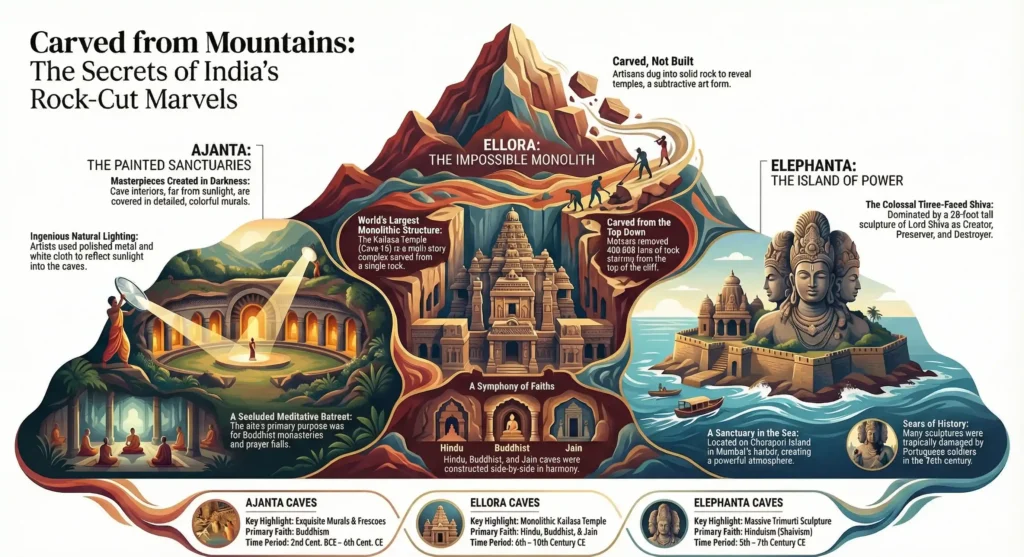

Indian rock-cut architecture represents a unique subtractive art form flourishing between the 2nd century BCE and the 10th century CE, where artisans excavated solid basalt cliffs of the Deccan Plateau rather than assembling stones from the ground up. This engineering marvel is best exemplified by the UNESCO World Heritage sites of Ajanta, Ellora, and Elephanta, which feature mysteries ranging from the light-reflecting murals of deep caves to the "impossible" top-down carving of the monolithic Kailasa Temple. Standing as timeless sanctuaries for Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism, these structures remain a permanent monument to ancient spiritual harmony and technical precision.

| Feature | Details |

| Locations | Aurangabad (Ajanta & Ellora) & Mumbai (Elephanta), Maharashtra |

| UNESCO Status | World Heritage Sites (1983, 1987) |

| Primary Eras | 2nd Century BCE – 10th Century CE |

| Key Faiths | Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism |

| Architectural Marvel | Top-down monolithic excavation (Kailasa Temple) |

The air was thick with the heat of the Indian summer in 1819 when a profound silence was broken not by a tiger’s roar, but by a gasp of disbelief . Captain John Smith, hunting deep in the Sahyadri forest, stumbled upon a horseshoe-shaped gorge that had been hiding in plain sight for centuries .

He hadn’t just found a cave; he had rediscovered a portal to a time when faith moved mountains .

This accidental discovery brought the world face-to-face with the grandeur of Indian rock-cut architecture—a tradition where artisans didn’t build up from the ground, but dug in to the earth .

However, this method is more than just ancient construction; it is a unique subtractive art form . Unlike masonry, where stones are assembled, here, solid natural rock is excavated to reveal the structure hiding within . Imagine a sculptor’s precision applied to an entire cathedral. There is zero margin for error; a single misplaced chisel strike could ruin a pillar or a divine face forever .

Flourishing between the 2nd century BCE and the 10th century CE, this engineering marvel turned the basalt cliffs of the Deccan Plateau into timeless sanctuaries for Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism .

The air was thick with the heat of the Indian summer in 1819 when a profound silence was broken not by a tiger’s roar, but by a gasp of disbelief. Captain John Smith, hunting deep in the Sahyadri forest, stumbled upon a horseshoe-shaped gorge that had been hiding in plain sight for centuries. He hadn’t just found a cave; he had rediscovered a portal to a time when faith moved mountains. This accidental discovery of Ajanta brought the world face-to-face with the grandeur of Indian rock-cut architecture—a tradition where artisans didn’t build up from the ground, but dug in to the earth.

Indian rock-cut architecture is more than just ancient construction; it is a subtractive art form. Unlike masonry, where stones are assembled, here, solid natural rock is excavated to reveal the structure hiding within. Imagine a sculptor’s precision applied to an entire cathedral. There is zero margin for error; a single misplaced chisel strike could ruin a pillar or a divine face forever. This distinct style, flourishing between the 2nd century BCE and the 10th century CE, represents the zenith of ancient engineering, turning the basalt cliffs of the Deccan Plateau into timeless sanctuaries of Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism.

| Feature | Ajanta Caves | Ellora Caves | Elephanta Caves |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Faith | Buddhism (Theravada & Mahayana) | Hindu, Buddhist, Jain | Hindu (Shaivism) |

| Key Highlight | Exquisite Murals & Frescoes | Monolithic Kailasa Temple | Massive Trimurti Sculpture |

| Time Period | 2nd Cent. BCE – 6th Cent. CE | 6th – 10th Century CE | 5th – 7th Century CE |

| Atmosphere | Secluded, Meditative Retreat | Bustling Trade Route Hub | Island Sanctuary |

1. The Impossible Monolith: The Mystery of Kailasa (Ellora)

If you stand at the edge of the precipice looking down into Cave 16 of Ellora, your mind might struggle to comprehend the scale of what lies before you. This is the Kailasa Temple, the crown jewel of Indian rock-cut architecture, and it defies every rule of modern civil engineering.

The most baffling aspect of the Ajanta Ellora caves mystery isn’t about lost treasures, but the sheer logistics of excavation. The architects of the Rashtrakuta dynasty, around the 8th century CE, decided to carve a multi-story temple complex directly out of a basalt cliff. But here is the twist: they didn’t start at the bottom. They started at the top of the mountain and dug down.

Consider the audacity of this plan. Workers removed nearly 400,000 tons of heavy rock over decades. There were no scaffolds to hold up the ceiling because the ceiling was the ground they were standing on. They had to visualize the entire temple—pillars, elephants, staircases, and the central shrine—in three dimensions before a single stone was cut. If an artisan carving a pillar at the bottom made a mistake, there was no way to replace the stone. The entire mountain was the canvas. This “top-down” excavation technique remains one of the greatest unrepeated feats in Indian rock-cut architecture, leaving modern engineers to wonder how they managed debris removal and precise geometric alignment without computer-aided design.

2. Shadows and Light: The Secrets of Ajanta’s Murals

While Ellora shouts with the grandeur of sculpture, Ajanta whispers with the elegance of painting. Stepping into the dark prayer halls (Chaityas) and monasteries (Viharas) of Ajanta, you are greeted by the serene gaze of Bodhisattvas. But as your eyes adjust to the dim light, another question arises regarding these ancient rock-cut temples: How did they paint in the dark?

These caves are deep, cut into the side of a gorge where direct sunlight rarely penetrates the inner sanctums. Yet, the walls are covered in intricate, color-saturated paintings detailing the Jataka tales. The level of detail—the jewelry on a princess, the pattern on a silk robe—is microscopic.

Historians believe the artists used a system of white cloth or polished metal sheets to reflect sunlight from the cave entrance into the deeper recesses. This reflected light would have been soft and diffused, perfect for the tempera technique used here. The artists used local minerals for pigments: red ochre, yellow ochre, lamp black, and the precious lapis lazuli imported all the way from Afghanistan for the vibrant blues. The fact that these colors have survived for nearly 2,000 years in a humid gorge is a testament to the advanced material science inherent in Indian rock-cut architecture.

3. Guardians of the Island: The Enigma of Elephanta

Leaving the mainland and taking a ferry across the Mumbai harbor, you arrive at the Island of Gharapuri, known to the world as Elephanta. The mood here is different. If Ajanta is a retreat and Ellora is a monument, Elephanta is a sanctuary of power, showcasing a different facet of Indian rock-cut architecture.

The caves here are dominated by the sheer scale of sculpture. The focus is the ‘Maheshmurti’ or Trimurti—a colossal 20-foot bust of Lord Shiva. It depicts the deity in three forms: the Creator (Vamadeva), the Preserver (Tatpurusha), and the Destroyer (Aghora). The central face is calm, balancing the fierce energy of the destroyer and the feminine grace of the creator.

However, the Elephanta caves history carries the scars of a violent past. When the Portuguese arrived in the 16th century, they named the island “Elephanta” after a massive stone elephant they found at the landing spot. Tragically, it is said that soldiers used the priceless sculptures inside the caves for target practice. Many of the intricate panels were damaged by musket fire, a heartbreaking loss for Indian rock-cut architecture. Yet, the Trimurti survived, perhaps protected by the sheer awe it inspired. Standing before it today, you feel a connection to the 5th-century devotees who saw this island not just as rocks in the sea, but as the floating abode of the divine.

4. A Symphony of Faiths: Why They Coexist

One of the most touching aspects of these sites is the proximity of the faiths. In a world often divided by religion, Indian rock-cut architecture stands as a permanent monument to harmony. At Ellora, Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain caves were built side-by-side over centuries.

There is no evidence of conflict or destruction between these groups during the construction eras. Instead, they shared techniques. A Hindu artist might have carved a pillar in a Buddhist cave; a Jain monk might have meditated in a hall designed by Hindu patrons. The fluidity of the art styles suggests a society that valued artistic excellence and spiritual pursuit over rigid dogma. The artisans were a guild, a collective of creators whose loyalty was to the stone and the chisel, pushing the boundaries of Indian rock-cut architecture further with every generation.

Asha Bhosle: (September 1933- Present)

Curious Indian: Fast Facts

The “Alien” Theory: Due to the complexity of the Kailasa Temple (Cave 16, Ellora), fringe theories often suggest alien intervention. However, archaeologists confirm it is purely a triumph of human labor and Indian rock-cut architecture.

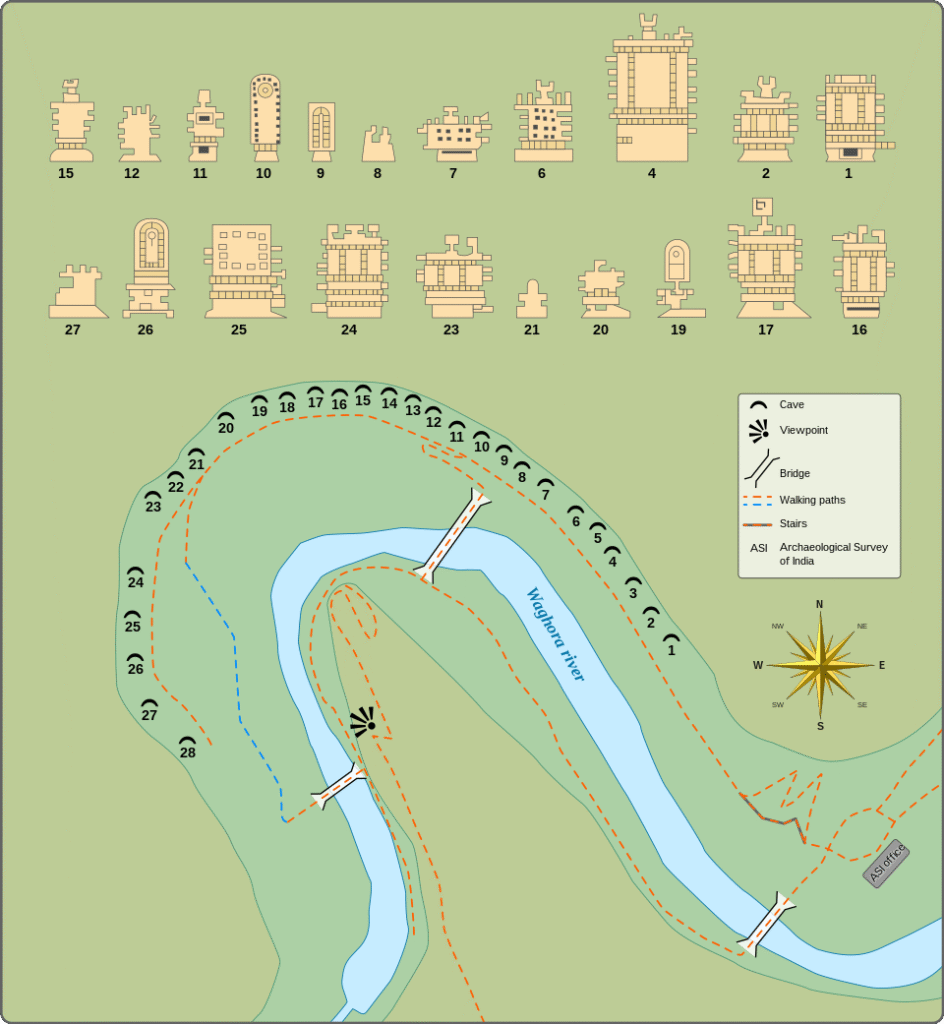

The Unfinished Cave: Ajanta Cave 24 was intended to be the grandest monastery but was left unfinished. It provides a perfect freeze-frame of how the rock was excavated layer by layer.

Sound Engineering: The Gol Gumbaz effect is often cited in later architecture, but the acoustics in the Chaitya halls of Ajanta were designed to amplify the chanting of monks.

Decline: The sites were largely abandoned after the 10th century as structural temples (built from the ground up) became more popular than Indian rock-cut architecture.

If you think you have rememberd everything about this topic take this QUIZ

Results

#1. What is the fundamental difference between the Indian rock-cut architectural style and traditional masonry construction?

#2. What unique and challenging construction method was used to create the Kailasa Temple (Cave 16) at Ellora?

#3. According to the source, how did artisans in the dimly lit Ajanta caves achieve the necessary illumination to paint their detailed murals?

#4. What is the primary artistic and religious highlight of the Elephanta Caves?

#5. The paintings at Ajanta are technically classified as murals in the “tempera” style. What does this mean?

#6. What does the side-by-side construction of Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain caves at Ellora strongly suggest?

#7. What geological feature made the Maharashtra region an ideal location for extensive rock-cut architecture?

#8. The Elephanta Caves suffered significant damage in the 16th century. Who does the source material suggest was responsible for this?

What is the best time to visit Ajanta and Ellora?

The best time to explore these marvels of Indian rock-cut architecture is from November to February when the weather is cooler. The monsoon (June to September) renders the waterfalls at Ajanta spectacular, but travel can be difficult.

How was the Kailasa Temple built?

It was built using the “top-down” excavation method. Artisans started at the top of the rock face and carved downward, removing debris as they went, a unique technique in the history of Indian rock-cut architecture.

Are the paintings at Ajanta frescoes?

Technically, no. They are murals painted in the “tempera” style. The artists applied paint to a dry plaster surface rather than wet plaster (which is true fresco).

Can I visit all three sites in one trip?

Yes, but it requires planning. Ajanta and Ellora are near Aurangabad, while Elephanta is near Mumbai. You can take a train or flight between Mumbai and Aurangabad to see the full spectrum of Indian rock-cut architecture.

Why are there so many rock-cut caves in Maharashtra?

The region is covered by the Deccan Traps, a massive formation of basalt rock. This volcanic rock is hard enough to be durable but soft enough to be carved, making it the perfect medium for Indian rock-cut architecture.