Introduction

The Emergency was a 21‑month period from 25 June 1975 to 21 March 1977 during which Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, through a presidential proclamation under Article 352 citing “internal disturbance,” imposed a nationwide state of emergency that suspended civil liberties, censored the press, and enabled rule by decree; most opposition leaders were jailed and elections were postponed until its withdrawal in March 1977.

Background: Political crisis and the road to 25 June 1975

- Mass agitations led by Jayaprakash Narayan, economic strains (inflation, unemployment), and governance controversies intensified pressure on the government across 1974–75, especially in Bihar and Gujarat.

- On 12 June 1975, the Allahabad High Court set aside Indira Gandhi’s 1971 election for misuse of state machinery, disqualifying her for six years; the Supreme Court soon granted a conditional stay allowing her to remain PM but not vote in Parliament, escalating political confrontation.

- Late on 25 June 1975, on the PM’s advice, President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed proclaimed an Emergency under Article 352 on grounds of “internal disturbance,” India’s first such peacetime national emergency.

Legal basis and constitutional mechanics

- Proclaimed under Article 352 (as it then stood), citing internal disturbance; the order empowered the executive to curtail fundamental rights, censor media, and postpone elections; Parliament ratified the proclamation in July–August 1975.

- The proclamation remained in force from 25 June 1975 until it was formally revoked on 21 March 1977, whereupon general elections were held.

What changed under the Emergency

- Civil liberties and arrests: Fundamental freedoms were curtailed; over 100,000 political opponents, activists, and journalists were detained, many under MISA (Maintenance of Internal Security Act).

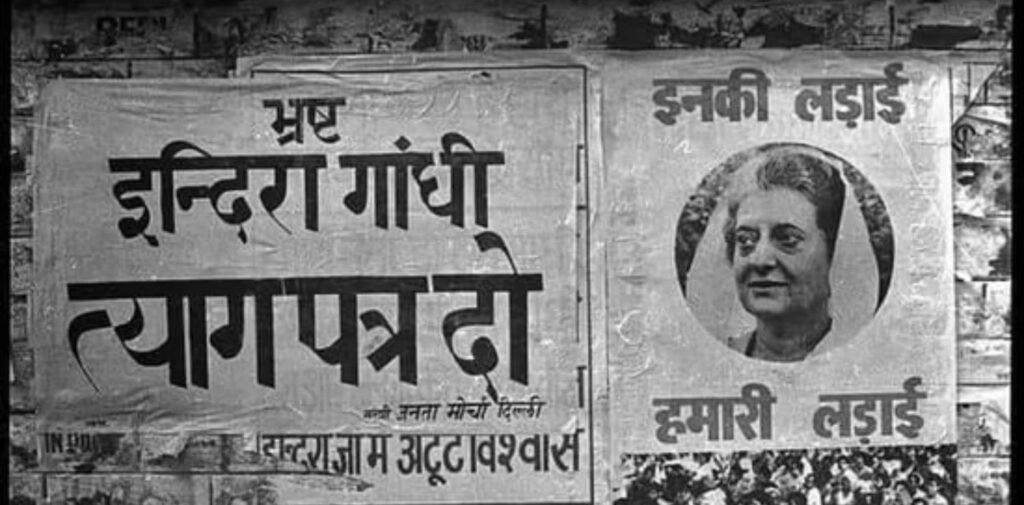

- Press censorship: Pre‑publication censorship and controls on reporting were imposed nationally.

- Governance by ordinance/decree: Executive power expanded sharply; elections to the Lok Sabha were deferred until 1977.

- Coercive programmes: Sanjay Gandhi’s “five‑point” drives included aggressive family planning; large‑scale vasectomy campaigns and slum clearances drew intense criticism for excesses and human‑rights violations.

Key constitutional changes during the period

- Forty‑second Amendment Act, 1976 (“mini‑Constitution”):

- Added “socialist” and “secular” to the Preamble and changed “unity of the nation” to “unity and integrity of the nation.”

- Sought to tilt the balance toward Parliament and the Centre by curbing judicial review, elevating Directive Principles over Fundamental Rights, and expanding the Union’s amending power; also inserted Fundamental Duties.

- Amended Articles 358–359 on suspension of rights during an emergency and widened central authority over states; many provisions took effect between 3 January and 1 April 1977.

- Post‑Emergency recalibration: The 43rd (1977) and especially the 44th Amendment (1978) rolled back several Emergency‑era changes, restored judicial review, protected Articles 20–21 from suspension, and narrowed Emergency grounds to “war, external aggression, or armed rebellion” while requiring a written Cabinet recommendation.

Timeline (selected)

- 12 June 1975: Allahabad High Court verdict against Indira Gandhi’s 1971 election.

- 25 June 1975 (late night): President proclaims Emergency under Article 352; press censorship begins and opposition leaders are detained.

- 26 June 1975: PM’s radio address justifies Emergency citing national stability and disorder.

- July–August 1975: Parliament approves and extends Emergency measures; mass detentions continue.

- 1976: Forty‑second Amendment enacted, overhauling multiple parts of the Constitution and inserting Fundamental Duties.

- 18–20 January 1977: Lok Sabha dissolved and general elections announced for March.

- 21 March 1977: Emergency revoked; moratorium on rights lifted.

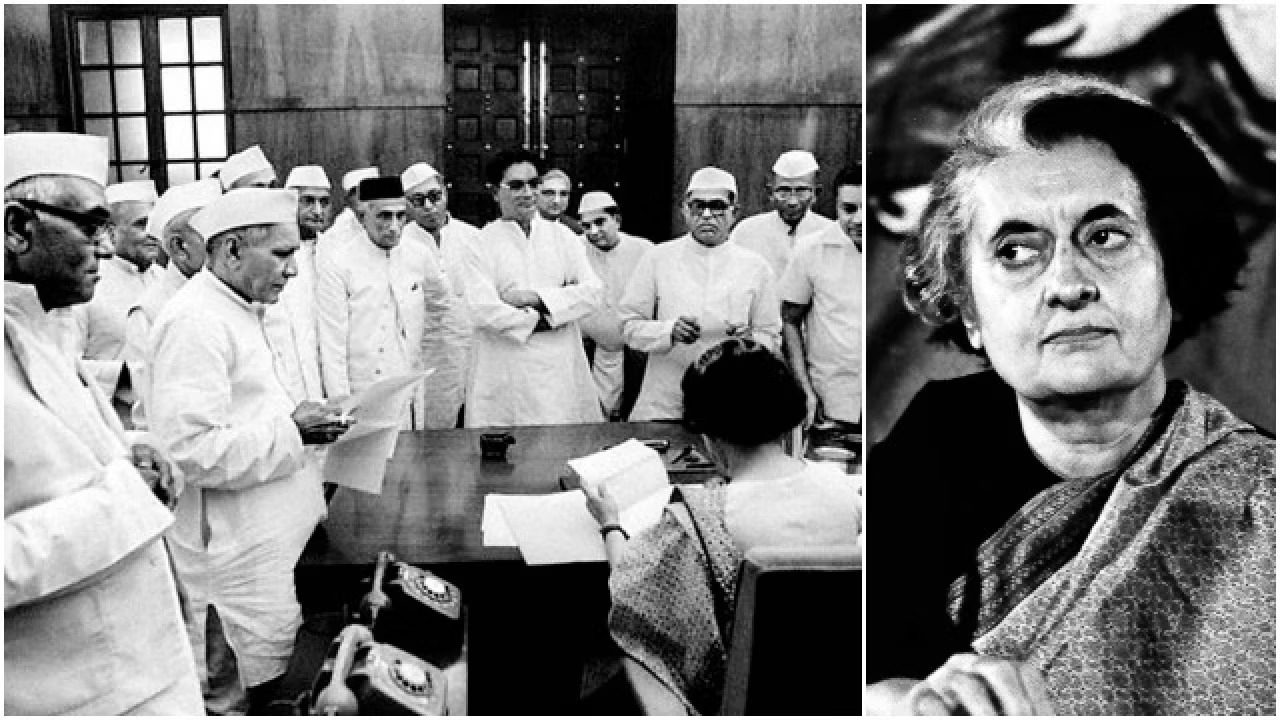

- March 1977: Elections deliver defeat for Indira Gandhi; the Janata Party forms government and launches rollback of Emergency‑era laws.

Why it was imposed (official rationale vs critics)

- Official rationale: The government cited grave internal instability and threats to national security and order, justifying extraordinary powers under Article 352 to restore normalcy.

- Critical assessments: Scholars and opponents argue the Emergency primarily shielded the PM’s position after the election‑law verdict and quelled widespread protest, making it a democratic backslide characterized by mass detentions, censorship, and coercive state action.

Effects on institutions and society

- Judiciary and federalism: The 42nd Amendment attempted to subordinate courts and strengthen central dominance; later rulings (e.g., Minerva Mills, 1980) and amendments restored core checks and balances.

- Politics and parties: The detention of opposition leadership (e.g., JP, Morarji Desai, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, L.K. Advani) fostered anti‑Emergency coalitions that later unseated the Congress in 1977.

- Civil society and media: The period is widely regarded as the darkest chapter for civil liberties in independent India due to censorship, arrests, and coercive campaigns.

Key figures

- Indira Gandhi (Prime Minister): Led the decision to advise Emergency, oversaw its implementation, and authorized extensive political detentions and censorship.

- Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed (President): Issued the proclamation of Emergency on 25 June 1975 under Article 352.

- Sanjay Gandhi: Informal power center promoting controversial programmes, notably the coercive sterilization drive and urban “beautification” demolitions.

- Opposition leaders: Jayaprakash Narayan, Morarji Desai, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, L.K. Advani, and others were arrested early on, becoming symbols of resistance.

Constitutional legacy and safeguards after 1977

- Narrowed grounds and procedural checks: The 44th Amendment removed “internal disturbance” as a ground, substituting “armed rebellion,” mandated written Cabinet advice for Article 352 proclamations, and protected Articles 20 and 21 from suspension even during Emergency.

- Restored judicial review and balance: Subsequent amendments and Supreme Court jurisprudence reaffirmed the basic structure doctrine and re‑empowered courts to check abuse of emergency powers.

Key dates and facts at a glance

- Duration: 25 June 1975–21 March 1977 (21 months).

- Legal basis: Article 352 (then allowed “internal disturbance”); proclamation by President on PM’s advice.

- Major amendment: Forty‑second Amendment Act, 1976 (“mini‑Constitution”), adding “socialist, secular,” inserting Fundamental Duties, and curbing courts; partial rollbacks followed via the 43rd and 44th Amendments.

- End and election: Emergency withdrawn 21 March 1977; polls delivered a historic change of government.

Interesting notes

- Numbers detained: Contemporary tallies cite more than 100,000 political detainees and widespread press censorship during the period.

- Article 352 redefined: Post‑1978, “internal disturbance” was replaced by “armed rebellion,” and emergency suspension of Article 19 was limited to cases of war or external aggression, embedding safeguards against peacetime misuse.

- Media and memory: The period’s 50th anniversary revived national debate on constitutional limits, the 42nd Amendment’s imprint, and the enduring importance of the 44th Amendment’s protections.

Conclusion

The Emergency centralized power, curtailed rights, and reconfigured India’s constitutional order through sweeping amendments and executive control, only to be followed by a decisive electoral repudiation and structural safeguards—via amendments and jurisprudence—that recalibrated emergency provisions to prevent future peacetime abuses while reaffirming judicial review and core fundamental rights.

Leave feedback about this