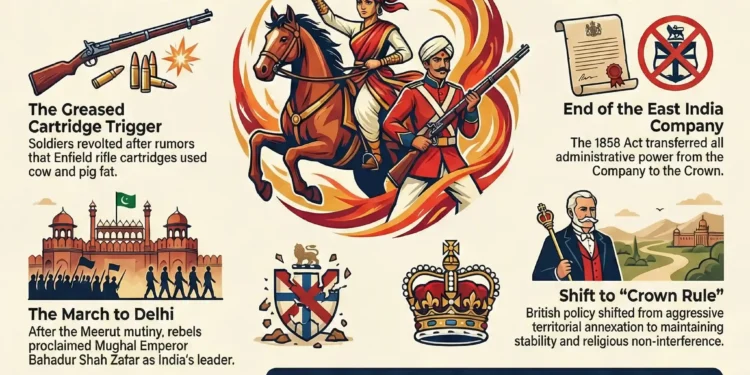

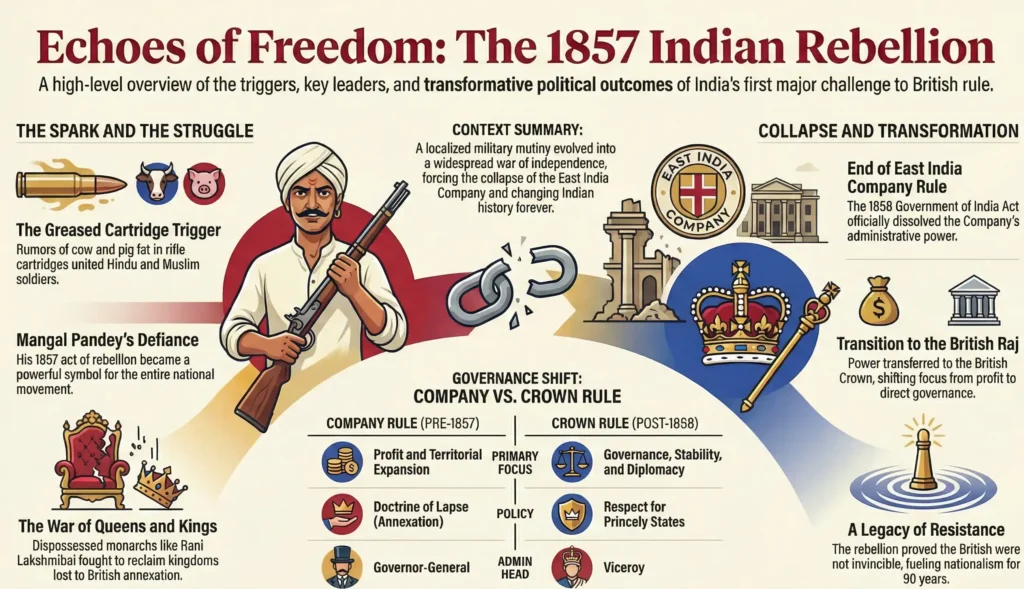

The Indian Rebellion of 1857, widely regarded as India's First War of Independence, began as a mutiny of sepoys in the British East India Company's army on May 10, 1857, in Meerut. Triggered by the introduction of the Enfield rifle (which used cartridges rumored to be greased with cow and pig fat), the revolt quickly spread to Delhi, Kanpur, Lucknow, and Jhansi. It united soldiers, peasants, and disgruntled monarchs like Rani Lakshmibai, Nana Sahib, and the last Mughal Emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar. Although the rebellion was brutally suppressed by 1858, it led to the dissolution of the East India Company and the establishment of direct rule by the British Crown (the British Raj).| Feature | Details |

| Start Date | May 10, 1857 |

| Start Location | Meerut Cantonment |

| Key Trigger | Enfield Rifle (Greased Cartridges) |

| Symbolic Leader | Bahadur Shah Zafar II (Mughal Emperor) |

| Key Leaders | Rani Lakshmibai, Nana Sahib, Tatya Tope, Kunwar Singh |

| Outcome | British Victory; End of Company Rule |

| Consequence | Government of India Act 1858 (Crown Rule) |

| Casualties | Est. 100,000+ Indians (Soldiers & Civilians) |

The Spark: Mangal Pandey and the Cartridges

The immediate cause of the rebellion was the introduction of the Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle. To load it, soldiers had to bite off the end of a paper cartridge. Rumors spread that the grease used on these cartridges was a mixture of cow fat (sacred to Hindus) and pig fat (forbidden to Muslims).

On March 29, 1857, at Barrackpore, a young sepoy named Mangal Pandey refused to use the cartridges and fired at his British officers. He was hanged on April 8, but his act of defiance electrified the army. “Mangal Pandey” became a synonym for a rebel.

The Meerut Mutiny and the March to Delhi

The real explosion happened on May 10, 1857, in Meerut. After 85 sepoys were court-martialed for refusing the cartridges, their comrades broke open the jails, killed their European officers, and marched to Delhi.

On reaching Delhi the next morning, they proclaimed the 81-year-old Mughal Emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, as the Shahenshah-e-Hindustan (Emperor of India). For a few months, Delhi was once again the capital of a free India.

The Final Walk: The Conspiracy Behind Mahatma Gandhi’s Death

The War of Queens and Kings

The rebellion was not just a soldier’s mutiny; it was a desperate last stand by the old Indian aristocracy against British annexation policies like the Doctrine of Lapse.

- Jhansi: Rani Lakshmibai, the warrior queen, refused to surrender her kingdom after her adopted son was denied the throne. She died fighting on the battlefield in Gwalior, famously described by her British enemy, Hugh Rose, as “the only man among the rebels.”

- Kanpur: Nana Sahib (the adopted son of the exiled Peshwa) led the revolt here, expelling the British garrison.

- Awadh (Lucknow): Begum Hazrat Mahal led the resistance in Lucknow, ruling in the name of her minor son after her husband was exiled.

- Bihar: Kunwar Singh, an 80-year-old zamindar from Jagdishpur, fought a guerrilla war against the British, proving age was no barrier to patriotism.

The Brutal Suppression

The British response was savage. They did not just want to defeat the rebels; they wanted to terrorize the population. Villages suspected of supporting rebels were burned to the ground. In Delhi, after recapturing the city in September 1857, the British massacred thousands. Bahadur Shah Zafar was arrested, his sons were shot in cold blood by Major Hodson, and he was exiled to Rangoon (Burma), where he died in anonymity.

Jallianwala Bagh Massacre 1919: Inside the Tragedy That Ignited a Revolution

Why Did the Rebellion Fail?

Despite the heroism, the rebellion failed for several reasons:

- Lack of Unity: It was restricted largely to North and Central India. The South, Bengal, and Punjab remained mostly quiet or loyal to the British.

- No Common Goal: While everyone hated the British, they had different visions for the future—some wanted to restore the Mughals, others the Marathas.

- Superior British Resources: The British had better telegraph communication, modern weapons, and experienced generals.

The Aftermath: A New Era

The rebellion ended the rule of the East India Company. The British Parliament passed the Government of India Act 1858, transferring power to the British Crown. Queen Victoria issued a proclamation promising religious tolerance and no further territorial annexation, marking the beginning of the British Raj.

Indian National Congress Founded 1885: The Birth of Indian Nationalism

Quick Comparison Table: Company Rule vs. Crown Rule

| Feature | Company Rule (Pre-1857) | Crown Rule (Post-1858) |

| Focus | Profit & Expansion | Governance & Stability |

| Policy | Doctrine of Lapse (Annexation) | Respect for Princely States |

| Army | High ratio of Indian soldiers | Increased European troops; Artillery under British control |

| Religion | Active Missionary work | Official Non-Interference |

| Admin Head | Governor-General | Viceroy |

Curious Indian: Fast Facts

- The Chapati Movement: Just before the revolt, mysterious chapatis (flatbreads) were passed from village to village across North India. To this day, historians debate whether it was a secret code for the uprising or a superstitious ritual against cholera.

- The “Devil’s Wind”: The British retaliation was so fierce that locals called it the Shaitan ki Hawa (Devil’s Wind). Rebels were famously “blown from cannons”—tied to the mouth of a cannon and blasted apart.

- Tatya Tope: The master of guerrilla warfare, Tatya Tope, evaded the British for nearly a year in the jungles of central India before being betrayed and hanged in 1859.

- Karl Marx on 1857: Interestingly, Karl Marx wrote articles for the New York Daily Tribune supporting the rebellion, calling it a “national revolt” rather than a mere military mutiny.

Conclusion

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a glorious failure. It failed to drive the British out, but it succeeded in creating a memory of resistance. The stories of Lakshmibai and Mangal Pandey became the folklore that fueled the freedom struggle 90 years later. It proved that the British Empire was not invincible and that India could unite against a common enemy.

Establishment of the British Raj 1858: The Dawn of Imperial India

If you think you have remembered everything about this topic take this QUIZ

Results

#1. What was the immediate cause that triggered the Revolt of 1857?

#2. Who was the first martyr of the revolt, hanged for defying British officers at Barrackpore?

#3. The revolt officially began on May 10, 1857, in which cantonment town?

#4. Who was proclaimed the “Shahenshah-e-Hindustan” (Emperor of India) by the rebels?

#5. Which 80-year-old leader led the rebellion in Bihar?

#6. What was the major political consequence of the revolt’s suppression in 1858?

#7. Just before the revolt, which mysterious food item was passed from village to village?

Who was the first martyr of the 1857 Revolt?

Mangal Pandey is considered the first martyr, executed on April 8, 1857, at Barrackpore.

Who led the revolt in Jhansi?

Rani Lakshmibai led the revolt in Jhansi against the Doctrine of Lapse.

What was the immediate cause of the 1857 Revolt?

The immediate cause was the introduction of Enfield rifle cartridges rumored to be greased with cow and pig fat.

Who was the Governor-General during the 1857 Revolt?

Lord Canning was the Governor-General during the revolt and became the first Viceroy after it.

What happened to the Mughal Empire after 1857?

The Mughal Empire was formally abolished. The last emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, was exiled to Rangoon, Burma, where he died in 1862.