Uddalaka Aruni was a 7th-century BCE Vedic sage who is widely considered the First Scientist in History for his empirical approach to understanding the universe. Through his teachings in the Chandogya Upanishad, he used logical experiments—such as the Banyan seed and the salt-water tests—to explain the concepts of atomism and the conservation of matter. His philosophy of "Tat Tvam Asi" bridged the gap between physical reality and consciousness, establishing a scientific lineage that influenced Indian thought for millennia.| Attribute | Historical Detail |

| Name | Sage Uddalaka Aruni |

| Era | ~7th Century BCE |

| Primary Source | Chandogya Upanishad |

| Key Discovery | Law of Cause and Effect / Atomism |

| Famous Phrase | “Tat Tvam Asi” (That Thou Art) |

| Historical Title | The First Scientist in History |

The Dawn of Experimental Logic

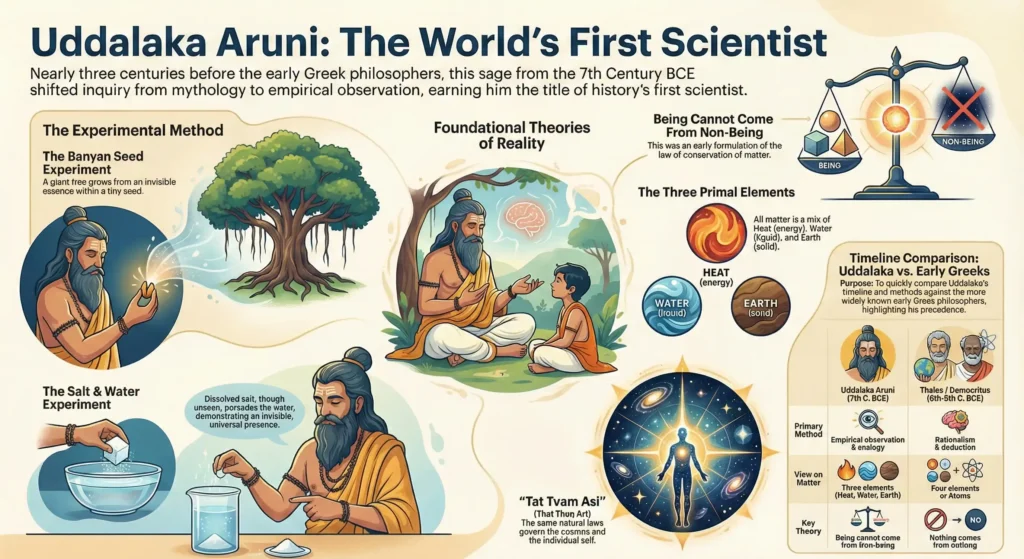

The story of human inquiry often begins with the Greeks, but nearly three centuries before Thales or Democritus, a sage named Uddalaka Aruni was walking the banks of the rivers in North India, asking the same fundamental questions about the nature of reality. He is frequently described by modern historians of science as the First Scientist in History. While his contemporaries were often satisfied with mythological explanations for the world, Uddalaka sought a singular, underlying principle that governed all matter. He wasn’t just a mystic sitting in silence; he was a man of observation, a father who wanted his son to understand the “knowledge by which we hear the unhearable and perceive the unperceivable.”

7 Secrets of Padmanabhaswamy Temple Treasure

Uddalaka lived in a time of profound intellectual transition. The Vedic era was evolving, and the focus was shifting from external rituals to internal discovery. However, Uddalaka’s approach was uniquely empirical. He believed that the universe followed a set of laws and that these laws could be understood by studying the physical world. This shift from “who created the world” to “what is the world made of” is precisely why he holds the title of the world’s first true scientist.

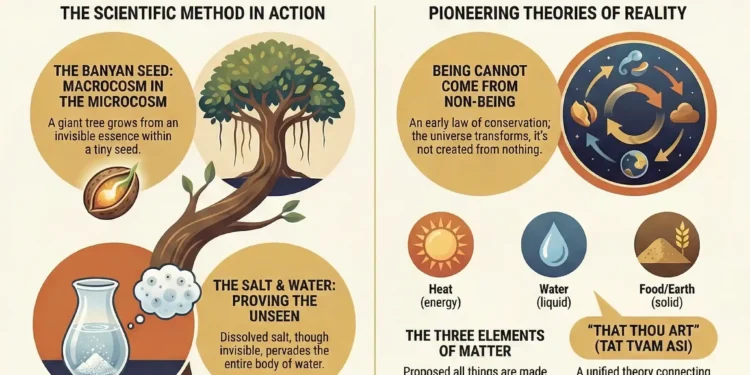

The Mystery of the Banyan Seed

One of the most famous anecdotes involving the First Scientist in History is his teaching session with his son, Shvetaketu. Shvetaketu had returned from twelve years of formal study, perhaps a bit arrogant about his book learning. To humble and enlighten him, Uddalaka asked him to bring a fruit from a nearby Nyagrodha (Banyan) tree. “Break it,” Uddalaka commanded. “What do you see?” Shvetaketu replied that he saw tiny seeds. “Break one of those seeds,” the father said. “Now, what do you see?” Shvetaketu replied, “Nothing at all, father.”

Uddalaka used this “nothingness” to explain a profound physical truth. He argued that the giant Banyan tree, with its massive trunk and sprawling branches, emerged from that invisible essence within the seed. This was an early form of biological and physical deduction. He was demonstrating that the macrocosm (the tree) is contained within the microcosm (the seed’s essence). This wasn’t magic; it was an early observation of the potential energy and biological blueprints that govern life.

7 Untold Stories of Battle of Asal Uttar 1965 Victory

Pioneering Ancient Indian Physics

Uddalaka’s theories on matter were revolutionary for the 7th Century BCE. He proposed that the universe began as “Sat”—Being or Existence. He argued against the idea that the world came from nothing, famously asking, “How could Being be produced from Non-being?” This is one of the earliest recorded statements of the law of conservation of matter and energy. In his view, the universe was a process of constant transformation rather than creation ex nihilo.

He went further into ancient Indian physics by suggesting that all physical objects are made of three essential elements: heat (Tejas), water (Ap), and food/earth (Anna). While this may sound simple today, it was a sophisticated attempt to categorize the states of matter—energy, liquid, and solid. He believed that by understanding the proportions of these three elements, one could understand the composition of any object in the physical world. This systematic categorization is the very heartbeat of the scientific method.

Tat Tvam Asi: The Unity of All Things

While he explored the physical, Uddalaka never lost sight of the observer. His most famous teaching, Tat Tvam Asi meaning “That Thou Art,” is the ultimate bridge between physics and consciousness. After demonstrating the physical essence of the Banyan seed or the salt in water, he would tell his son: “That subtle essence which is the self of all this world, that is the Truth, that is the Self, and That, Shvetaketu, art Thou.”

This was an early attempt at a Unified Field Theory. Uddalaka was suggesting that the same laws that govern the stars and the seeds also govern the human mind and soul. By realizing that we are made of the same “essence” as the rest of the universe, he was encouraging a sense of universal responsibility and interconnectedness. It was a spiritual conclusion reached through physical observation—a hallmark of the Chandogya Upanishad teachings.

6 Unfoldings in the Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar Biography

The Salt and the Water Experiment

To further prove his point to his skeptical son, the First Scientist in History performed another experiment. He asked Shvetaketu to place a lump of salt in a bowl of water overnight. The next morning, he asked the boy to retrieve the salt. Of course, the salt had dissolved. Uddalaka then asked his son to sip the water from the top, the middle, and the bottom. Shvetaketu reported that it was salty everywhere.

Uddalaka explained that even though the salt could not be seen or grasped, it pervaded the entire body of water. This was an early lesson in atomic theory and the nature of solutions. He used this physical evidence to explain that the “Self” or the “Essence” of the universe is similarly invisible but pervades everything. This use of repeatable, observable experiments to explain abstract concepts is what truly separates Uddalaka Aruni from the poets and mythmakers of his age.

The Legacy of the Shravasti Sage’s Contemporary

Uddalaka Aruni’s influence on Indian thought cannot be overstated. He was the teacher of the great Yajnavalkya, another titan of Vedic wisdom. His lineage of thought moved toward a rational, almost atheistic exploration of the world that eventually paved the way for the Samkhya and Vaisheshika schools of philosophy—the latter of which would develop a full-blown atomic theory.

His Uddalaka Aruni philosophy traveled through the centuries, influencing the way Indians approached medicine, metallurgy, and mathematics. He taught that the mind itself was a product of the food we eat, suggesting a biological basis for consciousness long before modern neuroscience. By treating the mind and body as parts of a physical system, he removed the “supernatural” veil from human existence and replaced it with a quest for natural laws.

8 Defining Chapters in the Vikram Sarabhai Biography

Quick Comparison: Uddalaka vs. Early Greek Philosophers

| Feature | Uddalaka Aruni (7th Century BCE) | Thales / Democritus (6th-5th Century BCE) |

| Primary Method | Empirical observation and analogy | Rationalism and deduction |

| View on Matter | Three elements (Heat, Water, Earth) | Four elements or Atoms (Atomos) |

| Key Theory | Being cannot come from Non-being | Nothing comes from nothing |

| Experiments | Salt dissolution, seed dissection | Observation of shadows and water |

| Goal | Unity of Self and Universe | Understanding the “Arche” (origin) |

Curious Indian: Fast Facts

- Uddalaka Aruni is the most frequently mentioned sage in the Upanishads.

- He is credited with the world’s first documented “thought experiments.”

- His name “Aruni” comes from his father, Sage Aruni, but he became more famous than his teacher.

- He proposed that the mind is made of the “subtlest part of food.”

- The phrase “Tat Tvam Asi” is considered one of the four Mahavakyas (Great Utterances) of Indian philosophy.

Conclusion

Uddalaka Aruni proves that the quest for scientific truth is an ancient human instinct that transcends geography. As the First Scientist in History, he taught us that to understand the infinite, we must first learn to look closely at the small. His legacy at curiousindian.in serves as a reminder that the “scientific temper” isn’t a modern Western invention, but a flame that has been burning in the Indian heart for over 2,700 years. By looking at the Banyan seed through his eyes, we find not just a tree, but the entire universe.

Dr. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam: (1931-2015)

If you think you have remembered everything about this topic take this QUIZ

Results

#1. Who is described in the text as the “First Scientist in History,” living nearly three centuries before the Greek philosophers?

#2. What profound physical truth did Uddalaka demonstrate to his son using the “nothingness” inside a Banyan seed?

#3. Which question did Uddalaka famously ask to argue against the idea that the world was created from nothing?

#4. According to Uddalaka, what three essential elements constitute all physical objects?

#5. What was the purpose of the experiment where Shvetaketu was asked to find dissolved salt in water?

#6. What is the meaning of the famous phrase “Tat Tvam Asi” taught by Uddalaka?

#7. Uddalaka proposed that the human mind is formed from which biological source?

#8. Unlike the rationalism and deduction of early Greek philosophers like Thales, what was Uddalaka Aruni’s primary method?

Why is Uddalaka Aruni called the First Scientist in History?

He is called the first scientist because he moved away from mythological explanations and used observation, logic, and experiments to explain the nature of matter and existence.

What is the meaning of “Tat Tvam Asi”?

It means “That Thou Art.” It is a teaching that suggests the individual self is identical to the ultimate, subtle essence of the universe.

Which Upanishad contains his teachings?

Most of his famous teachings, including the dialogue with his son Shvetaketu, are found in the Chandogya Upanishad.

Did Uddalaka Aruni believe in atoms?

While the word “atom” is Greek, Uddalaka described the “subtle essence” of matter that is invisible to the eye but forms the basis of all physical objects, which is a precursor to atomic theory.

What was his view on the mind?

He had a surprisingly physical view of the mind, teaching that it was formed from the subtle essence of the food we consume, effectively linking biology with psychology.