Introduction

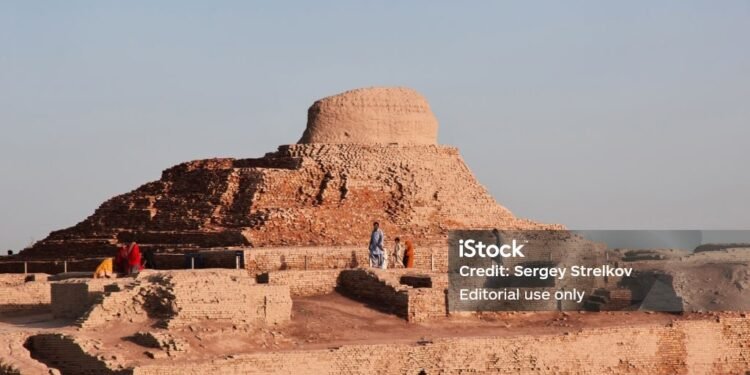

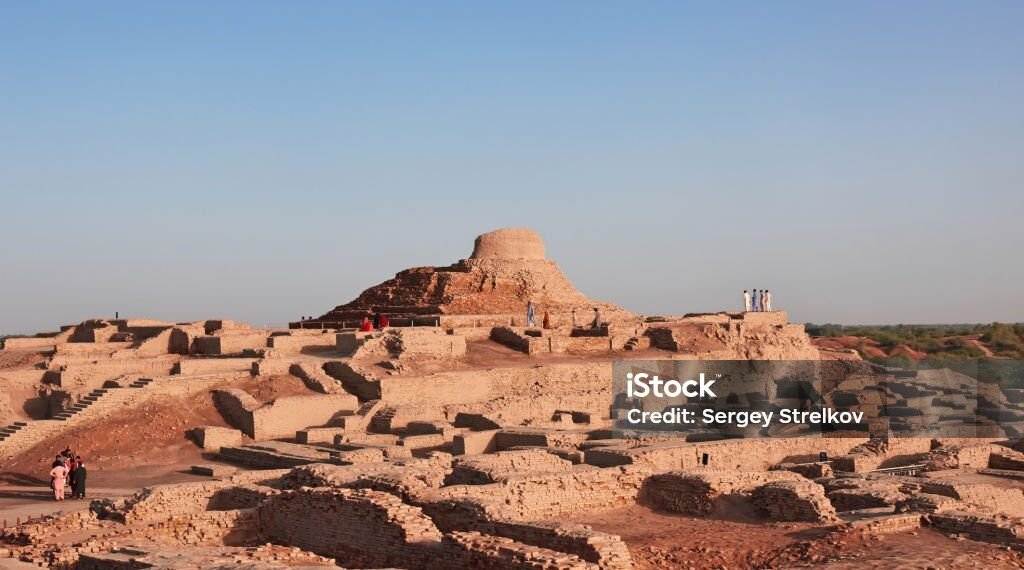

The Indus Valley Civilization (Harappan Civilization) was a Bronze Age urban society flourishing c. 2600–1900 BCE, renowned for planned cities, standardized bricks, elaborate drainage, craft specialization, and long‑distance trade, with major urban hubs at Mohenjo‑daro, Harappa, Dholavira, Rakhigarhi, and Ganeriwala.

Chronology and geography

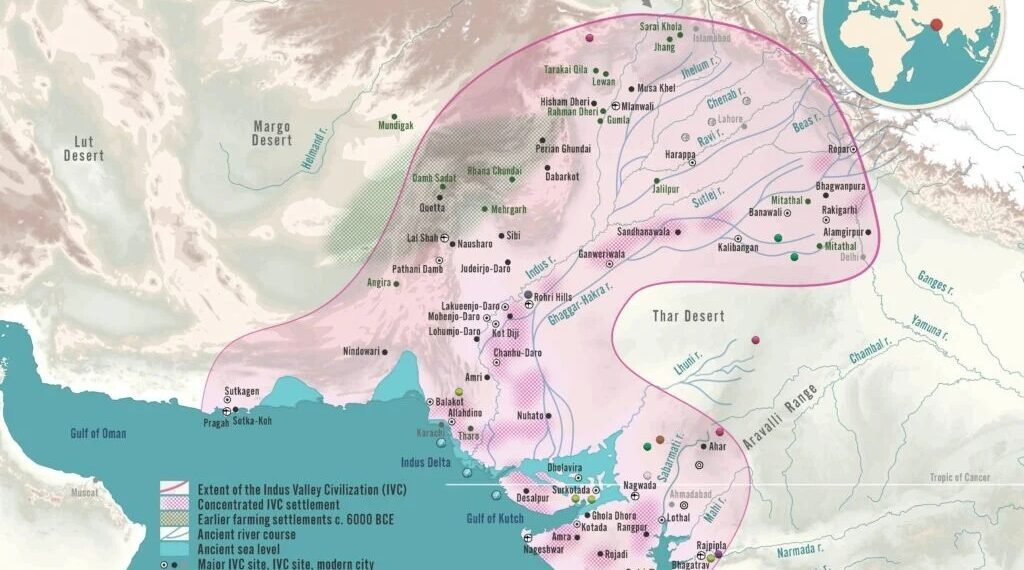

Scholars periodize the culture into Early (c. 6000–2600 BCE), Mature (c. 2600–1900 BCE), and Late Harappan (c. 1900–1300 BCE) phases, marking a trajectory from regional village complexes to large, standardized cities and then to regionalized post‑urban cultures. Its distribution spans present‑day Pakistan and northwest–western India across the Indus, Ghaggar‑Hakra, and their tributaries, with coastal nodes linking Gujarat to Gulf routes.

Urban planning and water systems

Grid and zoning: Cities used orthogonal street plans with citadel precincts and lower towns, indicating hierarchical functions and civic foresight.

Drains and baths: Covered street drains, soak pits, house baths, and private wells linked domestic hygiene to citywide sanitation; Mohenjo‑daro’s Great Bath epitomizes hydraulic engineering.

Water harvesting: Dholavira developed a massive reservoir network, damming seasonal streams (Manhar, Mansar) and integrating cisterns within fortifications for drought resilience.

Sites to know

Mohenjo‑daro: UNESCO site with the Great Bath, large granary precincts, extensive drains, and iconic art (Dancing Girl, bearded “priest‑like” figure).

Harappa: Brick platforms, possible granaries, worker quarters, copper/bronze craft, and standardized metrology cores.

Dholavira: Three‑part urban plan (citadel–middle town–lower town), monumental waterworks, and signboard‑like inscription.

Lothal: Evidence of a trapezoidal dockyard with sluices and spillways, bead workshops, and mercantile quarters linked to Gulf trade.

Metrology, standardization, and administration

Harappans used uniform weights in binary and decimal sequences alongside standardized brick ratios (notably 1:2:4), suggesting coordination across far‑flung settlements. Ivory scales and chert cube sets attest precise measurement, while replicated seal motifs and scripts indicate shared administrative and commercial practices.

Script and seals

Indus script: Short inscriptions on seals, tablets, pottery, and metal remain undeciphered, leaving language affiliation debated (often hypothesized as Dravidian/Elamo‑Dravidian by some).

Seals: Steatite seals depict animals (unicorn, humped bull), composite beings, and ritual scenes, likely used for identification, sealing goods, and denoting authority in trade.

Economy and trade

Agrarian base: Floodplain wheat, barley, pulses, and cotton underwrote urban surplus; spindle whorls and textile imprints confirm cotton weaving and possibly woollens.

Crafts: Bead‑making (agate, carnelian, lapis), faience, shell/ivory carving, copper‑bronze metallurgy, and specialized workshops (Lothal, Chanhudaro) reveal high craft organization.

Exchange networks: Mesopotamian records mention Meluhha (widely identified with the Indus region), reflecting commerce via Dilmun and Magan for copper, shell, timber, lapis, and finished beads.

Art and material culture

Bronze: The 10.5 cm Dancing Girl statuette from Mohenjo‑daro, made by lost‑wax casting, shows kinetic poise, coiled hair, and stacked bangles—an emblem of Harappan figuration.

Stone and terracotta: The bearded male (steatite) and red sandstone torso exemplify stylistic range; terracotta mother‑goddess figurines, toys, and masks indicate popular religiosity and domestic play.

Pottery: Red ware with black geometric/faunal designs, including perforated pottery, shows technological control and possible specialized uses.

Society, polity, and religion

Social texture: Variation in house sizes, burial goods, and artifact quality suggests stratification, though the archaeological record lacks clear palaces or royal iconography.

Governance: Empire‑wide monarchies are unproven; instead, uniform standards and large public works imply strong urban authorities or federated city governance coordinating labor and resources.

Beliefs: The Great Bath hints at ritual ablutions; terracotta female figures point to fertility cults; the “Pashupati”‑type seal in yogic posture suggests elite ritual symbolism, though meanings remain debated.

Science, technology, and everyday life

Engineering: Precision drains, corbelled wells, and baked‑brick architecture show materials science and civic design acumen.

Measurement: Binary/decimal weights, calibrated scales, and uniform brick sizes reflect a culture of quantification in trade and construction.

Textiles and adornment: Cotton threads on tools, bead factories, and diverse ornaments (gold, stone, bone, faience) indicate fashion economies and skilled artisanal labor.

Late Harappan transition and legacy

After c. 1900 BCE, urban uniformity yielded to regional cultures (Cemetery H, Jhukar, Bara, Rangpur), with smaller settlements, reduced long‑distance exchange, and fewer inscriptions, as populations dispersed eastward toward the Ganga‑Yamuna Doab. The Harappan template—grids, drains, standardized measures, and coastal mercantile orientation—left durable habits of planning and exchange in the subcontinent’s later historical urbanisms.

How we know: archaeology and interpretation

Modern understanding arises from excavations at Harappa and Mohenjo‑daro in the 1920s and scores of later digs, alongside artifact studies in metrology, craft residues, and palaeoenvironmental analysis; interpretations evolve as new finds (e.g., Dholavira waterworks) recalibrate older models. The undeciphered script keeps governance and religion partly opaque, but the material record still reveals a society that built cleanliness, measurement, and coordination into its civic DNA.

Key facts for quick recall

Phases: Early, Mature, Late Harappan (c. 6000–1300 BCE range for cultural sequence; urban zenith c. 2600–1900 BCE).

Major sites: Mohenjo‑daro, Harappa, Dholavira, Rakhigarhi, Ganeriwala; Lothal as a port‑workshop node.

Hallmarks: Gridded streets, covered drains, standardized bricks and weights, undeciphered script, long‑distance trade, high craft specialization.

Mohenjo daro ruins close Indus river in Larkana district, Sindh, Pakistan

Conclusion

The Indus Civilization fused pragmatic urban design—grids, drains, wells, reservoirs—with exacting measurement, versatile crafts, and maritime networks to sustain some of the Bronze Age’s largest cities. Even without deciphered texts, its bricks, beads, and bones attest to a civic imagination that prized hygiene, standardization, and coordination, shaping South Asia’s urban ethos long after the great cities fell silent.