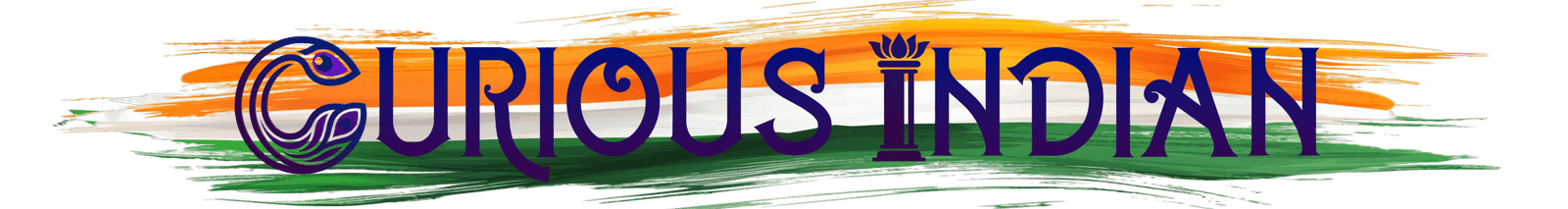

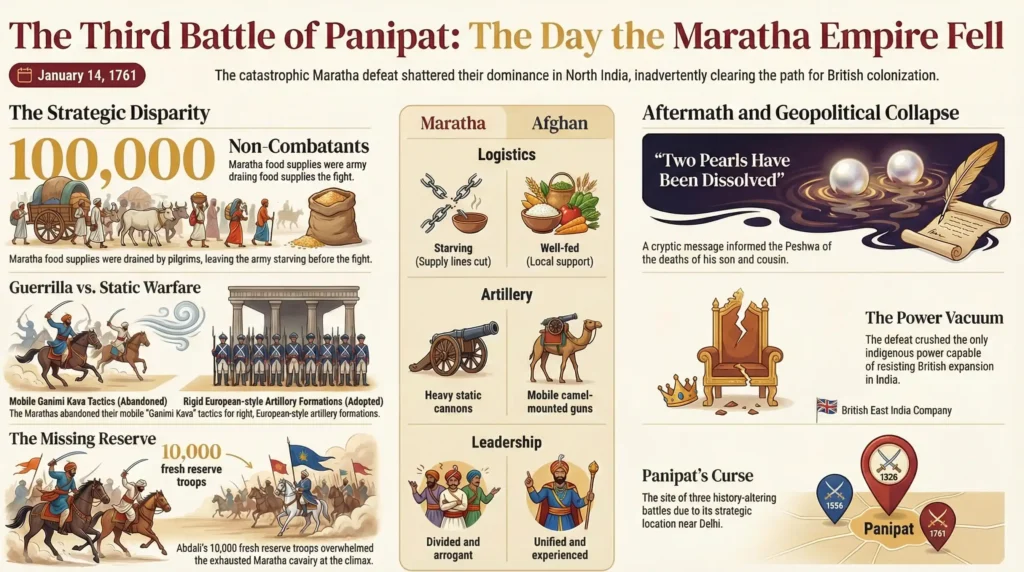

The Third Battle of Panipat, fought on January 14, 1761, was a catastrophic conflict between the Maratha Empire and the invading Afghan army of Ahmad Shah Abdali (Durrani). The Marathas, led by Sadashivrao Bhau, were attempting to defend Delhi and extend their influence into the Punjab. They were opposed by Abdali, who was supported by Indian allies like the Rohillas and Shuja-ud-Daula (Nawab of Awadh). The battle resulted in a decisive Afghan victory. Over 40,000 Maratha soldiers were killed on the battlefield, and countless non-combatants were massacred in the aftermath. The defeat shattered the Maratha confederacy for a decade and created a power vacuum in North India that the British East India Company eventually filled.| Feature | Details |

| Date | January 14, 1761 (Makar Sankranti) |

| Location | Panipat (Present-day Haryana) |

| Maratha Commander | Sadashivrao Bhau (Actual) / Vishwasrao (Nominal) |

| Afghan Commander | Ahmad Shah Abdali (Durrani) |

| Key Allies (Afghan) | Najib-ud-Daula (Rohillas), Shuja-ud-Daula (Awadh) |

| Maratha Strength | ~45,000 Combatants + 100,000 Pilgrims |

| Afghan Strength | ~60,000 Combatants + Reserve Allies |

| Outcome | Decisive Afghan Victory / Maratha Massacre |

The Rise of the Marathas

By the mid-18th century, the Mughal Empire existed only in name. The real power in India was the Maratha Confederacy. From their base in Pune, the Peshwas had planted their saffron flag (Bhagwa Jhanda) as far north as Attock (in modern-day Pakistan).

However, their rapid expansion alarmed the Muslim potentates of North India. Najib-ud-Daula, the Rohilla chief, invited the Afghan ruler Ahmad Shah Abdali to invade India and “save Islam” from the “infidels.” Abdali, seeing an opportunity for plunder and territory, crossed the Indus.

Battle of Buxar 1764: The Victory That Made British Rule Inevitable

The Strategic Blunder

The Peshwa, Balaji Baji Rao, dispatched a massive army north under the command of his cousin, Sadashivrao Bhau. The nominal leader was the Peshwa’s son, Vishwasrao.

Bhau was a brilliant administrator but an arrogant general. He alienated potential allies like the Jats (under Suraj Mal) and the Rajputs. Consequently, the Marathas fought alone. Worse, Bhau brought along nearly 100,000 non-combatants—pilgrims, wives, and children—who drained the army’s food supplies. By the time they reached Panipat, the Maratha camp was starving.

The Battle Formation

On the morning of January 14, 1761, desperate and out of food, the Marathas decided to break the Afghan blockade.

- The Maratha Plan: Use their famed French-trained artillery under Ibrahim Khan Gardi to blast a hole in the Afghan lines.

- The Afghan Plan: Abdali, a military genius, held back a reserve force and used his Zamburaks (camel-mounted swivel guns) to harass the Maratha cavalry.

Death of Tipu Sultan: The Fall of the Tiger of Mysore

The Day of Slaughter

The battle began well for the Marathas. Ibrahim Gardi’s cannons decimated the Rohillas on the right flank. The Maratha cavalry charged, and for a moment, it seemed the Afghans would break.

But at 1:00 PM, tragedy struck. A stray bullet hit Vishwasrao, killing him instantly. Seeing their leader fall, Sadashivrao Bhau descended from his elephant and plunged into the fight, disappearing into the chaos. The sight of the empty howdah panic the Maratha troops.

At this critical moment, Abdali played his ace card. He unleashed his 10,000-strong reserve corps (Qizilbash). Fresh and well-fed, they slaughtered the exhausted and starving Marathas. By sunset, the battlefield was a graveyard.

The Peshwa’s Heartbreak

Back in Pune, the Peshwa was anxiously waiting for news. He received a cryptic merchant’s message:

“Two pearls have been dissolved, twenty-seven gold coins have been lost, and of the silver and copper, the total cannot be cast.”

The “two pearls” were his son and cousin. The “gold coins” were his generals. The shock was too great; Balaji Baji Rao died of a broken heart weeks later.

Annexation of Punjab 1849: The Fall of the Sikh Empire

Why Did the Marathas Lose?

- Starvation: The Maratha army had not eaten properly for days before the battle.

- Loss of Allies: The Marathas had no support in North India, while Abdali united the Muslim chiefs (Awadh and Rohillas).

- Artillery vs. Mobility: The Marathas abandoned their traditional guerrilla warfare (Ganimi Kava) for a static, European-style battle which didn’t suit their cavalry.

- Abdali’s Generalship: Abdali’s use of reserves and camel guns was superior to Bhau’s rigid tactics.

Quick Comparison Table: Maratha Army vs. Afghan Army

| Feature | Maratha Army | Afghan (Durrani) Army |

| Strategy | Heavy Artillery & Shock Cavalry | Mobile Artillery & Reserve Tactics |

| Logistics | Starving (Supply lines cut) | Well-fed (Local support) |

| Key Unit | Gardi Musketeers | Qizilbash Heavy Cavalry |

| Artillery | Heavy static cannons | Zamburaks (Camel-mounted) |

| Leadership | Divided / Arrogant | Unified / Experienced |

| Objective | Defend India/Delhi | Plunder & Religious War |

Curious Indian: Fast Facts

- Ibrahim Khan Gardi: The commander of the Maratha artillery was a Muslim who remained loyal to the Hindu Marathas till his last breath. He was captured and tortured to death by the Afghans for his loyalty.

- The Survivor: Mahadji Shinde, who would later resurrect Maratha power, fought at Panipat. He was wounded in the leg, leaving him with a permanent limp, but he survived to become the kingmaker of Delhi.

- The Loot: Abdali took so much plunder that his army reportedly struggled to carry it back to Afghanistan. However, his soldiers mutinied over unpaid wages, forcing him to leave India sooner than expected.

- Panipat’s Curse: Panipat has been the site of three major battles (1526, 1556, 1761) that changed India’s history, likely due to its strategic location on the Grand Trunk Road guarding Delhi.

Conclusion

The Third Battle of Panipat was a hollow victory for Abdali, who gained little territory, but a devastating blow to India. It crushed the only indigenous power capable of ruling the subcontinent. As historians often say, “Panipat did not decide who would rule India, but it decided who would NOT.” With the Marathas broken, the path was cleared for a new power rising in Bengal—the British.

Establishment of the British Raj 1858: The Dawn of Imperial India

If you think you have remembered everything about this topic take this QUIZ

Who fought the Third Battle of Panipat?

It was fought between the Maratha Empire (led by Sadashivrao Bhau) and the Afghan Army (led by Ahmad Shah Abdali).

When was the battle fought?

It was fought on January 14, 1761.

Who won the Third Battle of Panipat?

Ahmad Shah Abdali won the battle, inflicting a crushing defeat on the Marathas.

Who was Ibrahim Khan Gardi?

He was a Muslim general who commanded the Maratha artillery. He refused to desert the Marathas and was executed by the Afghans after the battle.

What was the main consequence of the battle?

It halted Maratha expansion in the North for a decade and weakened Indian resistance, allowing the British East India Company to consolidate power in Bengal and eventually the rest of India.