Introduction

South India’s Dravidian temple architecture is a millennium-long conversation between faith, engineering, sculpture, and civic life. Emerging decisively by the late 7th century and reaching monumental maturity by the 16th century, this style is recognizable by its pyramidal vimana above the sanctum, colossal gopurams (gateway towers), enclosed prakara walls, and sacred tanks. Unlike many northern temples raised on lofty plinths, Dravidian temples often grow outward as vast complexes—ritual centers that also managed land, labor, learning, and local economies. This article traces that evolution from Pallava experimentation to Chola monumentality and Vijayanagara’s temple-towns, highlighting form, function, and legacy.

Core Features of the Dravidian Idiom

Vimana: Stepped, pyramidal superstructure above the garbhagriha, crowned by a small dome-like stupika/shikhara (distinct from the curvilinear northern shikhara).

Gopuram: Multi-storeyed, sculpted entrance towers on enclosure walls; in later periods, these dominate the skyline and become the complex’s visual signature.

Enclosures and processions: Concentric prakara walls with axial gateways; circumambulatory routes for daily and festival processions.

Temple tank (pushkarini): Integral for ritual purity and water management; anchors community life.

Sculptural program: Dvarapalas, yakshas, deity panels, and puranic narratives; inscriptions recording grants, endowments, and administration.

Institutional role: From the 8th–12th centuries, temples became administrative hubs managing land, festivals, artisans, and education.

Canonical Forms and Subdivisions

Traditional Dravida massing uses square and oblong modules (e.g., kuta, shala) stepped in tiers (talas) toward the crowning element.

Storey-wise articulation features projecting cornices (kapota), miniature shrine motifs (kuta-shala) on tier faces, and rhythmic recesses that break mass into readable layers.

Pallava Foundations (c. 600–900 CE): From Rock-Cut to Structural

Mahendravarman I (c. 600–625): Early rock-cut caves/mandapas (e.g., Mahendravadi, Tiruchirappalli) test excavated spatial grammars.

Narasimhavarman I “Mamalla” (c. 625–667): Monolithic rathas and sculptural mandapas at Mamallapuram (Pancha Rathas) showcase proto-structural imagination in single-rock models.

Narasimhavarman II “Rajasimha” (c. 700–728): Transition to full structural stone. Shore Temple (Mahabalipuram) faces the sea with an unusual triadic scheme (two Shiva shrines, one Vishnu in Anantashayana), likely reflecting additive phases. Kailasanatha Temple (Kanchipuram) refines Dravida form with compact vimana tiers, crisp molding profiles, and emphatic door guardians.

Nandivarman line (c. 800–900): Continues smaller structural shrines; early gopuram prototypes and enclosure logic consolidate.

Key takeaways:

Rock-cut experimentation led to confident structural masonry.

Early vimanas emphasize compact verticals; enclosures and water elements appear.

Iconographic range is primarily Shaiva with resilient Vaishnava survivals.

Chola Zenith (c. 875–1175 CE): Monumentality and Management

Royal patronage scales up every dimension—mass, sculpture, murals, inscriptions, and administration.

Brihadeeswara, Thanjavur (c. 1010, Raja Raja I): A soaring ~70 m pyramidal vimana topped by a monolithic capstone; axial planning, two imposing gopurams, and extensive murals. Part of the “Great Living Chola Temples.”

Gangaikondacholapuram and Airavatesvara (Darasuram): Further advances in sculptural finesse, mandapa articulation, and bronze icon traditions (processional utsava murtis).

Inscriptions detail land grants, guilds, and festival logistics—temples operate as civic engines.

Key takeaways:

Precision geometry and rhythmic tiering define Chola vimanas.

Integrated gopuram–vimana compositions become standard.

Temples function as cultural capitals—administrative, ritual, and artistic.

Regional Refinements and Hybrids

Chalukya-Hoysala line (esp. south Karnataka) enriches ornament and plan innovation. Hoysala temples (Belur, Halebid) emphasize star-plans, lathe-turned pillars, and soapstone intricacy—a parallel flowering adjacent to core Dravida grammar.

Pandya and Nayaka traditions expand pillared halls, processional corridors, and sculptural abundance across Tamil country.

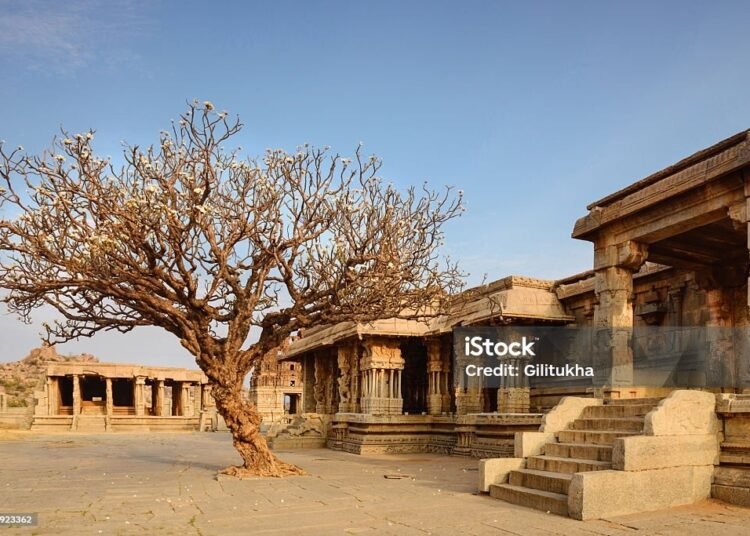

Vijayanagara Transformations (c. 14th–16th centuries): Temple-Towns and Towered Gates

The temple complex expands into an urban matrix; gopurams become the dominant vertical markers, sheathed in stuccoed tiers and visible for miles.

Architectural signatures include long pillared mahamandapas, kalyana mandapas (marriage halls), yali (mythic) composite pillars, and large water tanks.

Exemplary complexes include Hampi (Virupaksha), Madurai (Meenakshi–Sundareshwar), Srirangam (Ranganathaswamy), and Kanchipuram clusters—each blending sacred geography with civic life.

Key takeaways:

Emphasis shifts from vimana height to gopuram dominance.

Concentric enclosures structure movement and ritual sequencing.

Complexes operate as temple-towns—economically, ritually, and socially integrated.

Dravida vs. Nagara: A Quick Contrast

Plinth vs. enclosure: Nagara often favors raised platforms and a spire-centric silhouette; Dravida emphasizes enclosed compounds with axial gates and tanks.

Superstructure: Curvilinear shikhara (Nagara) contrasts with stepped pyramidal vimana crowned by a small domed finial (Dravida).

Thresholds: Towering gopurams are quintessentially Dravidian, framing sacred processions and announcing the complex from a distance.

How to Read a Dravidian Temple On-Site

Approach and axis: Trace the line from gopuram to sanctum; observe how gateways compress and release space.

Vimana anatomy: Count talas; note cornices, miniature aedicules (kuta, shala), and the crowning stupika.

Iconography: Identify dvarapalas, deity enshrined, narrative panels, and inscription slabs; connect scenes to Puranic cycles.

Waterworks: Locate the tank; consider hydrology and festival usage.

Material and technique: Granite/basalt masonry, joinery, polishing; later stucco on gopurams; painted cycles where preserved.

Practical Takeaways for Learners and Travelers

Trace the chronology: Pallava (rock-cut to structural), Chola (monumental vimana), Vijayanagara (gopuram-dominant temple-towns).

Study circuits:

Kanchipuram: Kailasanatha for Pallava finesse; later shrines for continuity.

Thanjavur–Gangaikondacholapuram–Darasuram: Chola scale, murals, inscriptions, bronzes.

Madurai–Srirangam–Kanchipuram–Hampi: Vijayanagara gopurams, pillared halls, urban sacred planning.

Etiquette and preservation: Dress modestly; respect photography restrictions (especially murals and inner sanctums); support conservation by following guided routes.

Conclusion

From Pallava rock-cut prototypes to Chola mathematical monumentality and Vijayanagara’s gopuram-studded temple-towns, Dravidian architecture narrates South India’s synthesis of devotion, design, and governance. These complexes are not static ruins but living systems—where processions, water, sculpture, music, and management cohere. To walk their axes is to witness an unbroken lineage of sacred urbanism: the temple as both sanctum and city.