Introduction

On May 20, 1498, Vasco da Gama’s fleet made landfall near Calicut (Kappad), completing the first direct European sea voyage to India by rounding the Cape of Good Hope—a breakthrough that reoriented Afro–Eurasian commerce and inaugurated a century of Portuguese naval–commercial expansion in the Indian Ocean world. The voyage proved that monsoon‑timed blue‑water navigation could connect Lisbon to the Malabar spice emporia without transiting Mediterranean–Levantine middlemen, challenging Venetian–Mamluk monopolies and setting the stage for the Estado da Índia.

Background and preparation

By the late 15th century, the Portuguese crown sought to bypass Venetian‑Egyptian spice routes by reaching India via an all‑sea path around Africa, building on reconnaissance by Pêro da Covilhã (overland intelligence) and Bartolomeu Dias (rounding the Cape of Good Hope, 1488). King John II’s strategic vision matured under Manuel I, who selected da Gama—an Order of Santiago noble with court trust—to command a purpose‑built squadron with veteran pilots from prior Atlantic–African runs. The objective fused crusading zeal (“Christians and spices”) with fiscal realpolitik: gain direct access to pepper, ginger, cinnamon, and aromatics, and test whether a royal convoy system could be sustained across the South Atlantic and Indian Ocean.

The 1497–1499 voyage

Fleet and officers: On July 8, 1497, four ships—São Gabriel (flagship), São Rafael, Berrio, and a stores ship—sailed from Lisbon with roughly 170 men, including skilled navigators like Pêro de Alenquer and Pedro Escobar.

Atlantic strategy: After Tenerife and Cape Verde, the squadron executed a deep “volta do mar” into the South Atlantic to pick up westerlies before bearing southeast toward the Cape—an innovation reducing contrary currents and winds.

Cape and East Africa: After passing the Cape, the fleet probed Mozambique (March 1498) and Mombasa (April), encountering hostility in Muslim‑dominated ports, then obtained an experienced pilot at Malindi who rode the monsoon with them across the ocean.

Landfall in India: On May 20, 1498, aided by the pilot’s local knowledge of currents, reefs, and stars, the fleet reached the Malabar coast and anchored near Calicut (Kappad), India’s premier spice entrepôt governed by the Zamorin (Sāmūtiris).

At Calicut: encounter and friction

Calicut’s cosmopolitan bazaar, dominated by seasoned Arab and Persian merchants, received the Portuguese courteously, but da Gama’s royal gifts (cloth, coral, trinkets) seemed paltry in a market accustomed to gold, silver, and fine goods. Muslim traders, wary of a new competitor, counseled the Zamorin against granting privileges to an untested outsider, while da Gama’s formulaic brief—“Christians and spices”—signaled both religious identity and hard commercial intent. Negotiations faltered; no formal treaty was concluded, though da Gama procured a token cargo of spices, proving the route’s viability for the crown’s accountants and fueling plans for annual India Armadas.

The return and cost

Homeward, the fleet fought adverse monsoon winds and disease; the crossing back took far longer, with grievous losses from scurvy and attrition. Berrio limped into Lisbon on July 10, 1499; São Gabriel followed, while da Gama only returned in late August after tending his dying brother at Santiago. Barely 55 of the original 170 men survived, but the strategic math was clear: even a small cargo at European prices could offset appalling human and material costs, encouraging a systematized convoy pipeline.

What the voyage changed

Maritime corridor opened: The Lisbon–Calicut route via the Cape transformed European access to Eastern luxuries—pepper foremost—undermining Venetian–Mamluk margins and redirecting bullion flows toward the Atlantic powers.

Operational template: The India Run standardized into annual armadas—monsoon‑timed, convoy‑escorted, with fortified waypoints—laying institutional foundations for the Portuguese Estado da Índia.

Geopolitical shock: A newcomer armed with ship‑borne artillery and convoy warfare inserted itself into a mature Indian Ocean trading system, triggering a century of competition, coercion, alliances, and naval battles along the Swahili Coast, the Malabar, and beyond.

Limits of the first contact

Da Gama’s initial embassy failed to secure a commercial treaty or a protected factory (feitoria) at Calicut, reflecting misread local protocols, inadequate presents, and underestimation of entrenched mercantile networks. Subsequent armadas (Cabral 1500; da Gama 1502) returned with heavier guns and sharper demands; conflict with Calicut escalated into bombardments and reprisals, marking an early turn from exploratory diplomacy to coercive assertion. The pattern—failed accommodation, then force‑backed bargaining—foreshadowed the militarized commerce that defined early Estado da Índia practice.

Navigation, pilots, and the monsoon

The voyage’s technical heart married Portuguese instrument use (astrolabes, cross‑staffs, latitude sailing) and Atlantic wind logic (volta do mar) with Indian Ocean monsoon rhythm and indigenous pilotage from Malindi. This hybrid seamanship—European blue‑water discipline plus local seasonal knowledge—made the India Run repeatable, demonstrating that global navigation in the 16th century was a cooperative, if unequal, synthesis.

Indian Ocean context

Calicut’s openness derived from its role as a free port linking hinterland pepper producers, Deccan trade routes, and Arab–Persian shipping networks; the Zamorin’s authority rested on keeping that exchange humming. Portuguese demands to privilege a single crown convoy clashed with this pluralistic ecology, while their artillery at sea and desire to police lanes introduced a security logic alien to customary merchant governance. The encounter thus compressed a system built on trust, credit, and cosmopolitanism against a new model of armed, monopolizing convoy capitalism.

High‑yield anchors

Dates and places: Sailed July 8, 1497; rounded the Cape; reached Mozambique (March 1498); Malindi (April); landfall near Calicut (May 20, 1498); return July–August 1499.

Fleet: São Gabriel, São Rafael, Berrio, plus a stores ship; ~170 crew; veteran pilots aboard.

Key enablers: Dias’s 1488 Cape round; Malindi pilot; monsoon‑timed crossing; Atlantic “volta do mar.”

Outcome: Route proven; modest spice cargo; no treaty with the Zamorin; high losses on return; launchpad for annual India Armadas.

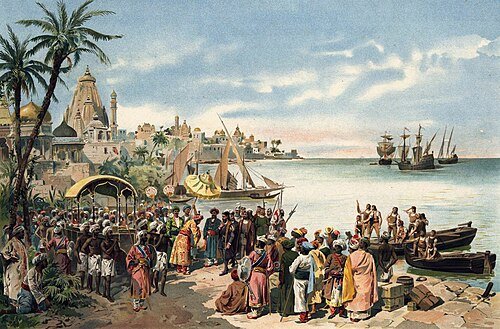

The arrival of Vasco da Gama at Calicut (Kozhikode), by Roque Gameiro, 1900 | Source: Wikipedia

Conclusion

Vasco da Gama’s 1498 landfall at Calicut was a navigational and commercial inflection point, proving a Cape route that knit the Atlantic and Indian Oceans into a single strategic theater. Although initial diplomacy misfired, the voyage unlocked an armada system that redirected European bullion and power into the Indian Ocean, challenging established mercantile orders and foreshadowing centuries of contest over sea lanes and ports from Malindi to Malabar.