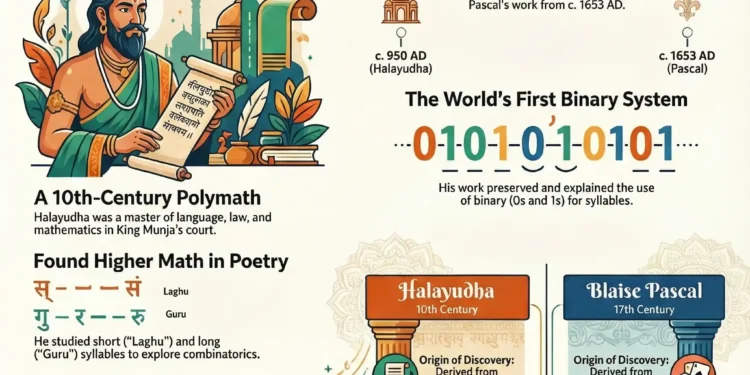

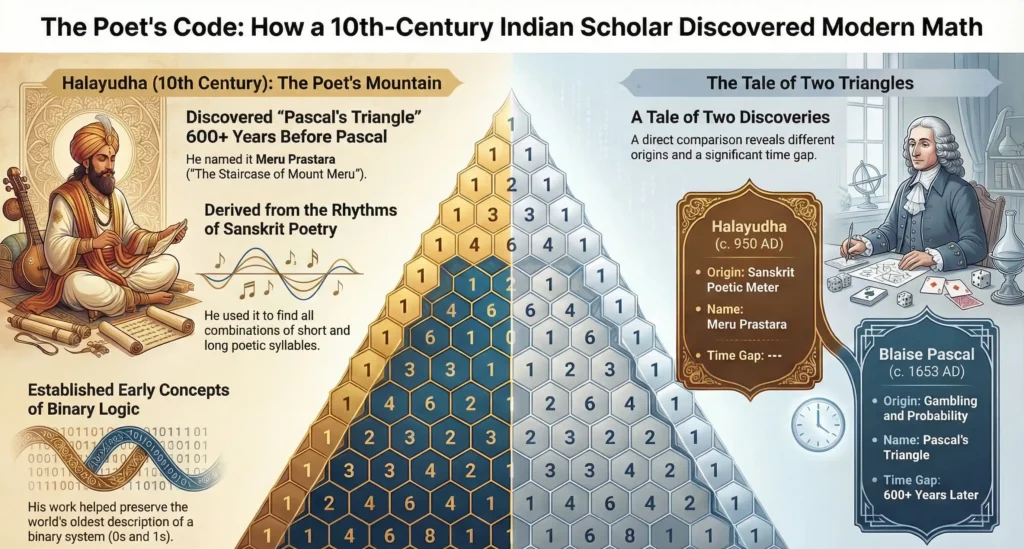

The story of Halayudha is a remarkable journey into a time when the boundaries between literature and mathematics did not exist. Living in the 10th century under the patronage of King Munja, Halayudha wrote the Mritasanjeevani, a deep commentary on ancient Sanskrit prosody. His greatest achievement was the visual and mathematical representation of the Meru Prastara, known today in the West as Pascal's Triangle. By decoding the rhythms of poetry, he provided the foundations for combinatorics and binary logic, proving that Indian thinkers were mapping the infinite long before the European Renaissance.| Feature | Details |

| Name | Halayudha |

| Era | 10th Century CE (c. 950 AD) |

| Major Work | Mritasanjeevani (Commentary on Pingala) |

| Key Discovery | Meru Prastara (Pascal’s Triangle) |

| Patron | King Munja (Paramara Dynasty) |

A Poet in the Court of Kings

The Halayudha life story begins in the vibrant intellectual atmosphere of 10th-century India. This was an era of grand empires and even grander ideas. Halayudha flourished in the court of the Paramara King Munja, a ruler who was himself a poet and a great lover of the arts. In those days, a royal court was not just a seat of power; it was a laboratory of the mind where philosophers, mathematicians, and poets debated the nature of reality under the shade of massive stone pillars.

Halayudha was a polymath—a man whose curiosity could not be contained by a single subject. While he is celebrated today as a mathematician, his contemporaries knew him as a master of language. He understood that language has a heartbeat, a rhythm of long and short syllables that creates the music of a poem. It was this fascination with the “music of speech” that led him to explore the mathematical patterns hidden beneath every verse. He didn’t see numbers as cold symbols; he saw them as the skeleton of beauty.

6 Unfoldings in the Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar Biography

The Mystery of the Number Mountain

At the heart of the Halayudha life story lies a mystery called the Meru Prastara. The name translates to “The Staircase of Mount Meru,” the mythical golden mountain at the center of the universe. Halayudha wasn’t interested in just writing poems; he wanted to know how many different ways a poet could arrange “Laghu” (short) and “Guru” (long) syllables in a verse.

To solve this, he drew a triangular arrangement of numbers. If you look at this triangle, every number is the sum of the two numbers directly above it. In modern classrooms, this is taught as Pascal’s Triangle, named after Blaise Pascal who lived in the 17th century. However, the Indian scientist biography of Halayudha shows that he was using this “mountain of numbers” to solve complex problems in combinatorics more than 600 years before Pascal was even born. It is a profound emotional moment to realize that a 10th-century scholar was doodling the secrets of probability on palm leaves while Europe was in the depths of the Early Middle Ages.

Binary Logic and the Dance of Syllables

The brilliance of the Halayudha life story extends into the world of computer science. Long before the first computer was built, Indian mathematicians like Pingala, and later Halayudha, were working with binary systems. They categorized syllables as either 0 or 1 (short or long). Halayudha’s commentary, the Mritasanjeevani, acted as a bridge, making these ancient, cryptic binary codes understandable for his generation.

Imagine a man sitting by an oil lamp, meticulously calculating every possible variation of a six-syllable line. His work provided a systematic way to map out these variations, effectively creating a “truth table” for combinations. This wasn’t just an academic exercise; it was a spiritual quest to find the perfect harmony in prayer and song. When we look at the Meru Prastara mathematics he left behind, we see the early blueprints for the digital world we live in today. He taught us that the most complex systems can often be found in the simplest rhythms.

The Polymath’s Versatility

Halayudha was not a man who stayed in one lane. Beyond his mathematical genius, his life story includes significant contributions to law and lexicography. He wrote the Abhidhanaratnamala, a brilliant “garland of gems” that served as a dictionary for his time. He was also involved in interpreting the Dharmashastra, showing that his logic was as sharp in social law as it was in geometric triangles.

This versatility is a hallmark of the “Curious Indian” spirit. He believed that to understand one thing deeply, you must understand everything generally. His life was a testament to the idea that science and art are two sides of the same coin. Whether he was defining a word or calculating an infinite series, he approached his work with a sense of wonder. The Mritasanjeevani commentary remains his most enduring legacy, a text that breathed “new life” (which is what Mritasanjeevani means) into the ancient wisdom of his ancestors.

7 Secrets of Padmanabhaswamy Temple Treasure

Comparison: Halayudha vs. Blaise Pascal

| Feature | Halayudha (10th Century) | Blaise Pascal (17th Century) |

| Origin of Discovery | Derived from Sanskrit Poetic Meter. | Derived from Gambling and Probability. |

| Name of Structure | Meru Prastara (Mountain Staircase). | Pascal’s Triangle. |

| Primary Goal | Finding variations in short/long syllables. | Solving the “Problem of Points” in games. |

| Mathematical Basis | Combinatorics and Binary Logic. | Probability Theory and Algebra. |

| Time Gap | Discoveries recorded c. 950 AD. | Discoveries recorded c. 1653 AD. |

A Legacy That Transcends Time

Why does the Halayudha life story matter to us today? It matters because it shifts our perspective on where “modern” ideas come from. For too long, history has been told through a single lens. By uncovering the work of Halayudha, we reclaim a piece of global heritage. He shows us that curiosity is a universal human trait that doesn’t belong to any one century or country.

His work on the Meru Prastara is now recognized by historians of mathematics worldwide as a crucial step in the evolution of algebra. But more than that, he inspires us to look for patterns in our own lives. He reminds us that there is a “mountain of numbers” behind the chaos of the world, and if we are patient and curious enough, we can learn to climb it. His story is not just a record of the past; it is an invitation to the future.

10 Remarkable Facts About Meghnad Saha Life and Achievements

Curious Indian: Fast Facts

- The Name: “Halayudha” literally means “One who has a plow as a weapon,” a name often associated with Balarama, the brother of Krishna.

- The Triangle: The Meru Prastara (Pascal’s Triangle) was used by him to calculate the number of combinations of $n$ syllables.

- The King’s Favor: He was so respected that King Munja granted him a position of high authority in the royal court of Dhara.

- Binary Roots: His work helped preserve the world’s oldest known description of a binary numeral system.

- Dictionary Master: His dictionary, the Abhidhanaratnamala, is still studied by Sanskrit scholars for its precision and depth.

Conclusion

The Halayudha life story is a vibrant thread in the tapestry of Indian excellence. He was a man who saw the infinite in a single line of poetry and the cosmos in a triangle of numbers. By bridging the gap between the beauty of the spoken word and the precision of mathematics, he left behind a legacy that continues to baffle and inspire modern scientists. As we look at the digital screens of the 21st century, we should remember the 10th-century poet who first learned to dance with the binary rhythm of the universe.

If you think you have remembered everything about this topic take this QUIZ

Results

#1. What led Halayudha to explore mathematical patterns like the Meru Prastara?

#2. The Meru Prastara is known in the West by which name?

#3. How did Halayudha contribute to the early foundations of computer science?

#4. What does the title of his famous work, ‘Mritasanjeevani’, literally translate to?

#5. Under whose patronage did Halayudha flourish in the 10th century?

#6. What was the primary goal of the Meru Prastara in Halayudha’s work?

#7. Which of these is another significant contribution of Halayudha outside of mathematics?

#8. What does the name ‘Halayudha’ literally mean?

8 Defining Chapters in the Vikram Sarabhai Biography

Who was Halayudha in Indian history?

Halayudha was a 10th-century mathematician, poet, and scholar who served in the court of King Munja. He is best known for his mathematical commentary on the rules of Sanskrit poetry.

What is the Meru Prastara?

The Meru Prastara is the Indian name for what is now known as Pascal’s Triangle. It is a triangular array of numbers where each number is the sum of the two above it, used to solve problems in combinations.

Did Halayudha invent binary numbers?

While the roots of binary systems go back to Pingala (c. 3rd century BCE), Halayudha’s 10th-century commentary provided the clear mathematical framework that made these binary concepts usable.

What is the significance of the book Mritasanjeevani?

It is a commentary on Pingala’s Chhandasastra. The name means “That which gives life to the dead,” symbolizing how it revived and clarified ancient scientific knowledge.

Why is Halayudha called a polymath?

Because he excelled in multiple unrelated fields, including advanced mathematics, linguistics (lexicography), law, and classical poetry.

Read More: https://curiousindian.in/gautam-buddha-6th-century-bce/