Introduction

The Gupta period (c. 320–550 CE) is remembered as a classical high point of ancient India, when political consolidation, economic surplus, and royal patronage enabled striking advances in literature, science, mathematics, art, and architecture, even as debates persist about how “golden” it was for all social strata. From Kālidāsa’s Sanskrit masterpieces and Ajanta’s luminous murals to Aryabhata’s astronomical insights and the Gupta mint’s glittering coinage, this era shaped a civilizational canon whose influence radiated across Asia.

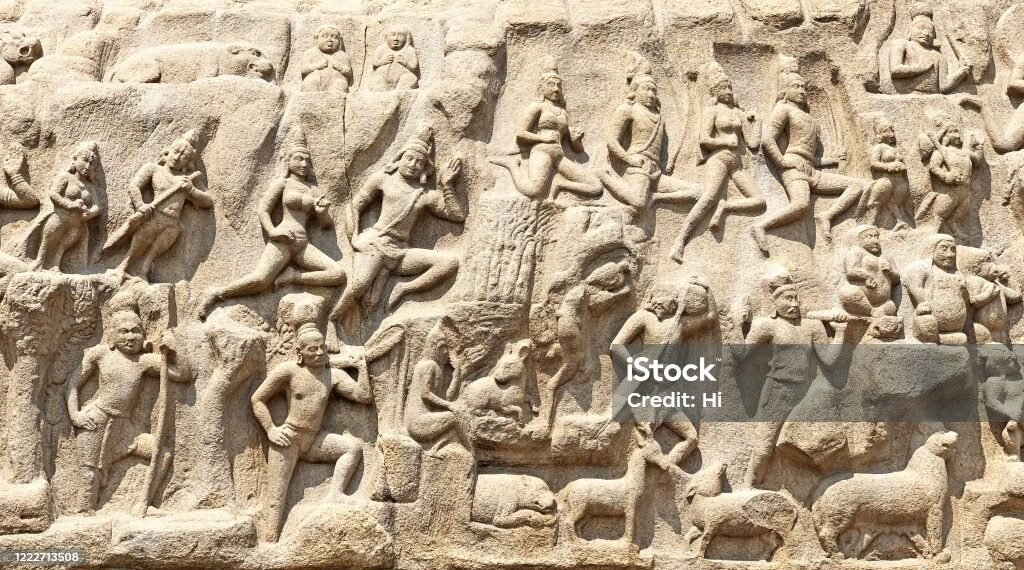

Context and origins

Emerging in the Gangetic heartland after Kushan and Satavahana decline, the Guptas unified much of northern India under rulers like Samudragupta and Chandragupta II, whose campaigns stabilized core territories and secured trade routes. Political stability and courtly patronage fostered cultural efflorescence—Sanskrit became the primary language of high culture, and a distinct Gupta aesthetic matured in sculpture, painting, and temple design.

Key features and vocabulary

Golden Age: A retrospective label emphasizing apex achievements in arts and sciences alongside relative political cohesion and economic prosperity.

Sanskrit cosmopolis: Courtly Sanskrit literature, drama, grammar, and lexicography flourished, canonizing texts and styles that travelled widely.

Court-and-guild economy: Gold and silver coinage, artisan guilds, and land grants to Brahmins/temples coexisted with shifting urban–rural dynamics.

Polity and economy

Administration and land: Inscriptions indicate land classification, surveys, and record-keeping (e.g., Pahadpur copper plate, Poona plates), with officers like the pustapala maintaining transactional archives; land was grouped as cultivable, waste, habitable, pasture, and forest.

Taxation and grants: The crown’s share generally ranged from one‑sixth to one‑fourth of produce; specific levies such as uparikara, udranga, vata‑bhuta, and halirakara appear in sources; widening Brahmana/devagrahara land grants converted virgin tracts to fields but also empowered local grantees.

Coinage and trade: The Guptas issued prolific gold dinars (and regional silver), signaling surplus and court largesse, though gold purity lagged Kushans; long-distance trade with the Roman world waned by the sixth century as routes shifted and silk knowledge diffused, affecting bullion inflows.

Public works: State attention to irrigation and agrarian productivity is noted (e.g., Junagadh inscription on Sudarshana Lake maintenance under Skandagupta), suggesting active stewardship of agriculture—the fiscal backbone.

Science and mathematics

Aryabhata: Advanced a rotating Earth, refined eclipse theory as astronomical (not mythic), worked with sine tables, and contributed to place-value/decimal practice and approximations of π—breakthroughs recorded in influential treatises.

Varāhamihira and others: Texts like Pañca‑siddhāntikā and Bṛhat‑saṁhitā range from astronomy and meteorology to materials, architecture, and omens, evidencing synthetic, applied knowledge traditions.

Medicine and metallurgy: Medical compendia and surgical traditions persisted; the era’s metallurgical skill is reflected in celebrated works and enduring iron craftsmanship, later romanticized for corrosion resistance.

Literature and language

Kālidāsa: The crown jewel of classical Sanskrit—plays (Abhijñānaśākuntalam, Vikramorvaśīyam, Mālavikāgnimitram), mahākāvyas (Raghuvaṁśam, Kumārasambhavam), and lyric (Meghadūta, Ṛtusaṁhāra)—marrying shṛṅgāra rasa with courtly polish.

Court and didactic genres: Amara’s lexicon (Amarakosha), prose/poetry by Harisena (Allahabad prashasti), Viśākhadatta’s Mudrārākṣasa, and the crystallization of smṛti/legal and purāṇic corpora expanded textual ecologies.

Sanskritization: Patronage accelerated Sanskrit’s primacy for elite discourse as Prakrit/Pali receded in prestige, shaping a pan-regional idiom of power and culture.

Art and architecture

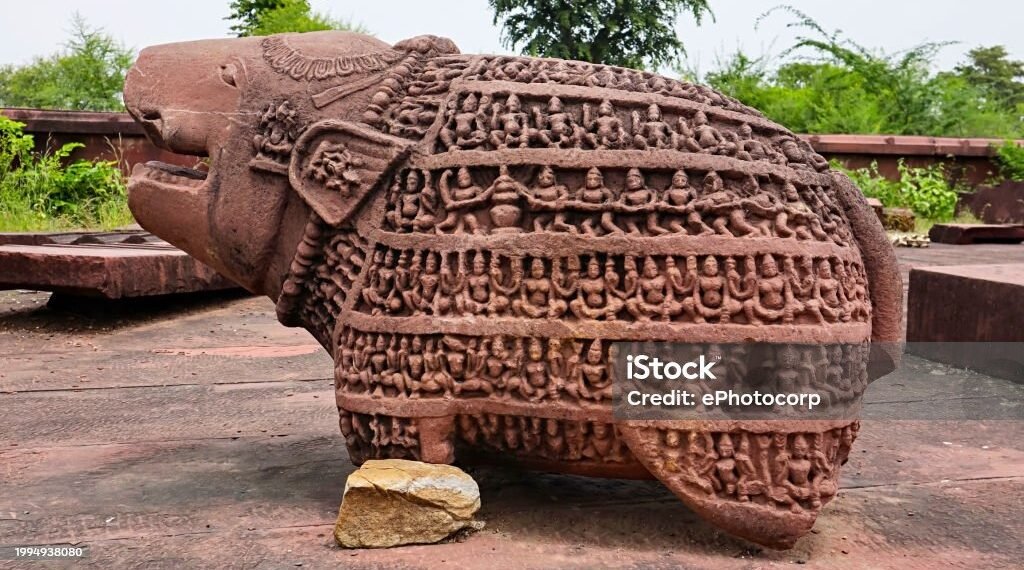

Sculpture: Gupta style balanced idealized form with spiritual poise—Sarnath and Mathura schools produced icons of refined physiognomy and drapery; copper and stone masterpieces reveal technical and aesthetic maturity.

Painting: Ajanta murals achieved narrative grace, color fastness, and anatomical subtlety, depicting Jataka tales and courtly life with rhythmic line and modeling; their technique (fresco‑like tempera) showcases artisanal virtuosity.

Temples: Early structural Hindu temples (e.g., Deogarh’s Dashavatara) model sanctum (garbhagriha) and emergent shikhara forms, laying foundations for later Nagara idioms in North India.

Social textures and debates

Prosperity and inequities: While elite arts and sciences peaked, inscriptions also record vishti (forced labor) and increasing obligations on villages; expanding land grants created “administrative pockets” of grantee authority, complicating peasant rights.

Gender and custom: Later narratives and epigraphs hint at practices like sati emerging in elite strata; scholars debate extent and causality, cautioning against treating the age as uniformly “golden” in social terms.

Urban change: Some northern towns declined amid trade shifts and Huna disruptions; artisan guilds adapted through migration (e.g., silk weavers of Lata to Mandsor), illustrating resilience and reconfiguration of labor.

Why “Golden Age”—and its limits

The case for: Exceptional output in Sanskrit letters, visual arts, mathematics/astronomy; abundant coinage; architectural prototypes; and a stable court culture that exported aesthetics to wider Asia.

The caveats: Uneven welfare, heavier land impositions in places, elite-centric patronage, and late‑period shocks (Huna incursions, bullion scarcity) that undercut commercial vibrancy and foreshadowed fragmentation.

How to read the Gupta legacy today

Canon and curricula: Kālidāsa’s poetics, Ajanta’s pedagogy-in-pigment, and Aryabhata’s math form a triad still foundational to Indian humanities and STEM history.

State and society: Land‑grant regimes and guild philanthropy model state–civil linkages that shaped subcontinental agrarian and temple economies for centuries.

Aesthetic templates: Gupta sculpture’s serene physiognomies and early Nagara temples seeded iconographic and architectural lineages across North India and beyond.

Conclusion

The Gupta centuries condensed a rare alignment—courtly peace, surplus, and patronage—into a civilizational syllabus of literature, science, and art that outlived the dynasty itself. Calling it a “Golden Age” makes sense for canons and craft, but the era’s own inscriptions remind that radiance coexisted with strain: land exactions, coerced labor, and late‑period shocks. The enduring lesson is twofold: cultural peaks need stable institutions and surplus—and a critical gaze to ask whose prosperity made the gold gleam.