Introduction

Timur’s 1398–1399 invasion culminated in the sack of Delhi, where organized massacre, mass enslavement, and systematic plunder devastated the city, shattered already‑brittle Tughluq authority, and accelerated the political fragmentation of North India into successor states like Jaunpur, Malwa, and Gujarat while preparing a later legitimacy bridge for the Timurids (Mughals) via Babur. Advancing from Samarkand through the Indus basin with a hardened composite cavalry, Timur outmaneuvered war elephants near Delhi on 17 December 1398, occupied the capital, and oversaw five days of violence before departing with treasure, artisans, and captives, leaving behind famine, depopulation, and a diminished Delhi Sultanate core.

Who Timur was and why Delhi mattered

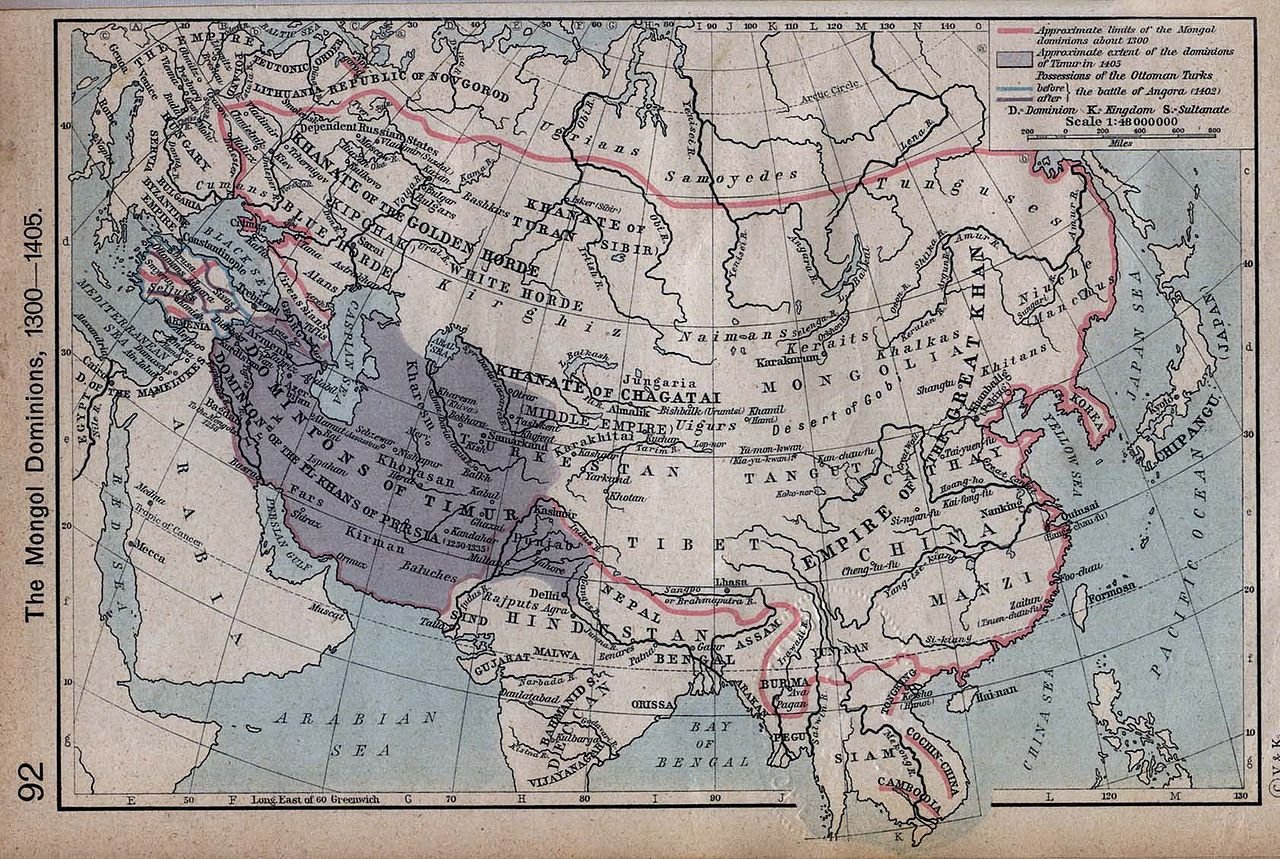

Born in 1336 near Shahr‑i Sabz (Transoxiana), Timur (Tamerlane) built a steppe‑Persianate empire from Khorasan to Mesopotamia, fusing Mongol military organization with punitive terror to force capitulation of cities across Iran, Iraq, and Afghanistan by the 1390s. India represented an extractive frontier: famed for wealth, fractured politically, and within operational reach for shock raids; Timur framed the campaign as a ghazi venture against “kafirs” even as the material aim was plunder and prestige, not occupation.

Delhi on the eve of invasion

The Tughluq state had eroded after Muhammad bin Tughluq’s overextensions and the death of Firuz Shah Tughluq (1388), triggering rapid succession crises between 1388–1394 and empowering regional satraps to ignore Delhi’s writ. Mahmud Tughluq ruled as a figurehead amid factional infighting; provincial governors, Rajput houses, and frontier clans asserted autonomy, creating the “open door” conditions that external predators historically exploit.

The march to the Yamuna

Timur left Samarkand in April 1398, crossed the Indus system by September using boat bridges and fords, and advanced with exemplary brutality—storming Multan, taking Bhattner, destroying temples en route, and driving columns of captives ahead of the army to break resistance in the rear. Near Panipat, he ordered the execution of about one lakh Hindu prisoners to prevent revolt, signaling a terror doctrine calibrated to paralyze local opposition and speed logistics toward Delhi.

Battle outside Delhi (17 December 1398)

Mahmud Tughluq and vizier Mallu Iqbal mustered infantry, cavalry, and 120 elephants to block Timur near Delhi, but steppe tactics prevailed: fire devices, trenches/obstacles, and concentrated missile fire panicked elephants, while mobile cavalry punished exposed flanks. The Delhi line buckled; Mahmud fled toward Gujarat and senior officers dispersed, leaving the capital defenseless within a day of set‑piece contact.

The sack: five days of organized devastation

Timur entered Delhi, then unleashed five days of plunder and slaughter in which inhabitants were herded into Old Delhi precincts and massacred, with chroniclers recalling towers of severed heads as instruments of terror and spectacle. Massive treasure, jewels, and skilled artisans were seized for deportation to Samarkand, while granaries and standing crops were ruined, collapsing food security and turning the city into a famine zone in the weeks after withdrawal.

Administration by design—and departure

Timur declined to garrison Delhi: he confirmed local magnates, appointed Khizr Khan over Punjab and Upper Sind as a Timurid client, and departed within roughly two weeks with caravans of booty and captives, boasting later of monuments in Samarkand built with Delhi labor and spoils. The choice preserved his striking force for western theaters while ensuring Delhi’s continued weakness through a light‑touch patronage that withheld restorative order from the city.

Political consequences in North India

End of the Tughluqs: The invasion was a terminal shock to a failing line; within years, the Tughluqs vanished and the Sayyids rose in a reduced Delhi, governing a shrunken urban‑garrison core.

Successor states: Provincial elites consolidated autonomy: Jaunpur in the Ganga‑eastern Doab, Malwa on the plateau, and Gujarat on the western seaboard, while the Bahmani and Vijayanagara polities dominated the Deccan and south.

Timurid claim and Mughal prelude: Babur’s Timurid descent and Timur’s prior victories in Punjab/Delhi offered a later moral‑political claim to Hindustan, turning a raid’s memory into a legitimacy resource.

Social and economic aftermath

Delhi’s demographic and fiscal bases collapsed: elite and artisan households were killed, enslaved, or deported; accumulated wealth of generations vanished; and artisanal ecosystems were uprooted. With storehouses burned and harvests trampled, famine followed; chroniclers remarked that even carrion birds avoided the air fouled by decomposing corpses for weeks, and recovery stretched across decades as markets and tax circuits struggled to reconstitute.

Ideology, propaganda, and method

Timur’s chronicles and later retellings framed the invasion as religious war while plainly serving the logic of extraction; pre‑battle massacres, exemplary punishments, and city sacks mirrored his Iranian and Iraqi campaigns. This terror‑spectacle was instrumental: it reduced siege times, discouraged garrison resistance, and minimized attritional costs, allowing a smaller core of elite cavalry to traverse large theaters quickly with disproportionate effect.

Why the invasion mattered

Strategic reset: By destroying Delhi’s capacity to arbitrate North India, Timur precipitated a long phase of regionalization in which Delhi became one power among many rather than the system’s center.

Memory and caution: The sack became shorthand for urban apocalypse in north Indian memory, shaping later policy fears about overcentralized capitals without resilient provincial lattices.

Lineage leverage: A century later, the Timurid link converted remembered violence into dynastic legitimacy, enabling Babur to yoke Central Asian pedigree to an Indian throne.

High‑yield anchors

Dates and route: April–December 1398 approach; Indus crossings in September; Delhi battle 17 December; five‑day sack; withdrawal by early 1399.

Opponents and tactics: Mahmud Tughluq/Mallu Iqbal routed; elephants neutralized by fire, obstacles, archery; mobile cavalry exploitation decisive.

Atrocities and plunder: Prisoner massacre near Panipat; temple destructions en route; towers of heads; artisans/treasure deported to Samarkand.

Aftermath: Tughluqs collapse; Sayyids rise; successor states proliferate; famine and long demographic‑fiscal recovery in Delhi.

Bayezid I at the hands of Timur. After defeating Bayezid at Ankara, Timur became the preeminent ruler in the Muslim world and Eurasia | Source: Wikipedia

Conclusion

Timur’s Delhi campaign was a raid scaled to empire: a monsoon‑seasoned cavalry force crossed difficult rivers and hills, weaponized terror, neutralized elephants, and ripped the wealth and people out of a storied capital without the burden of occupation. In doing so, it converted Delhi’s internal fragility into systemic regionalization, seared a memory of devastation into political culture, and left a lineage claim that, a century later, would be refashioned into the Mughal project—proof that even a brief incursion can reset a subcontinent’s political grammar.