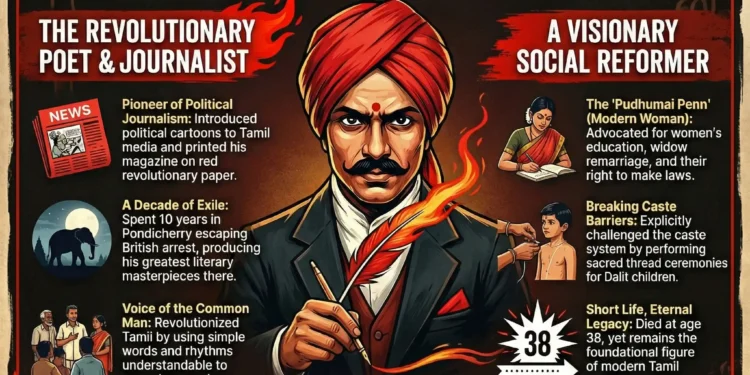

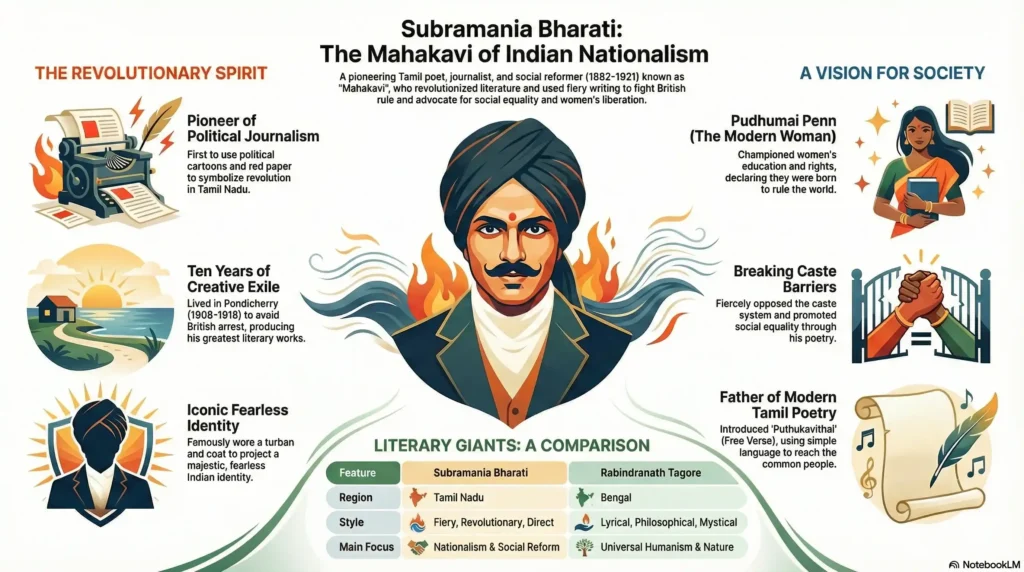

Subramania Bharati (1882–1921), popularly known as Mahakavi Bharathiyar, was a Tamil writer, poet, journalist, and Indian independence activist. Born in Ettayapuram, he was a prodigy who earned the title "Bharati" (Blessed by Saraswati) at age 11. He was a pioneer of modern Tamil poetry, introducing a new style called Puthukavithai (Free Verse). As a journalist, he edited magazines like India and Swadesamitran, using cartoons and fiery editorials to attack British rule. Forced into exile in Pondicherry (then under French rule) for 10 years, he produced his greatest literary works there, including Kuyil Pattu, Kannan Pattu, and Panchali Sabatham. He was not just a nationalist but a social reformer who fought against the caste system and advocated for women's liberation.| Feature | Details |

| Birth Name | Chinnaswami Subramania Iyer |

| Born | December 11, 1882 (Ettayapuram, Tamil Nadu) |

| Died | September 11, 1921 (Madras/Chennai) |

| Title | Mahakavi (Great Poet), Bharathiyar |

| Key Journals | Swadesamitran, India, Vijaya, Bala Bharata |

| Famous Works | Panchali Sabatham, Kuyil Pattu, Kannan Pattu |

| Themes | Nationalism, Women’s Rights, Casteless Society, Nature |

| Exile Location | Pondicherry (1908–1918) |

| Spouse | Chellamma |

The Prodigy of Ettayapuram

Born into a Brahmin family, Bharati lost his mother at age 5 and his father at age 16. Despite these tragedies, his genius shone early. At the age of 11, he won a debate against learned scholars at the court of the Raja of Ettayapuram, earning the title Bharati (one blessed by the Goddess of Learning). He mastered Tamil, Sanskrit, Hindi, French, and English.

Vedic Period 1500-500 BCE: The Foundation of Indian Civilization

The Journalist and Revolutionary

Bharati was not an armchair poet; he was a revolutionary.

- Sister Nivedita: In 1905, he met Sister Nivedita (disciple of Swami Vivekananda) in Calcutta. She inspired him to fight for the freedom of women and the nation. He considered her his Guru.

- Journalism: He joined the Tamil daily Swadesamitran in 1904. Later, he edited the weekly magazine India, which was the first paper in Tamil Nadu to publish political cartoons. He printed it on red paper to symbolize revolution.

- Exile in Pondicherry: Faced with an arrest warrant by the British in 1908, he escaped to Pondicherry (a French colony). He lived there for 10 years, interacting with other revolutionaries like Sri Aurobindo and V.V.S. Aiyar.

Literary Masterpieces

His years in exile were his most creative. He revolutionized Tamil literature by using simple words and rhythm (Sandham) that common people could understand.

- Panchali Sabatham (The Vow of Draupadi): An epic poem where he reinterpreted the Mahabharata. He visualized Draupadi as Mother India, the Pandavas as Indians, and the Kauravas as the British. It was a call to arms for the nation.

- Kuyil Pattu (The Song of the Cuckoo): A romantic and philosophical narrative poem about a poet’s love for a cuckoo bird.

- Kannan Pattu (Songs of Krishna): A collection of devotional songs where he sees Lord Krishna in various roles—as a friend, mother, servant, king, and lover.

- Swadeshi Geethangal: A collection of patriotic songs like “Achamillai Achamillai” (Fearless, Fearless) and “Vande Mataram” (translated/adapted) that became anthems of the freedom movement.

Reign of Emperor Ashoka: The Transformation of a Tyrant

Social Reformer: A Vision Ahead of Time

Bharati was a fierce critic of social evils.

- Women’s Rights: He coined the term Pudhumai Penn (Modern Woman). He wrote, “Pattangal aalvathum sattangal seivathum parinil pengal nadatha vanthom” (We have come to rule the world and make laws). He advocated for women’s education and widow remarriage.

- Caste System: He famously sang, “Jathigal illaiyadi pappa” (There are no castes, my child). He even performed the Upanayana (thread ceremony) for a Dalit boy to prove that caste is not by birth.

The Tragic End

In 1918, Bharati left Pondicherry and was immediately arrested by the British. Although released later, his health had deteriorated due to poverty and imprisonment. In 1921, while visiting the Parthasarathy Temple in Chennai, he was struck by the temple elephant, whom he used to feed regularly. Although he survived the initial injury, his weakened body succumbed to illness a few months later. He died at the young age of 38, leaving behind a legacy that would inspire generations.

Dadasaheb Phalke: The Father of Indian Cinema

Quick Comparison Table: Bharati vs. Tagore

| Feature | Subramania Bharati | Rabindranath Tagore |

| Region | Tamil Nadu | Bengal |

| Title | Mahakavi (Great Poet) | Gurudev (Divine Teacher) |

| Style | Fiery, Revolutionary, Direct | Lyrical, Philosophical, Mystical |

| Focus | Nationalism, Social Reform | Universal Humanism, Nature |

| Key Song | Achamillai Achamillai | Jana Gana Mana |

| Nobel Prize | No | Yes (1913) |

Curious Indian: Fast Facts

- The Turban: Bharati famously wore a turban and a coat, inspired by his admiration for Sikhs and his desire to project a majestic, fearless Indian identity.

- Posthumous Fame: At his funeral, only 14 people were present. His true greatness was recognized only after his death, especially when his songs were used in films and freedom rallies.

- Translation: He translated the Bhagavad Gita and speeches of Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Sri Aurobindo into Tamil.

- First Cartoonist: He is credited with introducing political cartoons to Tamil journalism through his magazine India.

Conclusion

Subramania Bharati was a storm that swept through Tamil Nadu. He took the Tamil language out of ancient scholarship and gave it to the streets. He taught a colonized people to hold their heads high and declared that freedom was the very breath of life. Though he lived a short life of poverty, he left behind a wealth of words that continue to ignite the fire of patriotism and equality.

Sunayani Devi: A Woman’s Voice in the Bengal School

If you think you have remembered everything about this topic take this QUIZ

Results

#1. At what age did Chinnaswami Subramania Iyer earn the title “Bharati” (Blessed by Saraswati) after winning a debate?

#2. Whom did Subramania Bharati consider his Guru, inspiring him to fight for the freedom of women and the nation?

#3. Bharati is credited with introducing political cartoons to Tamil journalism through which weekly magazine?

#4. To escape an arrest warrant by the British in 1908, Bharati lived in exile for 10 years in which French colony?

#5. In his epic poem Panchali Sabatham, whom did Bharati visualize as Mother India to inspire the nation?

#6. What Tamil term did Bharati coin to advocate for women’s rights, education, and liberation?

#7. Which tragic incident contributed to the deterioration of Bharati’s health and his eventual death in 1921?

#8. Bharati famously wore a turban and a coat to project a majestic, fearless Indian identity, inspired by his admiration for which community?

Sangam Period: The Golden Age of Tamil Literature

What is the popular title of Subramania Bharati?

He is called Mahakavi (Great Poet) or Bharathiyar.

Which poem depicts Draupadi as Mother India?

Panchali Sabatham (The Vow of Draupadi).

Where did Bharati live in exile?

He lived in Pondicherry for 10 years (1908–1918).

Who was Bharati’s spiritual guru?

Sister Nivedita (disciple of Swami Vivekananda).

What was the name of the magazine edited by Bharati?

He edited India (a weekly) and worked for Swadesamitran (a daily).