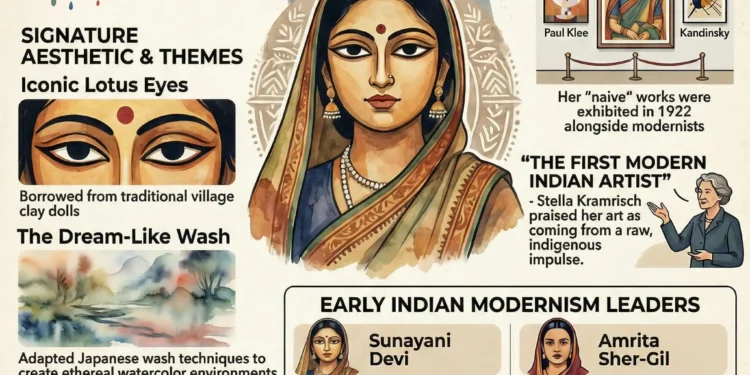

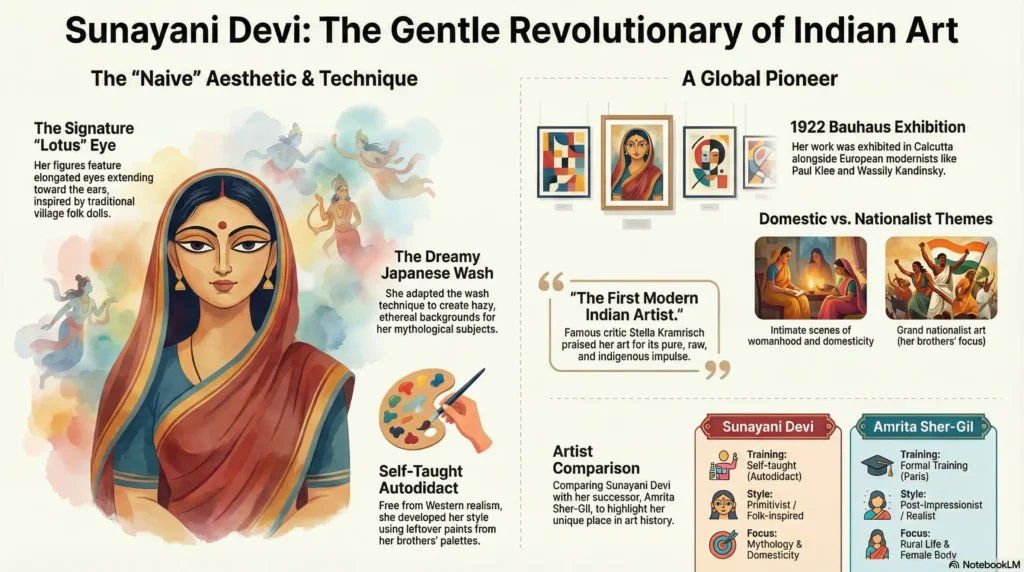

Sunayani Devi (1875–1962) was a pioneering Indian artist and a member of the illustrious Tagore family. The younger sister of Abanindranath and Gaganendranath Tagore, she is often cited as the first modern woman painter of India. Unlike her brothers, she received no formal training. She began painting at the age of 30, developing a unique, self-taught style that critics later termed "Naive" or "Primitivist." Drawing inspiration from Kalighat Pat paintings and Indian folk dolls, her works are characterized by elongated eyes, soft wash techniques, and mythological themes centered on women. Despite being overshadowed by her male relatives, her work was highly acclaimed by art critics like Stella Kramrisch and was even exhibited by the Bauhaus in 1922.| Feature | Details |

| Born | 18 June 1875 |

| Died | 23 February 1962 |

| Family | Tagore Family (Sister of Abanindranath & Gaganendranath) |

| Art Style | Primitivist / Naive Art / Bengal School |

| Key Influences | Kalighat Pats, Indian Folk Dolls, Pata Chitra |

| Medium | Watercolor, Tempera, Wash Technique |

| Key Works | Milk Maids, Sadhika, Ardhanarisvara, Yashoda and Krishna |

| Exhibitions | Indian Society of Oriental Art (Calcutta, London, USA), Bauhaus (1922) |

| Famous Critic | Stella Kramrisch (called her the “first modern Indian artist”) |

The Shadow of Genius

Born into the Jorasanko Thakurbari, the epicenter of Bengal’s cultural renaissance, Sunayani grew up surrounded by art and literature. She was the younger sister of the masters Abanindranath Tagore (founder of the Bengal School) and Gaganendranath Tagore (cubist painter). While her brothers were formally trained and deeply involved in the Swadeshi art movement, Sunayani was raised in the traditional Andarmahal (inner quarters) of the household. She was married at the age of 11 to Rajanimohan Chattopadhyaya.

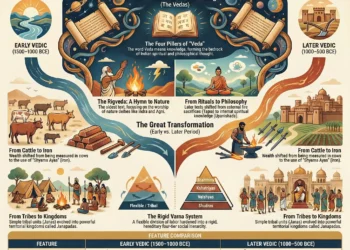

Vedic Period: From Nomadic Hymns to Iron Age Kingdoms

The Accidental Artist

Sunayani’s entry into art was serendipitous. She reportedly started painting around the age of 30, not out of ambition, but out of curiosity. Watching her brothers work, she began experimenting with the leftover colors on their palettes. Unlike the rigid academic training of the time, her lack of schooling became her greatest asset. It allowed her to develop a style that was entirely her own—free from the “burden” of Western realism or the strict rules of Indian classical art.

The “Primitive” Style: A Folk Modernist

Sunayani Devi’s style is often described as Primitivist. This does not mean “backward,” but rather a deliberate return to simplicity and innocence.

- Influences: She drew heavy inspiration from the Kalighat Pata paintings (bazaar art of Calcutta) and the clay dolls found in village fairs. * Technique: She used the Japanese Wash technique (popularized by her brother Abanindranath) but adapted it. She would dip her paper in water and apply hazy, dream-like colors.

- The Eyes: The most striking feature of her paintings is the eyes. Her figures have elongated, lotus-shaped eyes that extend almost to the ears—a trait borrowed from traditional Indian sculpture and folk art.

8 Defining Chapters in the Vikram Sarabhai Biography

Themes: A Woman’s World

While the male artists of the Bengal School often painted grand historical or nationalist themes, Sunayani focused on the intimate and the domestic.

- Mythology: She painted scenes from the epics, focusing on female figures like Radha, Yashoda, and the Gopis. Her Yashoda and Krishna series is celebrated for its tender depiction of motherhood.

- Domesticity: Her works often featured women engaged in daily rituals, blending the divine with the mundane.

- Simplicity: There were no elaborate backgrounds or complex perspectives. Her figures floated in a soft, ethereal space.

Recognition and The Bauhaus Connection

Despite her “amateur” status, the art world took notice.

- Stella Kramrisch, the famous Austrian art historian, was a huge admirer. She wrote in 1925 that Sunayani’s art was “pure and simple” and that she was, in a sense, more “modern” than her brothers because her art came from a raw, indigenous impulse.

- The Bauhaus: In 1922, an exhibition of artists from the Bengal School was held in Calcutta, organized with the Bauhaus movement of Germany. Sunayani’s works were displayed alongside European modernists like Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky, highlighting the global appeal of her “naive” aesthetic.

1971 Nagarwala Case: India’s Great Bank Heist Mystery

Quick Comparison Table: Sunayani Devi vs. Amrita Sher-Gil

| Feature | Sunayani Devi | Amrita Sher-Gil |

| Era | Early 20th Century (Bengal School) | Mid 20th Century (Modernism) |

| Training | Self-taught (Autodidact) | Formal Training (Paris, Ecole des Beaux-Arts) |

| Style | Primitivist, Folk-inspired, Wash | Post-Impressionist, Realist |

| Medium | Watercolor / Tempera | Oil on Canvas |

| Focus | Mythology, Domesticity, Innocence | Rural Life, Poverty, Female Body |

| Legacy | The “Gentle Woman” of Art | The “Frida Kahlo” of India |

Curious Indian: Fast Facts

- The Secret Painter: She often painted in secret or during the quiet afternoon hours when the household chores were done, hiding her work from the critical eyes of the male members initially.

- Grandmother’s Model: She sometimes modeled her figures on the maids and women of the Tagore household, capturing their simple sarees and jewelry.

- Descendant of Reformers: Her husband, Rajanimohan, was the grandson of the great social reformer Raja Ram Mohan Roy.

- Forgotten Legacy: By the 1940s, as modernism shifted towards the bold oils of the Progressives (like Souza and Husain), Sunayani’s delicate watercolours fell out of fashion, and she largely faded into obscurity.

Conclusion

Sunayani Devi proved that art does not require a degree; it requires a soul. In a time when Indian art was trying to define itself against British academic realism, she bypassed the debate entirely by looking inward—at the dolls, the myths, and the women of Bengal. She remains a crucial link between traditional Indian folk art and modern expressionism, a “gentle revolutionary” who painted her own world while the world outside changed.

If you think you have remembered everything about this topic take this QUIZ

Results

#1. To which illustrious family did Sunayani Devi belong?

#2. At what age did Sunayani Devi begin her serendipitous journey into painting?

#3. What term did art critics later use to describe Sunayani Devi’s unique, self-taught style?

#4. Sunayani Devi drew heavy inspiration from which local bazaar art form of Calcutta?

#5. What is the most striking and characteristic physical feature of the figures in her paintings?

#6. Which famous Austrian art historian was a huge admirer and called her the “first modern Indian artist”?

#7. In 1922, Sunayani Devi’s works were exhibited in Calcutta alongside European modernists from which famous movement?

#8. According to the text, who was the famous grandfather of Sunayani Devi’s husband, Rajanimohan?

Who was Sunayani Devi?

Sunayani Devi was a self-taught Indian artist from the Tagore family and one of the first female modernists of the Bengal School of Art.

What is unique about her painting style?

Her style is characterized by the “Wash technique,” elongated lotus-shaped eyes, and a “Naive” or “Primitivist” approach inspired by Kalighat folk art.

Did she receive formal art training?

No, unlike her brothers Abanindranath and Gaganendranath, she was entirely self-taught.

Which famous art critic praised her work?

Stella Kramrisch, a renowned art historian, praised her work for its purity and indigenous roots.

What are her most famous themes?

She primarily painted scenes from Hindu mythology (Krishna, Radha, Gopis) and domestic female life.