Introduction

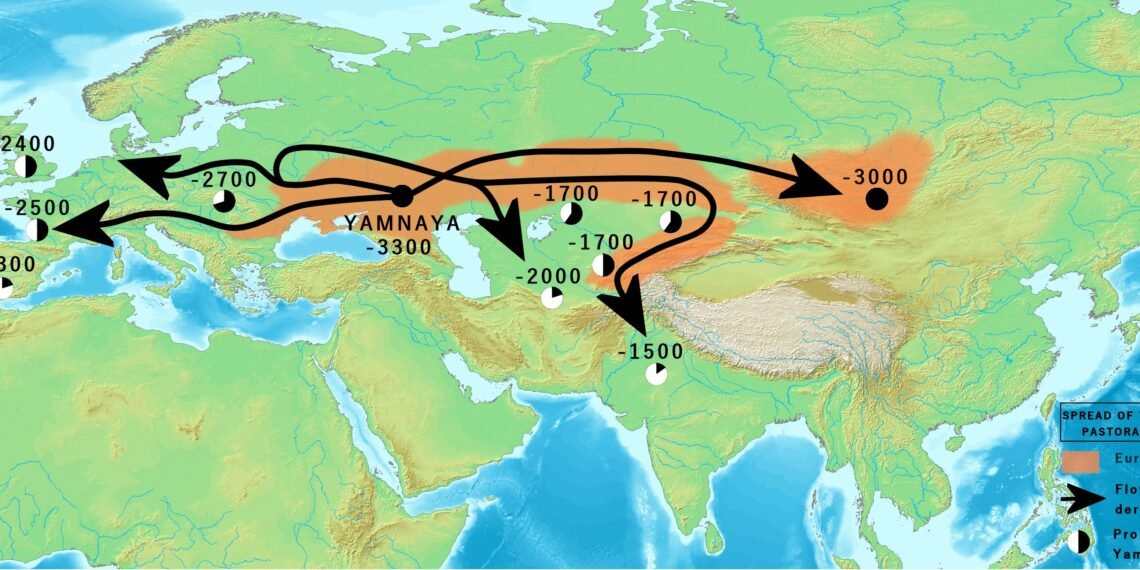

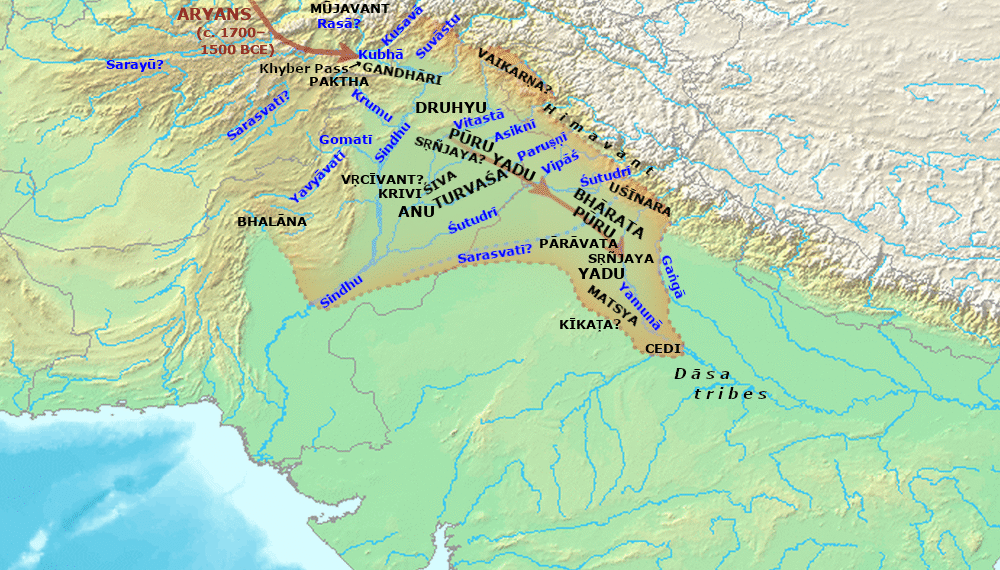

The Vedic Period spans roughly 1500–600 BCE, evolving from the semi‑nomadic, pastoral world of the Rigvedic (Early Vedic) clans in the Sapta‑Sindhu to the agrarian, iron‑age landscape of the Later Vedic age, where territorial janapadas, sharper varna hierarchies, and proto‑urban nodes took shape.

Sources and setting

Knowledge comes primarily from Vedic literature—especially the Rigveda for the Early Vedic phase and the Sama, Yajur, Atharva Samhitas with Brahmanas, Aranyakas, and Upanishads for the Later Vedic—supplemented by material horizons like Painted Grey Ware and early iron in the upper Ganga basin. The Early Vedic heartland was the Sapta‑Sindhu zone along the Indus and its tributaries, later expanding eastward into the Ganga‑Yamuna doab.

Early Vedic polity

Tribe and chiefs: The basic political unit was the jana (tribe), led by the rajan, supported by the purohita and war‑leader (senani); village heads (gramani) coordinated local affairs.

Assemblies: Two key councils—sabha (smaller, elite, with judicial functions) and samiti (wider folk assembly)—checked the chief to varying degrees, with traditions of consultation and occasional selection/election.

Inter‑tribal conflict: The Battle of Ten Kings (Dasharajna) on the Parushni (Ravi) pitted Bharata king Sudas against a confederacy of tribes, ending in a Bharata victory and paving the way for the later Kuru polity.

Early Vedic society and economy

Kinship core: Family (kula) within clan (vis) within tribe (jana) structured social life; women appear in sabha/samiti in references, and some women seers compose hymns.

Varna in formation: The Purusha Sukta reflects a late Rigvedic formulation of four varnas; earlier society retained mobility and occupation was not strictly birth‑fixed.

Herds and fields: Economy was chiefly pastoral with prized cattle (nishka as gold unit appears, but coinage absent), alongside growing agriculture, irrigation by wells/canals, barter, and large gift‑giving (bali, dana).

Early Vedic religion

Rigvedic worship addressed deified natural forces through fire‑rituals: Indra (war, rain), Agni (fire, mediator), Varuna (cosmic order), Soma (ritual elixir), with goddesses like Sarasvati and Ushas also praised; ritual aimed at wealth, cattle, rain, and victory rather than temple‑image worship.

Transition to Later Vedic

By c. 1000–600 BCE, settlement spread east; agriculture intensified; iron (śyama/krishna‑ayas) tools aided forest clearance; and Painted Grey Ware horizons map denser habitation in the upper Ganga valley. Political authority shifted from clan chiefs to territorial kings over janapadas (country‑holding), foreshadowing mahajanapadas.

Later Vedic polity and society

Kingship and bureaucracy: The rajan grew into a more formal monarch with officials (gramani, bhagadhuk tax‑collector, spies), while assemblies waned in political heft, surviving more as aristocratic bodies.

Varna stratification: The varna system hardened into clearer ritual and occupational ranks, with Brahmana–Kshatriya negotiations over precedence reflected in texts; mobility narrowed relative to the earlier phase.

Household and patriarchy: Larger household complexity and patrimony strengthened; sacrificial ideology (Brahmanas) ordered social and ritual life.

Later Vedic economy and material life

Agriculture and iron: Wider plough agriculture with iron implements supported surplus, denser villages, and proto‑urban centers like Hastinapura and Kausambi; woodland clearance advanced settlement fronts.

Pottery and craft: Black‑and‑Red Ware, Black‑Slipped Ware, Painted Grey Ware, and Red Ware indicate diverse ceramic traditions; artisanship and trade grew with caravan routes and nascent market quarters (nagara).

Exchange forms: Gift‑redistribution persisted alongside barter; references to wealth, tribute, and specialized crafts point to increasingly differentiated economies.

Later Vedic religion and thought

Ritual elaboration: The Brahmanas systematized sacrifice, priestly roles, and cosmic correspondences; large soma and animal offerings punctuated royal and social calendars.

Interiorization: Aranyakas and Upanishads turned to philosophical inquiry—Brahman/Atman, karma, renunciation—initiating currents that would shape later Indian thought and sramanic critiques.

Geography and expansion

From the Indus–Sarasvati rivers, the Vedic world moved toward Kurukshetra, the Doab, and farther east (Videha), tracking iron’s spread and PGW settlements; the janapada term in Brahmana texts signals the territorial turn.

Why the Vedic period matters

State formation: It charts the passage from kinship polities to territorial states and the ideologies that legitimized them.

Social orders: It frames the early evolution from fluid social roles toward formal varna stratification that later law books would codify.

Intellectual foundations: It seeds ritual theory and metaphysics—sacrifice, dharma, Atman/Brahman—that structured South Asian religious and philosophical traditions.

Quick facts and anchors

Phases: Early/Rigvedic (c. 1500–1000 BCE), Later Vedic (c. 1000–600 BCE).

Battle of Ten Kings: Sudas defeats a tribal confederacy on the Parushni (Ravi), enabling Bharata–Kuru ascendancy.

Material markers: PGW horizon, early iron spread, proto‑urban Hastinapura/Kausambi in Later Vedic phase.

Conclusion

The Vedic Period traces India’s shift from river‑valley, cattle‑rich clans governed by councils and sacrificial rites to land‑bound kingdoms with iron‑aided agriculture, sharper social ranks, and emergent towns—while simultaneously birthing philosophical currents that would redefine ritual into interior quest. Its layered texts and material horizons together map the long transition from tribe to territory, from hymn to hermeneutics.