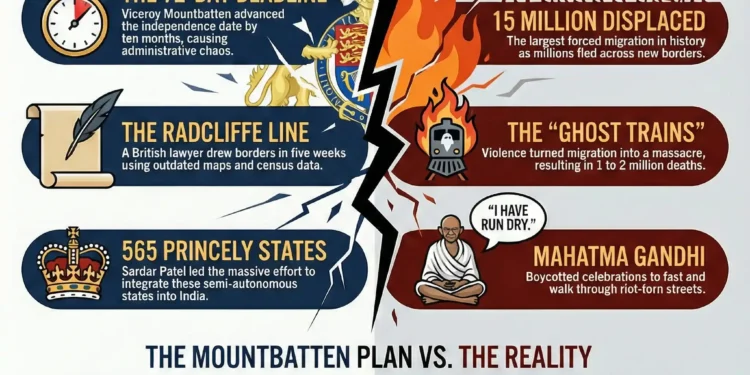

India Independence and Partition 1947 marked the end of nearly 200 years of British colonial rule. On August 15, 1947, the Indian subcontinent was divided into two sovereign dominions: India and Pakistan. This decision, formalized by the Mountbatten Plan and the Indian Independence Act 1947, was accelerated by Viceroy Lord Mountbatten, who moved the date forward by ten months to avoid a civil war. While Jawaharlal Nehru delivered his iconic "Tryst with Destiny" speech in Delhi, millions were fleeing across the new borders in Punjab and Bengal. The partition, executed by the Radcliffe Line, triggered one of the largest and deadliest migrations in history, leaving an estimated 1-2 million dead and 15 million displaced, forever scarring the psyche of the subcontinent.| Feature | Details |

| Independence Date | August 15, 1947 |

| Partition Plan | Mountbatten Plan (June 3 Plan) |

| Boundary Commission | Led by Sir Cyril Radcliffe (Radcliffe Line) |

| Key Leaders | Jawaharlal Nehru, M.A. Jinnah, Lord Mountbatten, Sardar Patel |

| Migration Scale | ~14-15 million people displaced |

| Casualties | Est. 1 million to 2 million dead |

| Princely States | 565 States (Given choice to join India or Pakistan) |

The Rush to Exit

In early 1947, the British Empire was bankrupt and exhausted from World War II. Prime Minister Clement Attlee announced that Britain would leave India by June 1948. However, the new Viceroy, Lord Louis Mountbatten, arrived in March 1947 and decided that waiting that long would lead to anarchy.

Mountbatten made a fateful decision: he advanced the date of independence by ten months, to August 15, 1947. This gave the administration just 72 days to divide a country of 400 million people, a unified army, a railway network, and centuries of shared history. This haste is often cited by historians as the primary cause of the chaos that followed.

The Constitution of India: How 299 Visionaries Scripted a Nation’s Destiny

The Man Who Drew the Line

The task of drawing the border fell to Sir Cyril Radcliffe, a British lawyer who had never set foot in India before. He was given five weeks to partition Punjab and Bengal. Working in a sweltering bungalow in Delhi, armed with outdated maps and census data, Radcliffe drew the line that would separate families, farms, and futures.

Radcliffe kept the line secret until August 17, 1947—two days after independence. This meant that on the day of freedom, millions of people in border villages did not know which country they belonged to. The uncertainty fueled panic, leading to the horrific communal violence that engulfed Punjab and Bengal.

The Tryst with Destiny

On the night of August 14, Delhi was raining. Inside the Constituent Assembly, the mood was electric. As the clock struck twelve, Jawaharlal Nehru rose to deliver the most famous speech in Indian history:

“At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom.”

Outside, the Union Jack was lowered, and the Tricolor was hoisted. For the elite in Delhi, it was a moment of euphoria. But hundreds of miles away, the reality was starkly different.

Assassination of Mahatma Gandhi: The Shot That Silenced a Nation

The Horror on the Trains

While Delhi celebrated, Punjab burned. The Partition triggered a massive exchange of population. Hindus and Sikhs fled from West Pakistan to India, while Muslims fled from India to Pakistan.

The trains became moving coffins. Known as “Ghost Trains,” they would often arrive at stations in Amritsar or Lahore filled only with silent, butchered corpses. In the villages, neighbors who had lived together for generations turned on each other. Women were abducted, and wells were filled with bodies. The violence was not just a side effect of partition; it was a weapon used to cleanse territories.

Gandhi’s Absence

Where was the Father of the Nation on this historic night? Mahatma Gandhi was not in Delhi. He refused to participate in the celebrations. Instead, he was in Calcutta (now Kolkata), walking barefoot through the riot-torn streets of Noakhali. He spent the day fasting and spinning his charkha, trying to stop the communal madness. When asked for a message for the new nation, he simply said, “I have run dry.”

1991 Economic Reforms: How India Pledged Gold to Buy a Future

The Princely Problem

The Indian Independence Act 1947 ended British paramountcy, meaning the 565 Princely States were theoretically free to join India, Pakistan, or remain independent. It took the iron will of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and his secretary V.P. Menon to integrate these states into the Indian Union. Most signed the Instrument of Accession before August 15, but three holdouts—Junagadh, Hyderabad, and Kashmir—would lead to future conflicts.

Quick Comparison Table: The Plan (June 3) vs. The Reality (August 15)

| Feature | The Mountbatten Plan (June 3, 1947) | The Reality (August 1947) |

| Timeline | Orderly transfer of power | Rushed exit; administrative collapse |

| Borders | Defined by Boundary Commission | Announced after independence (Aug 17) |

| Migration | Expected to be peaceful/voluntary | Forced, violent, and chaotic |

| Military | Divided methodically | Caught in crossfire; often partisan |

| Princely States | Theoretical choice given | Diplomatic coercion by Sardar Patel |

Curious Indian: Fast Facts

- Pakistan’s Independence Day: Pakistan celebrates independence on August 14. Mountbatten had to attend the ceremony in Karachi on the 14th before flying to Delhi for the midnight event, so the date was shifted by one day.

- Radcliffe’s Regret: Cyril Radcliffe was so horrified by the violence caused by his boundary line that he refused his fee of £3,000 (₹40,000). He burnt all his papers and left India, never to return.

- Astrology and Independence: Indian astrologers warned that August 15 was an inauspicious date. To bypass this, the ceremony was held at midnight, invoking the traditional Hindu day start (sunrise) vs. the Western day start (midnight).

- The Last Troops: The last British troops, the Somerset Light Infantry, did not leave India until February 1948, marching through the Gateway of India in Mumbai.

Conclusion

India Independence and Partition 1947 was a birth pang like no other. It gave us the world’s largest democracy, but it also left a scar that runs through the heart of the subcontinent. As we celebrate the tricolor today, we must also remember the silence of the ghost trains and the millions who paid the ultimate price for the lines drawn on a map. The story of 1947 is a reminder that freedom is fragile and that the unity of a nation is hard-earned and easily fractured.

The 1969 Bank Nationalization: How Indira Gandhi Seized the Vaults

If you think you have remembered everything about this topic take this QUIZ

Results

#1. Which plan officially formalized the partition of India and Pakistan?

#2. Which British Viceroy advanced the date of independence by ten months to August 1947?

#3. Where was Mahatma Gandhi on the night of August 14, 1947, instead of celebrating in Delhi?

#4. What was the name of the iconic speech delivered by Jawaharlal Nehru on the eve of independence?

#5. Which leader, along with V.P. Menon, was responsible for integrating the 565 Princely States into the Indian Union?

#6. What term was used to describe the trains arriving at stations filled with corpses during the partition violence?

#7. Why did Sir Cyril Radcliffe refuse his fee of £3,000 after drawing the boundary line?

#8. Who was the British lawyer responsible for drawing the boundary line (Radcliffe Line) between India and Pakistan?

Why was August 15 chosen as Independence Day?

Lord Mountbatten chose August 15 because it was the second anniversary of Japan’s surrender in World War II, an event he considered lucky for his career.

Who drew the border between India and Pakistan?

Sir Cyril Radcliffe, a British lawyer, chaired the Boundary Commissions that drew the “Radcliffe Line” dividing Punjab and Bengal.

Why did Mahatma Gandhi not celebrate independence?

Gandhi was distressed by the communal violence and partition. He spent the day in Calcutta, fasting and praying for peace between Hindus and Muslims.

How many people died during the Partition?

Estimates vary widely, but historians generally agree that between 1 million and 2 million people were killed in the communal riots and migration violence.

What was the “Tryst with Destiny”?

It was the historic speech delivered by Jawaharlal Nehru to the Indian Constituent Assembly on the eve of independence, marking the end of British rule.