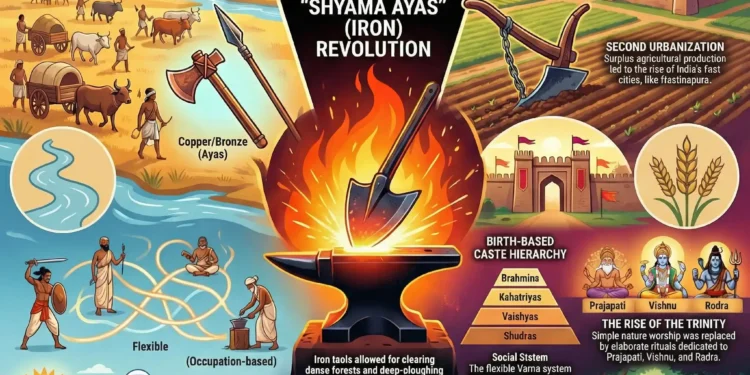

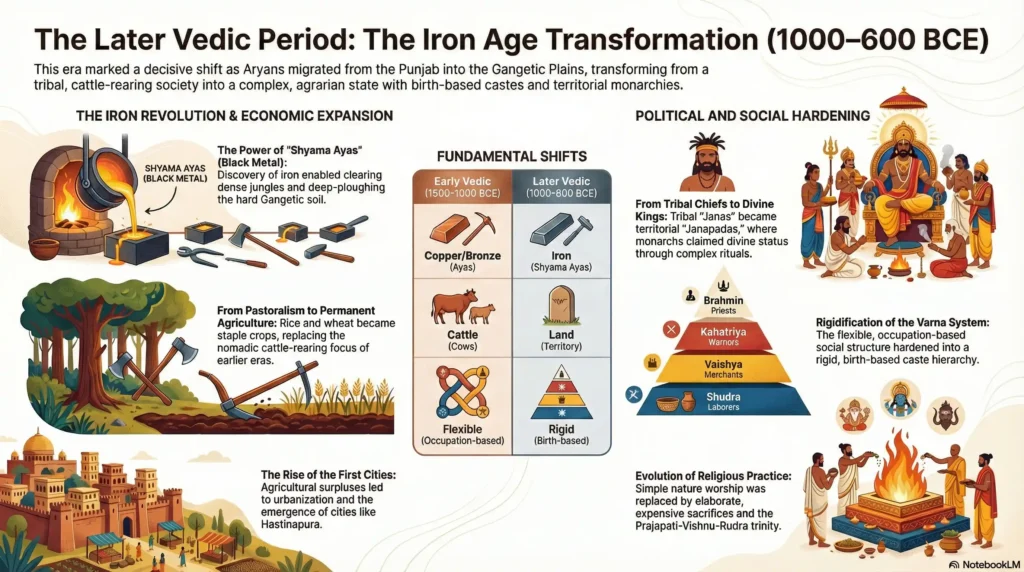

The Later Vedic Period (c. 1000–600 BCE) marks a decisive shift in Indian history. Unlike the nomadic, cattle-rearing society of the Early Vedic Age, this era saw the Aryans expand eastward from the Sapta Sindhu region into the fertile Gangetic Plains (Western UP, Delhi, Haryana). This expansion was driven by the discovery of Iron (Shyama Ayas), which allowed for the clearing of dense forests and the use of deep-ploughing agriculture. Political life transitioned from tribal assemblies to territorial kingdoms called Janapadas. The simple nature worship of the Rigveda gave way to elaborate rituals, the rise of the Prajapati-Vishnu-Rudra trinity, and the rigidification of the Varna system into a birth-based caste hierarchy.| Feature | Details |

| Duration | c. 1000 – 600 BCE |

| Core Region | Gangetic Plain (Kuru-Panchala Region) |

| Key Discovery | Iron (Shyama Ayas or Krishna Ayas) |

| Primary Economic Activity | Agriculture (Rice, Wheat, Barley) |

| Pottery Style | Painted Grey Ware (PGW) |

| Political Unit | Janapada (Territorial Kingdom) |

| New Scriptures | Samaveda, Yajurveda, Atharvaveda, Brahmanas, Upanishads |

| Key Deities | Prajapati (Creator), Vishnu (Preserver), Rudra (Destroyer) |

The Great Migration: Into the Heart of India

The Aryans of the Early Vedic period lived in the Sapta Sindhu (Land of Seven Rivers – Punjab/Indus region). In the Later Vedic period, they moved eastward into the Gangetic-Yamuna Doab.

- Role of Iron: The dense forests of the Gangetic plain were impenetrable with copper or bronze tools. The discovery of Iron around 1000 BCE changed everything. Iron axes cleared the jungles, and iron-tipped ploughshares turned the hard soil, making the region the “breadbasket” of India.

- Kuru-Panchala: The Bharatas and Purus merged to form the Kurus (ruling Delhi/Haryana), while the Panchalas ruled modern western UP. These became the most powerful tribes of the era.

Life of Buddha c. 563-483 BCE: The Journey to Enlightenment

Political Evolution: From Jana to Janapada

The tribal identity (Jana) was replaced by a territorial identity (Janapada). The king (Rajan) was no longer just a tribal chief but a territorial monarch.

- Divine Kingship: Kings began to claim divine status. Rituals like the Rajasuya (consecration ceremony), Ashvamedha (horse sacrifice for territory), and Vajapeya (chariot race) were performed to legitimize their power.

- Decline of Assemblies: The popular tribal assemblies like the Sabha and Samiti lost their power and became dominated by chiefs and rich nobles. The Vidatha (the oldest assembly) completely disappeared.

Social Structure: The Hardening of Varna

The flexible Varna system of the Early Vedic age became rigid and hereditary.

- Brahmins: The priests who conducted the complex rituals became supreme.

- Kshatriyas: The warrior-kings who protected the land asserted their dominance.

- Vaishyas: The agriculturists and traders who paid the taxes (Bali and Bhaga).

- Shudras: The servers of the other three castes. They were denied the right to wear the sacred thread (Janeu) and recite the Vedas.

- Gotra System: The concept of Gotra (lineage from a common ancestor) appeared, enforcing strict rules against marriage within the same clan (Sagotra marriage was banned).

- Ashramas: The four stages of life (Brahmacharya, Grihastha, Vanaprastha, Sannyasa) were formulated, though Sannyasa was not yet strictly established.

Reign of Chandragupta Maurya 321-297 BCE: The First Empire of India

Economy: The Iron Age Revolution

Agriculture became the backbone of the economy.

- Crops: While barley was still grown, Rice (Vrihi) and Wheat (Godhuma) became the staple crops. The use of manure was known.

- Painted Grey Ware (PGW): This specific type of pottery identifies the archaeological sites of this period (like Hastinapura and Atranjikhera).

- Urbanization: Towards the end of this period (c. 600 BCE), the surplus production led to the rise of the first cities (Nagar) like Hastinapura and Kausambi, marking the start of the Second Urbanization.

Religion: From Nature to Rituals

The simple prayers to Indra and Agni were replaced by complex, expensive sacrifices (Yajnas) that could last for years.

- New Gods: The Early Vedic gods lost their importance.

- Prajapati (The Creator) became supreme.

- Vishnu (The Preserver) and Rudra (The Destroyer – an early form of Shiva) gained prominence.

- Pushan became the god of the Shudras.

- The Reaction (Upanishads): Towards the end of this period, a philosophical reaction against the meaningless rituals began. The Upanishads (c. 600 BCE) focused on spiritual knowledge (Jnana) and the relationship between the Soul (Atman) and the Ultimate Reality (Brahman), laying the foundation for Vedanta.

Literature: The Three New Vedas

While the Rigveda belonged to the Early period, three new Vedas were compiled now:

- Samaveda: The Veda of melodies and chants (book of songs).

- Yajurveda: The Veda of sacrificial formulas and rituals (book of rituals).

- Atharvaveda: The Veda of charms and spells to ward off evils and diseases (book of magic/medicine).Additionally, the Brahmanas (prose explanations of rituals) and Aranyakas (forest books) were composed.

Indus Valley Civilization: The Lost Urban Utopia

Quick Comparison Table: Early Vedic vs. Later Vedic Period

| Feature | Early Vedic (1500–1000 BCE) | Later Vedic (1000–600 BCE) |

| Geography | Sapta Sindhu (Punjab) | Gangetic Plain (UP/Bihar) |

| Metal | Copper/Bronze (Ayas) | Iron (Shyama Ayas) |

| Main Wealth | Cattle (Cows) | Land (Territory) |

| Varna System | Flexible (Occupation-based) | Rigid (Birth-based) |

| Status of Women | High (Attended Assemblies) | Declined (Confined to home) |

| Main God | Indra, Agni | Prajapati, Vishnu, Rudra |

| Taxation | Voluntary (Bali) | Mandatory (Bali, Bhaga, Shulka) |

Curious Indian: Fast Facts

- Satyameva Jayate: The national motto of India, “Truth Alone Triumphs,” is taken from the Mundaka Upanishad, which was composed during the late phase of this period.

- Iron Names: In the Vedas, copper is called Lohit Ayas (Red Metal), and iron is called Shyama Ayas or Krishna Ayas (Black Metal).

- Status of Women: The Aitareya Brahmana refers to a daughter as a “source of misery,” a stark contrast to the Early Vedic period where women scholars like Gargi and Maitreyi were respected. However, Gargi famously debated the sage Yajnavalkya in this period, showing that some women still had access to education.

- First Tax Collectors: A new official called the Sangrahitri (treasurer/tax collector) appeared, showing the state now had a regular revenue system.

Conclusion

The Later Vedic Period was the crucible in which the classical Indian civilization was forged. It gave us the caste system, the epic wars (the Mahabharata is believed to be based on the Kuru-Panchala conflict of this time), and the deep philosophy of the Upanishads. It transitioned India from a tribal society to a complex, agrarian state, setting the stage for the rise of the great Mahajanapadas.

Early Vedic Period c. 1500-1000 BCE: The Age of the Rigveda

If you think you have remembered everything about this topic take this QUIZ

What was the main metal used in the Later Vedic Period?

Iron (Shyama Ayas) was the main metal discovered and used.

Which Veda deals with magical charms and spells?

The Atharvaveda deals with charms and spells.

What does the term “Janapada” mean?

It literally means “the foothold of a tribe,” referring to a territorial kingdom where a tribe settled down.

Which deities became important in the Later Vedic Period?

Prajapati (Creator), Vishnu (Preserver), and Rudra (Destroyer) became the most important deities.

What pottery culture is associated with this period?

The Painted Grey Ware (PGW) culture is associated with the Later Vedic period.