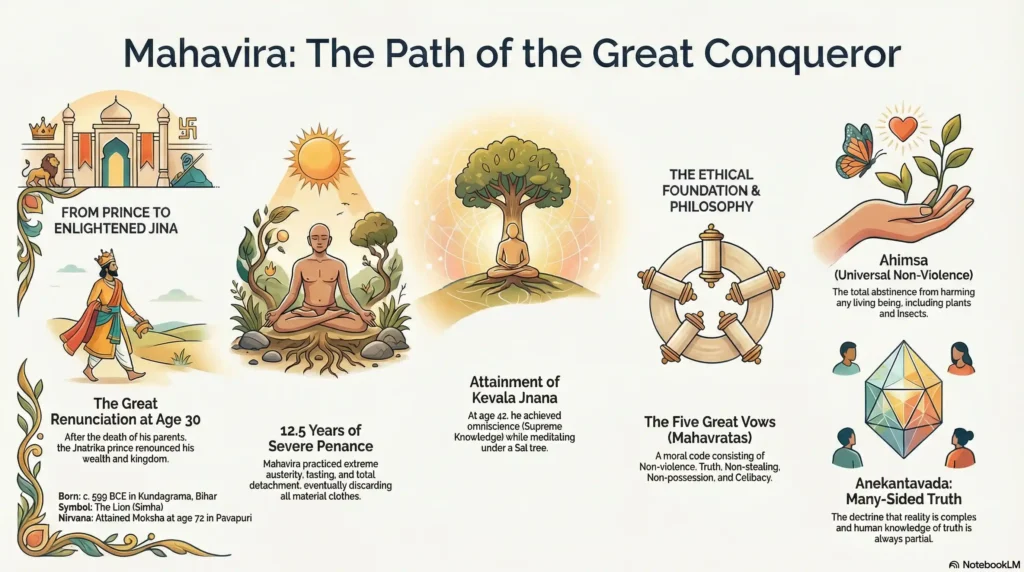

Vardhamana Mahavira (c. 599–527 BCE) was the 24th and last Tirthankara (Ford-maker) of Jainism. Born into the royal family of the Jnatrika clan in Kundagrama (near Vaishali, Bihar), he lived a life of luxury until the age of 30. Driven by a quest for truth, he renounced his kingdom and family to become an ascetic. For 12.5 years, he practiced severe penance, enduring extreme hardships and discarding even his clothes. At the age of 42, he attained Kevala Jnana (Omniscience) under a Sal tree. He spent the next 30 years preaching the doctrine of Ahimsa (Non-violence), Anekantavada (Many-sidedness of truth), and the Three Jewels (Triratna). He attained Moksha (Liberation) at Pavapuri at the age of 72.| Feature | Details |

| Birth Date | c. 599 BCE (Traditional) / 540 BCE (Historical) |

| Birth Place | Kundagrama, Vaishali (Bihar) |

| Original Name | Vardhamana (“The Increasing One”) |

| Father | King Siddhartha (Jnatrika Clan) |

| Mother | Queen Trishala (Licchavi Princess) |

| Clan | Jnatrika (Kshatriya) |

| Wife/Daughter | Yashoda / Priyadarshana (Svetambara belief) |

| Enlightenment | Kevala Jnana (Age 42) under a Sal Tree |

| Death (Nirvana) | Pavapuri, Bihar (Age 72) |

| Symbol | Lion (Simha) |

The Prince of Kundagrama

Vardhamana was born into a powerful Kshatriya family. His father, Siddhartha, was the head of the Jnatrika clan, and his mother, Trishala, was the sister of Chetaka, the powerful king of Vaishali. His birth was preceded by 14 auspicious dreams seen by his mother (16 in Digambara tradition), signaling the arrival of a great soul. He grew up in luxury but remained detached from worldly pleasures.

Rise of Jainism and Buddhism 6th Century BCE: The Shramana Revolution

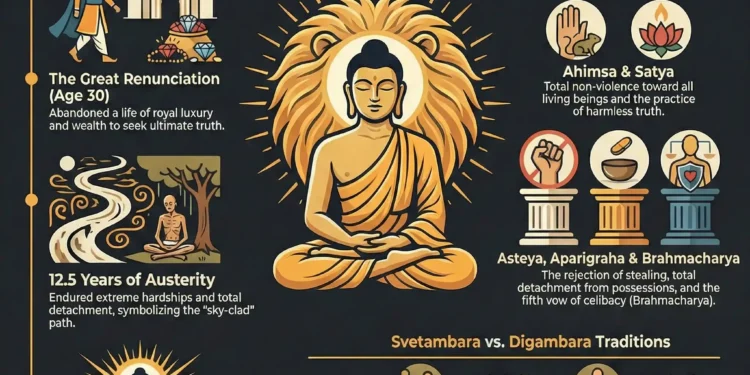

The Great Renunciation

At the age of 30, after the death of his parents, Vardhamana sought his elder brother’s permission to leave the kingdom. He gave away all his wealth and renounced the world.

- The Ascetic Life: Unlike the Buddha, who followed the “Middle Path,” Mahavira chose the path of extreme austerity. He wandered for 12 years, mostly naked, fasting for weeks, and enduring attacks from insects and hostile villagers without retaliation. He famously discarded his clothes after 13 months, symbolizing total detachment from the material world (Digambara – sky-clad).

Enlightenment (Kevala Jnana)

At the age of 42, on the banks of the river Rijuvalika, while meditating under a Sal tree, Mahavira attained Kevala Jnana (Supreme Knowledge or Omniscience).

- The Jina: From this point, he was called Mahavira (Great Hero), Jina (Conqueror of inner enemies like anger and ego), and Nigrantha (Free from bonds). His followers came to be known as Jains.

The Teachings: The Five Vows

Mahavira organized his followers into a four-fold order (Sangha) of monks, nuns, laymen, and laywomen. He added the fifth vow (Brahmacharya) to the teachings of his predecessor, Parshvanatha.

- Ahimsa (Non-Violence): Total abstinence from harming any living being, including insects and plants.

- Satya (Truth): Speaking only the harmless truth.

- Asteya (Non-Stealing): Not taking anything not willingly given.

- Aparigraha (Non-Possession): Detachment from people, places, and material things.

- Brahmacharya (Celibacy): Complete control over the senses (Added by Mahavira).

Life of Buddha c. 563-483 BCE: The Journey to Enlightenment

Philosophy: Anekantavada and Syadvada

Mahavira taught that truth is complex and has multiple aspects (Anekantavada). Just like blind men touching different parts of an elephant describe it differently, human knowledge is partial. This led to the doctrine of Syadvada (“Maybe” or “In some ways”), promoting intellectual tolerance.

The Final Liberation (Moksha)

For 30 years, Mahavira traveled across the Gangetic plains (Bihar, Bengal, UP), preaching in Prakrit (Ardhamagadhi), the language of the masses. At the age of 72, in Pavapuri (near Rajgir), he preached his final sermon and attained Nirvana (liberation from the cycle of birth and death). The lamps lit by the people to compensate for the light of his knowledge that vanished are said to be the origin of the festival of Diwali in Jain tradition.

Later Vedic Period c. 1000-600 BCE: The Age of Iron and Kingdoms

Quick Comparison Table: Svetambara vs. Digambara Views on Mahavira

| Feature | Svetambara (“White-Clad”) | Digambara (“Sky-Clad”) |

| Marriage | Married Yashoda, had a daughter | Remained unmarried (Celibate) |

| Clothing | Wore white robes after enlightenment | Remained completely naked |

| Birth | Embryo transferred from Brahmin to Kshatriya womb | Normal birth |

| Women’s Moksha | Women can attain liberation | Women must be reborn as men to attain Moksha |

| Food | Kevalin (Omniscient) needs food | Kevalin does not need food |

Curious Indian: Fast Facts

- The First Disciple: Mahavira’s first disciple was his son-in-law, Jamali, who later disagreed with him and formed a schism.

- The Contemporaries: Mahavira was a contemporary of Gautama Buddha. Though they lived in the same region and time, there is no historical record of them ever meeting.

- Makkhali Gosala: Before attaining enlightenment, Mahavira spent six years with Makkhali Gosala, who later founded the Ajivika sect. They parted ways due to ideological differences (Gosala believed in fatalism/destiny, Mahavira in Karma/Action).

- Sallekhana: Mahavira endorsed Sallekhana (Santhatra), the practice of voluntarily fasting to death when one’s spiritual mission is complete or the body is no longer useful.

Conclusion

The Life of Mahavira was a radical experiment in human potential. He pushed the boundaries of physical endurance and mental discipline to their absolute limits. His message of Ahimsa—that every living being, no matter how small, has a soul and a right to live—remains the most powerful ethical concept given by India to the world. He taught that the true conquest is not of the world, but of the self.

Reign of Chandragupta Maurya 321-297 BCE: The First Empire of India

If you think you have remembered everything about this topic take this QUIZ

Where was Mahavira born?

He was born in Kundagrama, near Vaishali in modern-day Bihar.

What is “Kevala Jnana”?

It refers to Omniscience or supreme knowledge, which Mahavira attained at the age of 42.

Which vow did Mahavira add to the teachings of Parshvanatha?

He added the vow of Brahmacharya (Celibacy/Chastity).

Where did Mahavira attain Nirvana?

He attained Nirvana at Pavapuri, Bihar.

What is the main symbol of Mahavira?

The symbol associated with Mahavira is the Lion.