Introduction

In the 6th century BCE, intense social, political, and economic churn across the Gangetic plain produced a family of śramaṇa movements, of which Jainism and Buddhism became pre‑eminent alternatives to Vedic orthodoxy, rejecting sacrificial ritualism, challenging birth‑based privilege, and offering accessible ethics and paths to liberation in the vernaculars.

Why they arose then

Social strain and ritual fatigue: Elaborate sacrifices monopolized by Brahmins, coupled with philosophical abstraction in late Vedic thought, alienated many householders who desired a simpler, ethical religion focused on conduct rather than costly rites.

Urbanization and new classes: Iron‑led agrarian expansion and trade birthed towns, caravan routes, and wealthy guilds; prosperous Vaishyas sought dignity beyond ritual ranking and funded mendicant teachers with universalist ethics.

Language and access: Preaching in Pali/Prakrit rather than Sanskrit brought teachings to craftspeople, peasants, and merchants, widening reach and lowering barriers to entry.

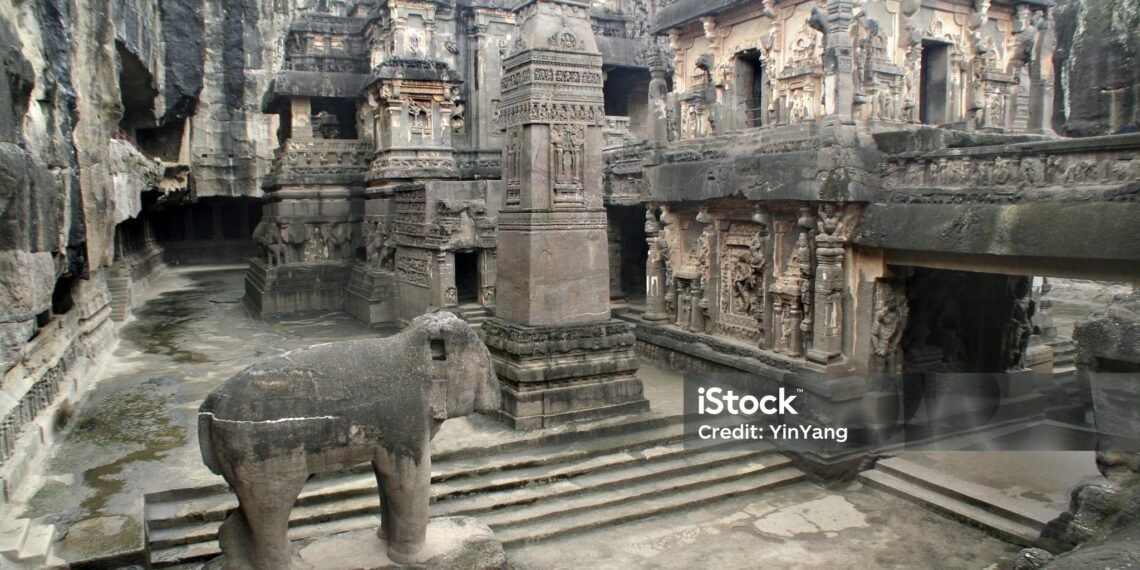

Inside the Ellora Caves in Maharashtra State, India. A series of Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain temples and monasteries carved out of basalt rock

Jainism in brief

Teacher and lineage: Vardhamana Mahavira, the 24th Tirthankara, codified an ancient lineage emphasizing extreme ahimsa and self‑conquest; Jain memory casts him as a reformer who distilled rigorous vows for lay and monastic life.

Core ethic: The five mahāvratas—non‑violence, truth, non‑stealing, celibacy, and non‑possession—apply absolutely to monks and in moderated forms to laity, with meticulous care to avoid harm to all life forms.

Doctrine: Belief in eternal jīva (soul), karma as matter that binds the soul, and liberation (moksha) through austerity, right knowledge, and right conduct; anekāntavāda and syādvāda articulate plural viewpoints and conditional predication.

Buddhism in brief

Turning points: Siddhartha’s Four Sights—old age, sickness, death, and a renunciant—triggered his quest; enlightenment at Bodh Gaya and the first sermon at Sarnath set the Dharma in motion for a wandering fellowship.

Core teaching: The Four Noble Truths diagnose suffering and its causes; the Noble Eightfold Path prescribes ethical, meditative, and wisdom disciplines as the Middle Way between sensuality and self‑mortification.

Community and spread: Early patrons included Bimbisara, Ajatashatru, and other Gangetic rulers; sangha organization, lay support, and later Ashokan endorsement enabled inter‑regional missions and durable institutionalization.

Shared ground and sharp differences

Shared: Non‑violence, karma, rebirth, monastic–lay synergy, rejection of costly sacrifices and hereditary ritual privilege, and preference for vernacular preaching made both movements compelling civic religions.

Differences: Buddhism denies a permanent self (anattā) and emphasizes intent with a calibrated ethic under the Middle Way; Jainism upholds an eternal soul and applies ahimsa and celibacy with maximal rigor, especially in monastic codes.

Social and political reception

Merchant embrace: Guilds and caravan leaders found practical value in honesty, restraint, and non‑violence—norms that stabilized contracts and reputations—driving endowments to monasteries and Jain sanghas.

State calculus: Mahajanapada rulers valued teachers who tempered violence and legitimated rule through dharma; court patronage provided land grants, vihāras, and legal recognition without enforcing doctrinal monopoly.

Intellectual and ethical innovations

From rite to ethics: Both traditions redirected aspiration from sacrificial entitlement to ethical universals—right speech, livelihood, truth, compassion—shifting religion toward personal responsibility and civic virtue.

Method and debate: Dialogues with Brahmanical thinkers and other śramaṇas normalized public disputation; Jain anekāntavāda fostered epistemic humility, while Buddhist dependent origination reframed causality beyond ritual determinism.

Why they endured

Institutional design: Monastic codes, lay precepts, periodic confession, rains‑retreat calendars, and donation merit created sustainable rhythms of teaching, travel, and support.

Portability: Clear ethical canons and congregational practices traveled easily across trade routes, enabling replication from the Ganga plain to Deccan towns and, for Buddhism, beyond India.

High‑yield contrasts for study

Self/soul: Buddhism—no eternal self (anattā); Jainism—eternal soul (jīva).

Path: Buddhism—Middle Way via Eightfold Path; Jainism—ascetic purification via the Three Jewels (right faith, knowledge, conduct) and five vows.

Ahimsa: Buddhism—intention‑sensitive non‑violence; Jainism—absolute and meticulous non‑harm.

Sources: Buddhism—Tripiṭaka corpus; Jainism—Agamas and commentarial traditions in Ardhamagadhi/Prakrit and Sanskrit.

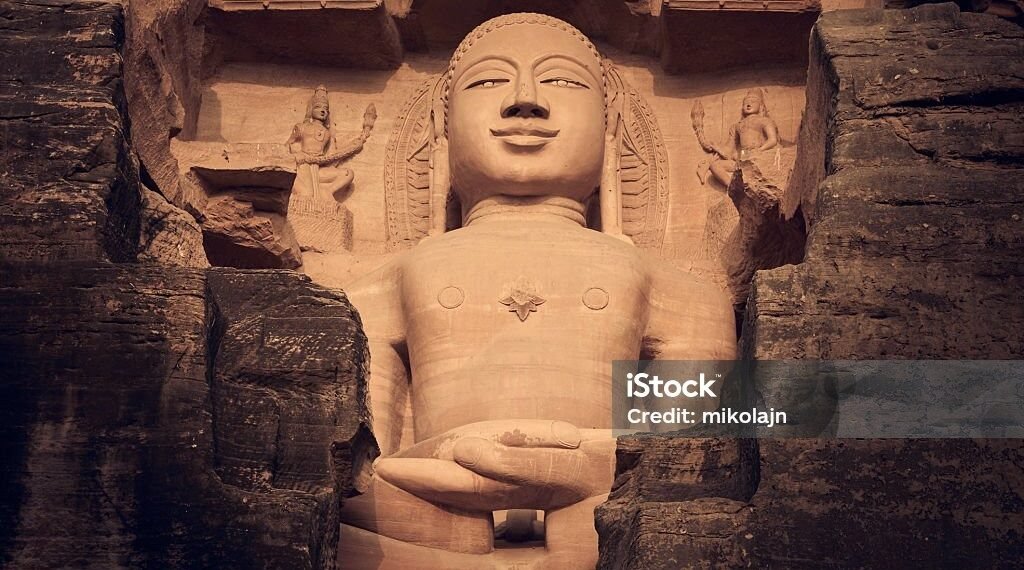

Gopachal Rock Cut Digambar Jain Statues in Gwalior city, India

Conclusion

Jainism and Buddhism rose as practical revolutions in ethics, language, and authority during an age of iron, cities, and states—translating metaphysical aspiration into an everyday discipline of non‑harm, truth, and mindful livelihood. In displacing sacrifice with conscience and caste with conduct, they reimagined religion as a public good suited to a changing society—and built institutions resilient enough to carry that imagination across regions and centuries.