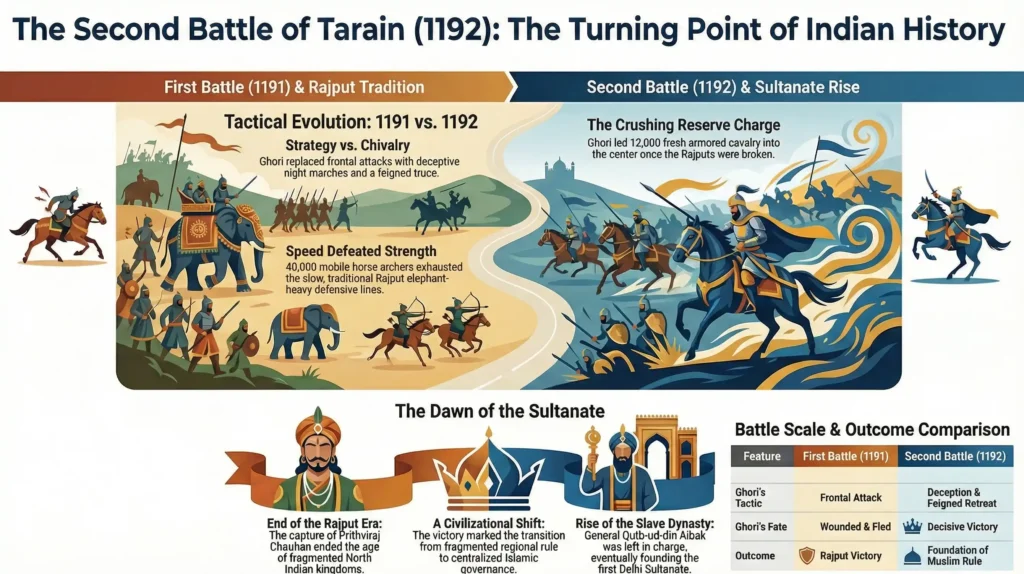

The Second Battle of Tarain was fought in 1192 AD between the Ghurid army of Muhammad Ghori (Mu'izz ad-Din Muhammad) and the Rajput confederacy led by Prithviraj Chauhan (Prithviraj III). Fought on the same battlefield as the First Battle of Tarain (where Ghori was defeated a year earlier), this battle saw a complete reversal of fortunes. Ghori used deceptive tactics, a night march, and horse-archers to exhaust the Rajput army before launching a decisive cavalry charge. Prithviraj Chauhan was captured and executed (or killed in captivity), marking the end of Rajput dominance in North India and paving the way for the Delhi Sultanate.| Feature | Details |

| Date | 1192 AD |

| Location | Tarain (modern Taraori, Haryana) |

| Ghurid Leader | Muhammad Ghori |

| Rajput Leader | Prithviraj Chauhan (Prithviraj III) |

| Ghurid Strength | ~52,000 Cavalry (Divided into 5 divisions) |

| Rajput Strength | ~100,000 Infantry + 300 Elephants (Traditional estimates) |

| Key Tactic | Feigned Retreat & Reserve Charge |

| Outcome | Decisive Ghurid Victory |

| Result | Foundation of Muslim Rule in India |

The Prelude: Revenge for 1191

In 1191, at the First Battle of Tarain, Prithviraj Chauhan had decisively defeated Muhammad Ghori. Ghori was wounded and barely escaped with his life. Instead of chasing the fleeing Ghurid army out of India, Prithviraj allowed them to retreat—a chivalrous mistake that cost him his kingdom.

Humiliated, Ghori returned to Ghazni and spent a year rebuilding his army. He dismissed his lazy commanders, recruited 120,000 select Afghan and Turkic horsemen, and marched back to India with a single-minded focus: revenge.

Timur’s Invasion of Delhi 1398: The Massacre That Shook India

The Deception

When Ghori reached Lahore, he sent a letter to Prithviraj demanding submission. Prithviraj replied with a defiant counter-offer: “Retreat now and I won’t destroy you.”

Ghori played a cunning game. He replied, “I must ask my brother in Ghazni for permission to retreat.” This lulled the Rajputs into a false sense of security. They believed a truce was in place and relaxed their guard.

Reign of Alauddin Khalji 1296-1316: The Iron Fist of Delhi

The Battle: Dawn of Doom

On the morning of the battle, Ghori launched a surprise attack before dawn while the Rajput soldiers were performing their morning ablutions. Though shaken, the Rajput army formed their traditional defensive line with elephants in front.

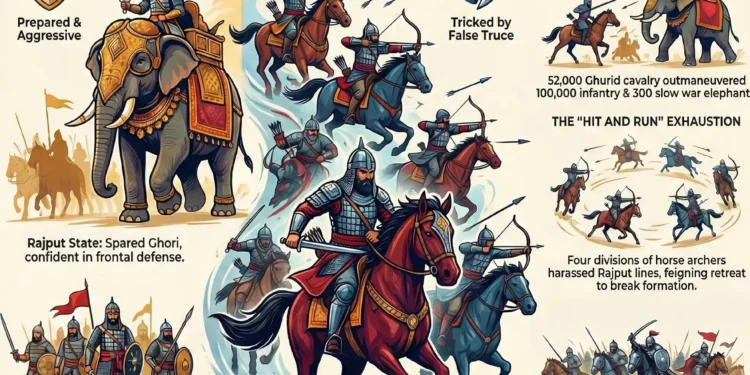

Ghori knew he couldn’t face the elephants head-on. He divided his army into five divisions:

- Four Divisions (10,000 archers each): Their job was to harass the Rajputs from four sides. They would ride close, shoot arrows, and then feign retreat when the Rajputs charged. This “hit and run” tactic exhausted the heavy Rajput armor and elephants.

- Fifth Division (12,000 armored cavalry): This was the reserve force, commanded by Ghori himself.

The Turning Point

By the afternoon, the Rajput soldiers were tired, thirsty, and frustrated by chasing the elusive horse archers. Their formation was broken. Sensing the moment, Muhammad Ghori led his 12,000 fresh armored heavy cavalry in a crushing charge into the center of the Rajput line.

The tired Rajput infantry couldn’t withstand the shock. The elephants panicked. Prithviraj Chauhan tried to escape on a horse but was captured near the river Saraswati (Sirsa).

The End of Prithviraj

Historical accounts vary on Prithviraj’s fate:

- Persian Sources: State he was captured and executed immediately.

- Prithviraj Raso (Epic Poem): claims he was taken to Ghazni, blinded, and then killed Ghori with an arrow guided only by sound (Shabd Bhedi Baan), before killing himself.Most historians agree he was likely executed shortly after the battle.

First Battle of Panipat 1526: The Dawn of the Mughal Empire

Quick Comparison Table: First vs. Second Battle of Tarain

| Feature | First Battle of Tarain (1191) | Second Battle of Tarain (1192) |

| Ghurid Strategy | Frontal Attack | Feigned Retreat & Surprise |

| Rajput State | Prepared & Aggressive | Complacent (Tricked by truce) |

| Ghori’s Fate | Wounded & Fled | Victorious |

| Prithviraj’s Fate | Victorious (Let enemy escape) | Captured & Killed |

| Outcome | Rajput Victory | Islamic Conquest of India |

Curious Indian: Fast Facts

- The Traitor? Popular folklore blames Jaichand of Kannauj for betraying Prithviraj due to the abduction of his daughter Sanyogita. While Jaichand didn’t help Prithviraj, there is no historical proof he actively joined Ghori in 1192. He was defeated by Ghori later in the Battle of Chandawar (1194).

- Qutb-ud-din Aibak: This battle made the career of Ghori’s slave-general, Qutb-ud-din Aibak, who was left in charge of India and later founded the Slave Dynasty.

- Tactical Shift: This battle proved the superiority of the Turkish mobile cavalry over the slow-moving Indian war elephants. Speed defeated strength.

Conclusion

The Second Battle of Tarain was not just a military defeat; it was a civilizational shift. It ended the era of fragmented Rajput kingdoms and began the era of centralized Muslim rule under the Delhi Sultanate. It taught a brutal lesson in warfare: chivalry has no place on the battlefield; only strategy survives.

Establishment of the Delhi Sultanate: The Five Dynasties That Ruled India

If you think you have remembered everything about this topic take this QUIZ

Results

#1. In which year was the decisive Second Battle of Tarain fought?

#2. Who were the two opposing leaders in the Second Battle of Tarain?

#3. What “chivalrous mistake” did Prithviraj Chauhan make after the First Battle of Tarain in 1191?

#4. What deceptive tactic did Muhammad Ghori use to lull the Rajputs into a false sense of security before the battle?

#5. Which military tactic proved decisive for the Ghurid army against the Rajput elephants and infantry?

#6. The Second Battle of Tarain is historically significant because it paved the way for:

#7. According to historical accounts, what was the fate of Prithviraj Chauhan after the battle?

#8. How did the Rajput army’s preparation differ in 1192 compared to 1191?

When was the Second Battle of Tarain fought?

It was fought in 1192 AD.

Who won the Second Battle of Tarain?

Muhammad Ghori (Ghurid Dynasty) won the battle.

Who was the Rajput king defeated in this battle?

Prithviraj Chauhan (Prithviraj III) was defeated.

What was the main reason for Prithviraj’s defeat?

Ghori’s deceptive tactics (surprise dawn attack and feigned retreat), combined with the Rajput army’s exhaustion and lack of mobility.

What happened after the battle?

Prithviraj was captured and killed. Muhammad Ghori appointed Qutb-ud-din Aibak as his governor, leading to the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate.