Introduction

Colonial architecture in India charts a fascinating arc from revivalist hybrids to streamlined modernity. The Indo-Saracenic mode fused Indian and Indo-Islamic motifs with Western planning and engineering to project a “local yet imperial” identity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. By the 1930s, Art Deco articulated a new urban modern—geometric, aerodynamic, and tropicalized—spreading across cinema halls and residential precincts, especially in Mumbai. Read together, these two idioms reveal how empire, craft, and cosmopolitan aspiration reshaped India’s civic image between c. 1880 and 1940.

Context and origins

Late-19th-century Britain saw a return to craft values that encouraged looking at regional building traditions; in India, this met the Raj’s desire to naturalize its presence through architecture that appeared culturally embedded.

Indo-Saracenic arose from this moment: Indian and Islamic decorative vocabularies layered onto Western (Neo-Gothic/Neoclassical) plans and construction. By the interwar period, global modernity arrived as Art Deco, adapted to Indian climate, materials, and motifs.

Key features and vocabulary

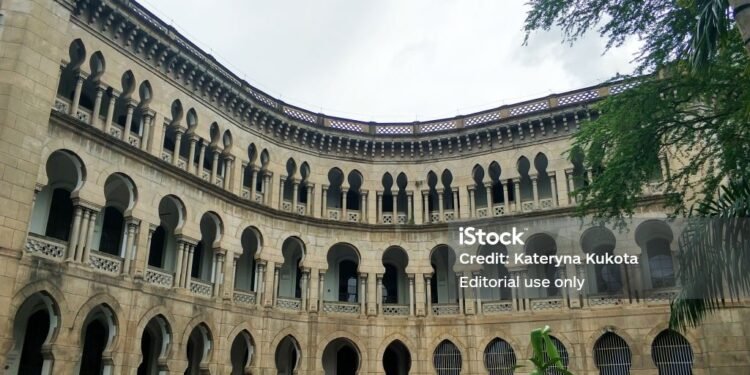

Indo-Saracenic:

Elements: Onion/bulbous domes, cusped/scalloped arches, chhatris, jalis, chhajjas with carved brackets, minarets and kiosks.

Organization: Symmetrical/axial Western planning and steel/brick structure beneath an Indianized envelope.

Materials: Red and buff sandstone, stucco, decorative tile, marble highlights; cast iron and early reinforced systems for spans and galleries.

Art Deco:

Forms: Ziggurats, stepped parapets, curved corners, porthole windows, sunbursts, chevrons, speedlines.

Tropicalization: Deep balconies, verandas, brise-soleil screens, pastel facades; terrazzo floors and metal grills with geometric/Indian motifs.

Programs: Cinemas, apartment blocks, clubs, and seafront ensembles; a city-scale aesthetic of modern convenience and style.

Timeline/evolution

c. 1858–1880s: High Victorian and Neo-Gothic civic projects establish imperial presence; Neo-Classical reasserts for administration and ceremony.

c. 1880s–1920s: Indo-Saracenic becomes a preferred mode for iconic public buildings, palaces, museums, libraries, and railway stations; princely state commissions flourish.

1920s: A swing back to more unequivocal colonial classicism for certain capitals and institutions; parallel interest in regional craft continues in pockets.

1930s–1940s: Art Deco and Streamline Moderne spread through India’s port cities and capitals; hybrid “Indo-Deco” integrates local symbols and climate-smart details.

Iconic examples or schools

Indo-Saracenic highlights:

Mumbai’s civic set including museum and landmark gateways; railway termini that combine Western plan logics with Indian arches, domes, and jalis.

Palace architecture in princely states (e.g., Rajasthan) blending chhatris, jharokhas, and colonnaded courts with modern services and grand axial plans.

Libraries, courts, and colleges across larger presidencies showcasing grafted Indian details atop symmetrical, bi-nuclear Western plans.

Art Deco highlights:

Mumbai’s Oval Maidan ensemble and Marine Drive arc of cinemas and residences—an internationally recognized, coherent urban Deco landscape.

Deco cinema architecture across major cities—marquees, neon, and streamlined foyers—broadcasting modern leisure culture.

Residential precincts with repeating balconies, curved corners, and geometric grills, establishing a local language of urbane apartment living.

Techniques/materials/process

Indo-Saracenic:

Structural systems: Brick masonry, iron/steel trusses, and early reinforced concrete where needed, allowing broad halls and canopies.

Craft overlay: Stone carving for chhatris and brackets; perforated stone/metal screens for ventilation; colored tile and stucco for pattern fields.

Art Deco:

Construction: Reinforced concrete frames enabling curves, cantilevers, and stepped massing; smooth rendered plaster for crisp geometry.

Finishes: Pastel washes; polished terrazzo and mosaic; metalwork with abstracted lotuses, waves, and rays; hardwood detailing adapted to humidity.

How to read/experience

Start with plan vs skin: In Indo-Saracenic, read the Western axial or bi-nuclear plan beneath Indianized surfaces—courts, galleries, and grand entrances reveal the organizing discipline.

Track craft signatures: Spot chhatris at corners, cusped arches at entries, jalis at galleries, and projecting chhajjas—all signaling regional motifs in civic contexts.

For Deco, scan the skyline: Identify stepped profiles, curved balconies, and corner windows; note grills, lobby floors, and door hardware for geometric and “Indo-Deco” iconography.

Climate intelligence: In both idioms, find verandas, deep eaves, and cross-ventilation strategies—heritage aesthetics and thermal comfort working together.

Contemporary relevance/legacy

Urban identity: Indo-Saracenic icons serve as anchors of cultural memory and tourism; Deco ensembles narrate the birth of Indian urban modernity.

Conservation: Seaside weathering, pollution, and insensitive retrofits threaten both vocabularies; preservation demands material-sensitive repairs and regulated signage/services.

Pedagogy and pride: Together, these styles teach hybridity—how local craft, global currents, and state agendas can produce distinctive built languages that still feel Indian.

Conclusion

From Indo-Saracenic’s carefully composed fusions to the confident geometry of Art Deco, colonial-era architecture in India dramatizes a century-long negotiation between empire, craft, climate, and modernity. These buildings are not just facades; they are urban scripts—of public ritual, mobility, cinema, and civic aspiration. To preserve and inhabit them well is to keep alive a layered story of how India became modern on its own terms. If useful, a mapped walking sequence for one city (e.g., Mumbai or Kolkata) can be provided to experience these narratives block by block.