Introduction

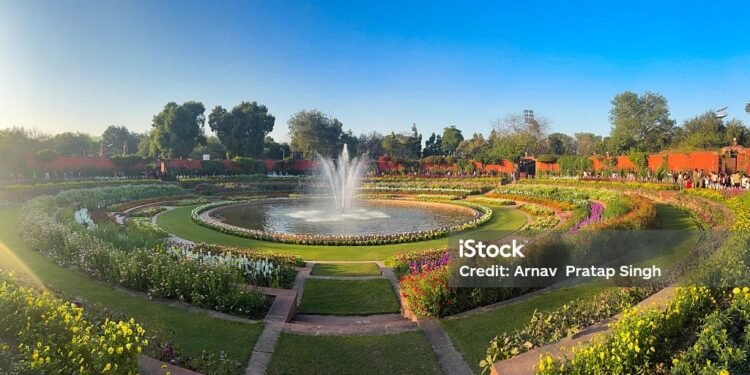

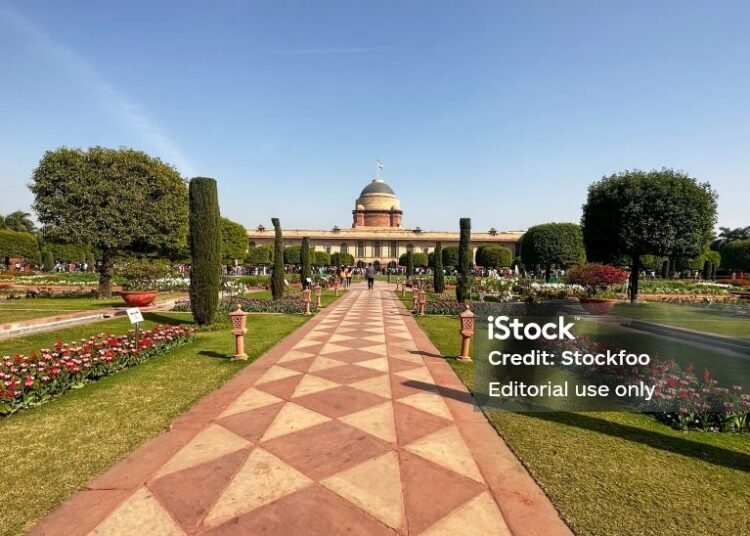

The Mughal charbagh is a Persianate garden ideal translated into the Indian landscape: a geometrically enclosed, water-laced quadrilateral evoking the Quranic paradise where “rivers flow beneath.” At Humayun’s Tomb in Delhi, this vision unfurls across roughly 30 acres, with the garden encircling the tomb on all four sides. Laid out as four equal quadrants bisected by axial walkways and water channels, the plan choreographs movement, sightlines, breeze, and sound—turning architecture and landscape into a unified spiritual experience. The charbagh would become a defining hallmark of Mughal aesthetics, influencing gardens and funerary complexes for centuries.

The Charbagh Concept: Form, Meaning, Experience

Quadripartite plan: A square or rectangle is divided into four equal squares by two intersecting axes—khiyaban (paved walkways) and canals—creating a cruciform scheme.

Rivers of paradise: The central channels symbolize the four rivers of jannat, reinforcing the garden’s eschatological reading as a terrestrial paradise.

Enclosure and threshold: High perimeter walls and controlled gateways frame a sanctified interior, heightening the transition from city to oasis.

Architecture as anchor: The tomb (or pavilion) occupies the compositional center, aligning water, walkways, and prospect views to a spiritual focal point.

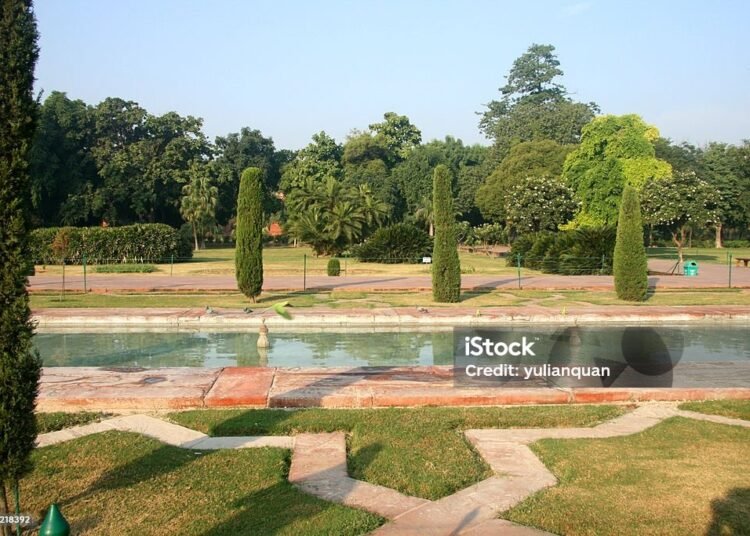

Sensory orchestration: Running water, shaded paths, and vegetation moderate heat and dust while offering auditory calm and visual symmetry.

Humayun’s Tomb, Delhi: The First Great Mughal Garden-Tomb

Scale and setting: A vast charbagh envelops the red sandstone mausoleum, an early and influential garden-tomb on the subcontinent.

Axial order: Two orthogonal channels and paths divide the precinct into four, then into smaller modules (commonly read as 36 sub-squares), enabling rhythmic pacing and layered vistas.

Water choreography: Channels “disappear” beneath the platform and re-emerge in continuity, dramatizing the idea of life-giving rivers under the house of the eternal.

Controlled access: The complex is enclosed by towering rubble walls; principal entry was historically via the south gate (now closed), with the west gate in current use. A baradari (12-doored pavilion) on the east wall and a hammam (bath) on the north wall complete the ensemble logic.

Material and form: The mausoleum’s red sandstone mass and pale dome contrast against the green of the quadrants—an intentional coloristic balance of earth, sky, and garden.

Elements of the Mughal Charbagh

Khiyaban (walkways): Broad, tree-lined paths guiding processions and pilgrim routes, reinforcing orthogonal clarity.

Nahr (water channels) and hauz (tanks): Linear rills and square basins articulate nodes and crossings; reflections double the monument and sky.

Baradari: Open pavilions with multiple doorways exploit cross-breezes for rest, reception, and ceremony.

Hammam: Bath structures underscore the cleansing, paradisal ethos of water within the precinct.

Gates and sequence: Major and minor gateways calibrate entry, orientation, and the unfolding of perspective toward the tomb.

Planting palette: Shade trees, flowering shrubs, and fruit-bearing species provide fragrance, color, and sustenance, aligning utility with metaphysics.

Geometry and Cosmology: Why the Plan Matters

Mandala logic in Islamic-Persian idiom: The equal partition of space projects order, balance, and divine justice; the center manifests sovereignty and spiritual stillness.

Processional movement: Visitors traverse from threshold to center along cardinal axes, passing water crossings that punctuate pace and attention.

Vertical symbolism: The dome—read as the vault of heaven—rises from a plinth amid the “garden of paradise,” with channels metaphorically flowing beneath.

Hydrology and Climate Intelligence

Gravity-fed networks: Historical channels, step gradients, and subterranean conduits moved water across axes and basins, sustaining both spectacle and irrigation.

Microclimate: Water, shade, and enclosure mitigate Delhi’s heat and dust, transforming the precinct into a cool, habitable refuge.

Maintenance as design: Regular desilting, masonry upkeep, and planting cycles were intrinsic to performance and meaning.

Charbagh Beyond Delhi: A Lasting Mughal Signature

Typology adoption: The charbagh schema influenced later Mughal funerary and pleasure gardens across North India.

Adaptation to site: While cardinal geometry remained consistent, designers tailored enclosure, water supply, and planting to rivers, terraces, and urban edges.

Garden as ideology: The layout asserts a vision of just kingship, celestial order, and aesthetic restraint—an earthly paradise curated by human craft under divine law.

Reading the Garden On-Site: A Short Guide

Start at the gate: Note the compression of space and view-framing as the garden reveals itself.

Follow the axes: Walk the khiyabans to understand proportion, scale shifts, and how the monument commands the crossings.

Watch the water: Trace channels under platforms; observe reflections and sound modulation at junction basins.

Seek the nodes: Pause at the baradari and water pavilions to experience wind, shade, and sightline alignments.

Circle the center: Move around the tomb to perceive how each quadrant repeats order with small variations in planting and paths.

Design Takeaways

Unity of parts: Architecture, waterworks, horticulture, and walls act as one system—remove any, and the meaning weakens.

Axial clarity: Strong cardinal alignments create legibility and spiritual directionality.

Sensory balance: Mughal gardens succeed because geometry meets microclimate, ritual meets repose, and symbolism meets utility.

Taj Mahal complex

Conclusion

The charbagh makes paradise legible on earth. At Humayun’s Tomb, water channels trace the promise of rivers beneath, orthogonal paths embody justice and order, and the tomb, at perfect center, reconciles earth and sky. This is landscape as theology, architecture as cosmogram—a timeless Mughal synthesis where geometry, climate, and devotion conjoin.