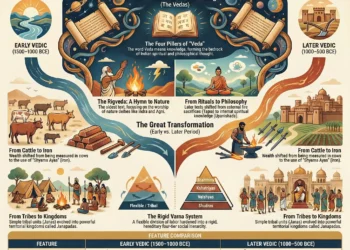

The Decline of the Indus Valley Civilization (also known as the Harappan Civilization) began around 1900 BCE. Unlike the sudden collapse of Pompeii, this was a gradual process of de-urbanization and eastward migration. Large cities like Mohenjo-daro and Harappa were depopulated, their sophisticated drainage systems clogged, and trade with Mesopotamia collapsed. While early colonial historians proposed a violent "Aryan Invasion", modern science points to a "System Collapse" driven by climate change (weakening monsoons), tectonic shifts (drying of the Ghaggar-Hakra/Saraswati river), and economic isolation. The civilization did not vanish; it transitioned into a rural, regional culture known as the Late Harappan Phase.| Feature | Details |

| Start of Decline | c. 1900 BCE |

| Key Period | Late Harappan Phase (c. 1900 – 1300 BCE) |

| Primary Cause | Climate Change (Weakening Monsoon / 4.2k Event) |

| Secondary Causes | Tectonic shifts (River diversion), Flood, Trade collapse |

| Debunked Theory | Violent Aryan Invasion (Mortimer Wheeler’s theory) |

| New Evidence | Rakhigarhi DNA Analysis (2019) |

| Outcome | Shift of population to Gangetic Plains (East) & Gujarat (South) |

| Cultural Shift | Urban -> Rural (De-urbanization) |

What Did “Decline” Look Like?

The decline wasn’t an overnight disappearance. It was a slow decay of civic standards.

- breakdown of Order: In the late phases of Mohenjo-daro, large courtyard houses were partitioned into smaller, cramped quarters.

- Loss of Civic Pride: The famous drainage system was neglected; garbage began to pile up in the streets.

- Disappearance of Script & Seals: The standardized weights, the unicorn seals, and the Indus script vanished, indicating a breakdown in central administration and long-distance trade.

Later Vedic Period c. 1000-600 BCE: The Age of Iron and Kingdoms

Theory 1: The Great Drought (Climate Change)

Modern paleoclimatology provides the strongest evidence. Around 2200 BCE, a global climatic event known as the 4.2 Kiloyear Event caused a mega-drought across Egypt, Mesopotamia, and India.

- Weakening Monsoon: The summer monsoons, which watered the crops, became weak and erratic.

- Impact: Agriculture became unsustainable in the arid zones of Sindh and Rajasthan, forcing people to migrate towards the wetter Gangetic plains in the east.

Theory 2: The Tectonic Shift (The Lost River)

Hydrological studies suggest that the Ghaggar-Hakra River (identified with the Vedic Saraswati), which supported the highest density of Indus settlements, dried up.

- Tectonic Activity: Earthquakes in the Himalayas likely shifted the course of the Yamuna and Sutlej rivers, which fed the Saraswati. Without these tributaries, the mighty river turned into a seasonal stream and eventually dried up.

- The Result: Cities like Kalibangan and Banawali were abandoned as their lifeline vanished.

Theory 3: Floods

While some rivers dried up, the Indus was prone to devastating floods.

- Mohenjo-daro: Excavations show that the city was flooded and rebuilt at least seven times. The constant battle against nature may have exhausted the economic resources of the state.

Rise of Jainism and Buddhism 6th Century BCE

Theory 4: The Aryan Invasion Debate

In the 1950s, archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler famously accused the Vedic god Indra of destroying the Indus cities, citing a group of skeletons found in Mohenjo-daro as evidence of a massacre.

- The Verdict Today: This theory is largely rejected by modern archaeologists. The skeletons show signs of healing (meaning they didn’t die immediately from battle) and belong to different time layers.

- Migration, Not Invasion: Most historians now agree on the Indo-Aryan Migration theory—a gradual influx of pastoralists from Central Asia who arrived after the cities had already declined.

- DNA Evidence: The 2019 Rakhigarhi DNA study showed no Steppe (Aryan) ancestry in the mature Harappan people, proving that the civilization was built by indigenous people before the arrival of the Aryans.

The Aftermath: The Localization Era

The civilization didn’t end; it moved.

- Eastward Shift: Populations migrated to the Ganga-Yamuna doab and Gujarat.

- Ruralization: The great cities dissolved into small agricultural villages. This period is marked by regional cultures like the Cemetery H Culture (Punjab) and Jhukar Culture (Sindh).

Early Vedic Period c. 1500-1000 BCE: The Age of the Rigveda

Quick Comparison Table: Mature vs. Late Harappan Phase

| Feature | Mature Harappan (2600-1900 BCE) | Late Harappan (1900-1300 BCE) |

| Settlement | Urban Cities (Gridded streets) | Rural Villages (Haphazard huts) |

| Trade | International (Mesopotamia) | Local / Regional only |

| Drainage | Sophisticated underground sewers | Open drains / Soak pits |

| Script/Seals | Widely used | Disappeared |

| Pottery | Red and Black Ware (Standardized) | Ochre Colored / Painted Grey Ware |

Curious Indian: Fast Facts

- Mound of the Dead: The name Mohenjo-daro literally means “Mound of the Dead Men” in Sindhi, a name given much later due to the ruins.

- Deforestation: The excessive baking of bricks for construction may have led to massive deforestation, contributing to local climate change.

- The Dholavira Signboard: In its final stages, the giant signboard of Dholavira fell face down, symbolizing the collapse of civic order.

- Survival of Traditions: Though the cities fell, traditions like the “Namaste” greeting, Yoga, and the worship of Pashupati (Shiva) and Mother Goddess survived into modern Hinduism.

Conclusion

The Decline of the Indus Valley Civilization serves as a grim warning from history: even the most advanced societies are vulnerable to climate change. The Harappans didn’t vanish because of a war; they faded because the water ran out. Their legacy, however, survived in the villages of India, forming the bedrock of the culture that would re-emerge in the Second Urbanization.

Indus Valley Civilization: The Lost Urban Utopia

If you think you have remembered everything about this topic take this QUIZ

Results

#1. Unlike the sudden collapse of Pompeii, how do modern historians describe the end of the Indus Valley cities? .

#2. Which climatic event, occurring around 2200 BCE, is cited as a primary driver for the mega-drought that affected the Harappans?

#3. What did the 2019 Rakhigarhi DNA study reveal about the ‘Aryan Invasion’ theory?

#4. In the ‘Late Harappan Phase,’ what happened to the sophisticated gridded streets of the mature cities?

#5. Which of these cultural traditions is believed to have survived the fall of the cities and carried over into modern Hinduism?

#6. What does the name ‘Mohenjo-daro’ literally mean in the Sindhi language?

#7. According to the comparison table, how did ‘Trade’ change during the Late Harappan Phase?

Did the Indus Valley Civilization disappear completely?

No, it de-urbanized. The people migrated to the east and south, transitioning from city life to village life.

Was there an Aryan invasion?

Modern evidence suggests there was no massive violent invasion. The Aryans likely migrated gradually after the cities had already declined due to environmental factors.

What was the main cause of the decline?

Climate change, specifically the weakening of the monsoon and the drying up of the Saraswati (Ghaggar-Hakra) river.

When did the decline start?

The decline began around 1900 BCE.

What is the 4.2 Kiloyear Event?

It was a severe global drought around 2200 BCE that affected civilizations in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Indus Valley.