Acharya Kanada was a 6th-century BCE Indian philosopher and the founder of the Vaisheshika school of thought. He is the original architect of atomic theory, proposing that all matter is made of indivisible, eternal particles called Paramanu. His work in the Vaisheshika Sutra also detailed early laws of motion, the concept of momentum, and the chemical transformation of substances through heat, predating similar Western scientific discoveries by over a millennium.| Attribute | Details |

| Name | Acharya Kanada (c. 6th Century BCE) |

| Original Name | Kashyapa |

| Major Work | Vaisheshika Sutra |

| Core Concept | Anu (The Atom) and Paramanu |

| Philosophical School | Vaisheshika (One of the six Darshanas) |

The Sage of Particles: Kanada’s Vision of the Invisible

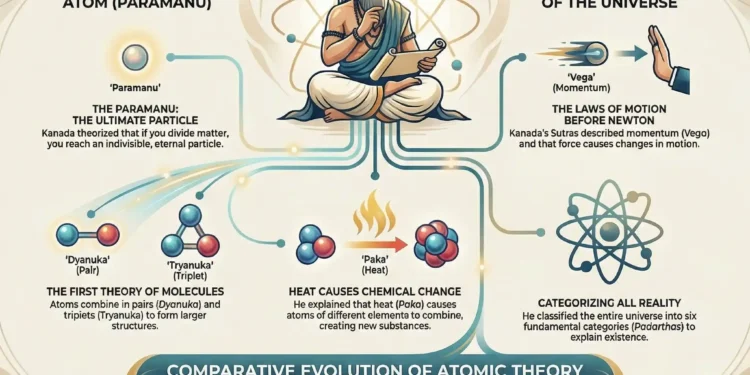

In the quiet, ancient forests near Prabhas Kshetra, a philosopher lived a life so simple that he sustained himself by picking up individual grains of rice left behind by farmers. This peculiar habit earned him the name “Kanada”—the “Atom-Eater” or “Grain-Collector.” But while his hands gathered grains, his mind was gathering the secrets of the cosmos. Through the development of the Kanada Atomic Theory, he became the first person in history to propose that everything we see, touch, and breathe is composed of invisible, indestructible particles. It is a mystery that spans millennia: how did a sage in 600 BCE accurately describe the molecular structure of the world without a single microscope?

Kanada’s masterpiece, the Vaisheshika Sutra, is a rigorous analytical framework for understanding reality. He wasn’t interested in myths; he wanted to categorize the physical world. He proposed that if you keep dividing an object, you eventually reach a point where further division is impossible. This ultimate point of matter is what he called the Paramanu. This was not just a philosophical guess; it was the birth of chemistry and physics in the Indian subcontinent, providing an inspirational blueprint for the scientific method.

10 Remarkable Facts About Meghnad Saha Life and Achievements

The Mystery of the Paramanu

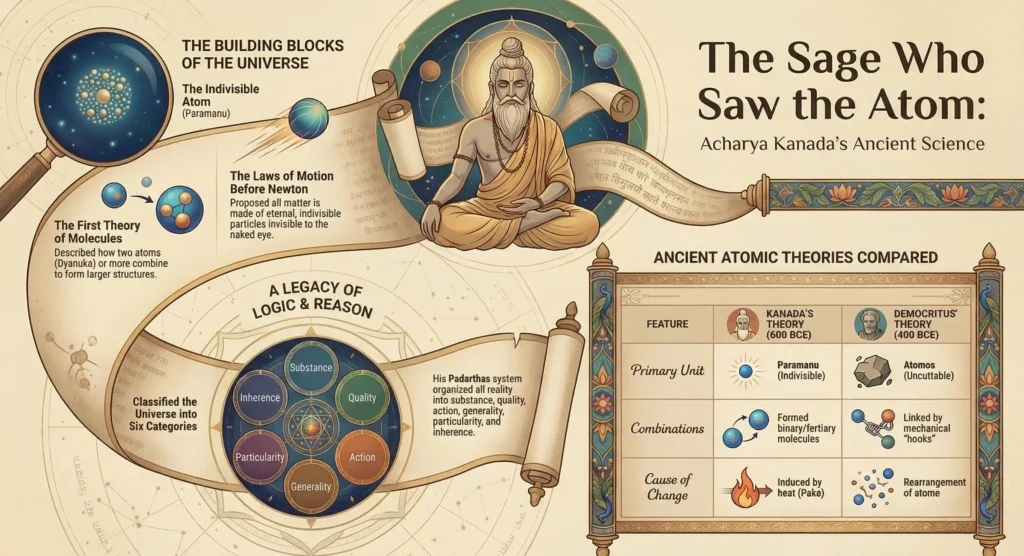

The core of Kanada Atomic Theory lies in the nature of the Anu (atom). Kanada described the atom as eternal, indestructible, and invisible to the naked eye. He argued that atoms do not exist in isolation in the perceptible world but combine in specific ratios to form larger structures. He called a combination of two atoms a Dyanuka (binary molecule) and three pairs of these a Tryanuka (tertiary molecule).

This understanding of chemical bonding was incredibly sophisticated. He explained that atoms of the same element combine to create pure substances, while atoms of different elements combine under the influence of heat (Paka) to create new substances with different properties. This “mystery of transformation” is exactly what modern chemists study today when they look at how heat changes the molecular structure of matter. For any “Curious Indian,” this proves that our ancestors were thinking at a molecular level when the rest of the world was still debating the basic elements.

Dr. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam: (1931-2015)

The Laws of Motion Before Newton

While Kanada is famous for the atom, his work on Karma (motion) is equally staggering. Long before Isaac Newton formalized the laws of motion, Kanada’s Vaisheshika Sutra described the nature of force and movement. He identified five types of motion: upward, downward, contraction, expansion, and horizontal.

More importantly, he discussed the concept of Vega (momentum). He noted that motion is produced by a specific cause and that a change in motion is proportional to the force applied. He even touched upon the concept of gravity, referring to it as the “falling of objects due to the quality of weight.” The emotional weight of this realization is profound—it places the roots of classical mechanics firmly in ancient Indian soil. Kanada viewed the universe as a grand machine governed by logical, predictable laws.

Categorizing the Universe: The Six Padarthas

Kanada’s genius was his obsession with classification. He organized the entire universe into six Padarthas (categories):

- Dravya (Substance): The nine basic substances including earth, water, fire, air, and space.

- Guna (Quality): The properties of matter like color, taste, and smell.

- Karma (Action): The types of physical motion.

- Samanya (Generality): What makes things belong to a group.

- Vishesha (Particularity): What makes an individual thing unique.

- Samavaya (Inherence): The relationship between a part and the whole.

This systematic approach is the hallmark of a scientific mind. He didn’t just want to know what things were; he wanted to know how they related to each other. His life was a testament to the power of observation. By focusing on the smallest possible particle, he was able to explain the largest possible structures of the universe.

A Legacy of Logic and Reason

The influence of Kanada Atomic Theory traveled through the centuries, forming the backbone of the Nyaya-Vaisheshika school of logic. His ideas were debated in the great universities of Nalanda and Vikramshila and eventually influenced the scientific currents that flowed into the Middle East and Europe. While the Greek philosopher Democritus is often cited as the father of atomism, many scholars point out that Kanada’s system was far more detailed, especially regarding the chemical combinations of atoms.

Today, as we look at particle accelerators and the Large Hadron Collider, we are essentially continuing the work that Acharya Kanada started in a small ashram 2,500 years ago. He taught us that the truth is often hidden in the smallest details. For the “Curious Indian,” Kanada is a symbol of our intellectual bravery—a man who looked at a grain of rice and saw the infinity of the atom.

6 Unfoldings in the Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar Biography

Quick Comparison: Ancient Atomic Theories

| Feature | Kanada’s Vaisheshika (600 BCE) | Democritus’ Atomism (400 BCE) | Modern Atomic Theory (1800s+) |

| Primary Unit | Paramanu (Indivisible) | Atomos (Uncuttable) | Atoms & Subatomic Particles |

| Combinations | Binary and Tertiary (Dyanuka) | Mechanical “Hooks” | Covalent/Ionic Bonding |

| Cause of Motion | Internal Force & Adrishta | Random Collisions | Electromagnetism & Gravity |

| Qualities | Color, Taste, Smell inherent | Subjective Perception | Protons, Neutrons, Electrons |

| Change | Heat-induced (Pila-paka) | Rearrangement of shapes | Energy level shifts |

Curious Indian: Fast Facts

- The Rice Sage: He was called Kanada because he survived on grains (Kana) gathered from the fields, signifying his focus on the small.

- The First Laws of Motion: His sutras describe motion as being caused by force and momentum, similar to Newton’s First Law.

- Light and Heat: He correctly identified that light and heat are different forms of the same essential substance (Tejas).

- Indestructibility: He argued that while the forms of objects change, the atoms themselves are eternal and cannot be destroyed.

- Spiritual Physics: For Kanada, understanding the physics of the world was a path to Moksha (liberation) because it removed ignorance.

Conclusion

The genius of the Kanada Atomic Theory is a reminder that India has always been a land of deep scientific inquiry. Acharya Kanada didn’t need laboratories to understand the nature of reality; he used the power of pure reason and acute observation. He showed us that the universe is not a chaotic mystery, but a structured system built from the bottom up. As we explore our history, Kanada stands as a towering figure who bridged the gap between the visible and the invisible. For every “Curious Indian,” his story is an invitation to look closer at the world around us, for even in a single grain of dust, there is a universe waiting to be discovered.

7 Secrets of Padmanabhaswamy Temple Treasure

If you think you have remembered everything about this topic take this QUIZ

Results

#1. What earned the philosopher Kashyapa the name ‘Kanada’ in ancient Indian tradition?

#2. In the Vaisheshika Sutra, what term did Kanada use to describe the ultimate, indivisible point of matter?

#3. How did Kanada describe the formation of new substances through chemical transformation?

#4. Which concept, famously formalized by Isaac Newton, was described by Kanada as the ‘falling of objects due to the quality of weight’?

#5. Among the ‘Six Padarthas’ (categories) of the universe, which one refers to ‘Quality’, such as color or taste?

#6. According to the ‘Quick Comparison’ table, how did Kanada’s theory differ from Democritus’ regarding the cause of motion?

#7. Kanada correctly identified that which two phenomena are different forms of the same essential substance (Tejas)?

#8. For Acharya Kanada, what was the ultimate spiritual goal of understanding the physics of the world?

Is Acharya Kanada the real father of atomic theory?

While Democritus is often credited in the West, Kanada’s Vaisheshika Sutra (600 BCE) provides an earlier and more mathematically detailed description of atomic combinations and chemical changes.

What is a Paramanu?

According to Kanada, a Paramanu is the smallest possible particle of matter that cannot be divided further. It is eternal, invisible, and is the building block of all substances.

Did Kanada talk about gravity?

Yes, he described Gurutva (gravity) as the quality of weight that causes objects to fall to the earth, identifying it as a specific property of earth and water substances.

How did he explain chemical changes?

He proposed the theory of Paka-vada, which suggests that heat causes atoms to rearrange and change their qualities, transforming one substance into another (like clay turning into a pot)

Why is his school called Vaisheshika?

The name comes from the word Vishesha, meaning “particularity.” The school focuses on understanding the unique characteristics that distinguish one substance or atom from another.

Read More: https://curiousindian.in/pa%e1%b9%87ini-mid-1st-millennium-bce/