Introduction

Samudragupta (c. 335–375 CE) expanded a Gupta heartland into a northern empire through sequential campaigns recorded in the Prayaga‑Prashasti, celebrated his sovereignty with the Ashvamedha, and left a rich gold coinage that portrays him as conqueror, donor, and veena‑playing “Kaviraja.”

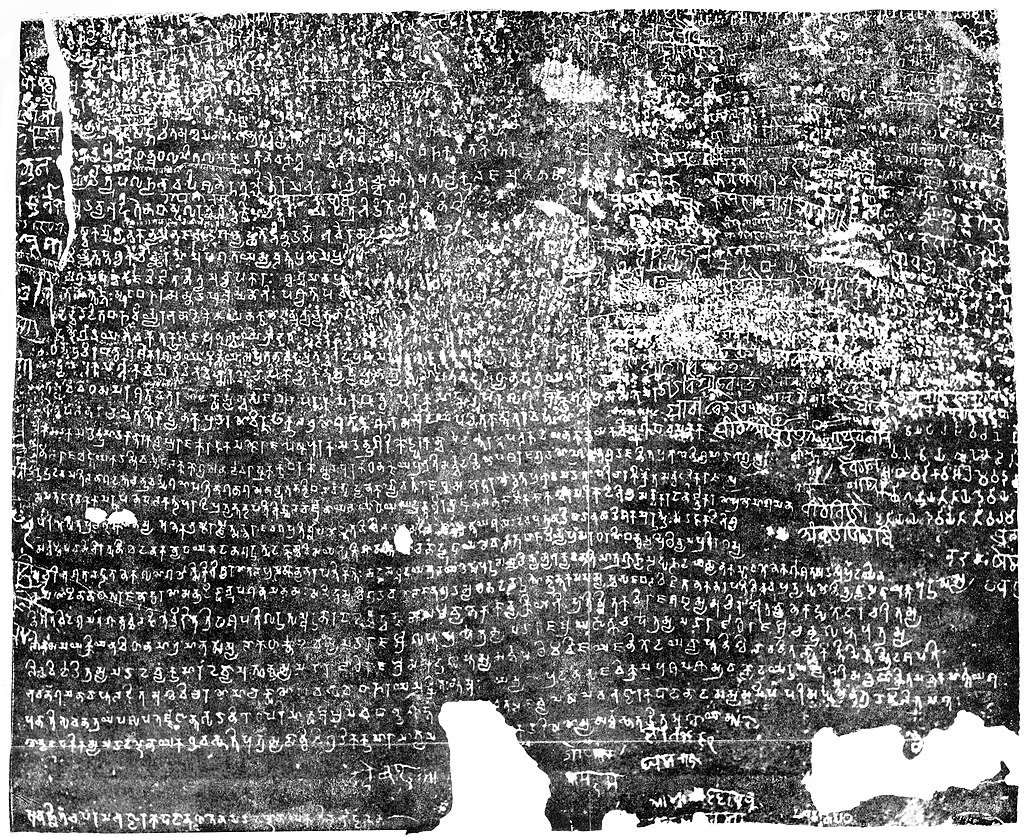

Sources and inscription

The principal source is Harisena’s Sanskrit panegyric on the Allahabad Pillar (Prayaga‑Prashasti), engraved below Ashoka’s earlier edicts, detailing Samudragupta’s enemies, policies toward different regions, and imperial ideology. Later notices and coin legends corroborate the Ashvamedha and titles, while foreign references note exchanges with Sri Lanka’s king Meghavarman.

Conquest strategy

Aryavarta annexations: Northern kings such as Achyuta, Nagasena, and Ganapati‑Naga were “uprooted,” with their territories incorporated into direct rule across the Ganga‑Yamuna heartland and adjoining tracts.

Forest kingdoms: Atavika chiefs in central Indian highlands were reduced to subordination, consolidating the middle corridor from the Doab toward the Vindhyas.

Dakshinapatha policy: Twelve southern rulers from Kanchi, Vengi, Pishtapura, Avamukta and others were captured and released, restored as tributaries rather than annexed—a pragmatic blend of prestige and logistical realism.

Frontier polities: Later Kushanas, Shakas, and border chiefs acknowledged suzerainty, rendering service and tribute and seeking the Gupta garuda seal for administration, indicating layered overlordship beyond the core.

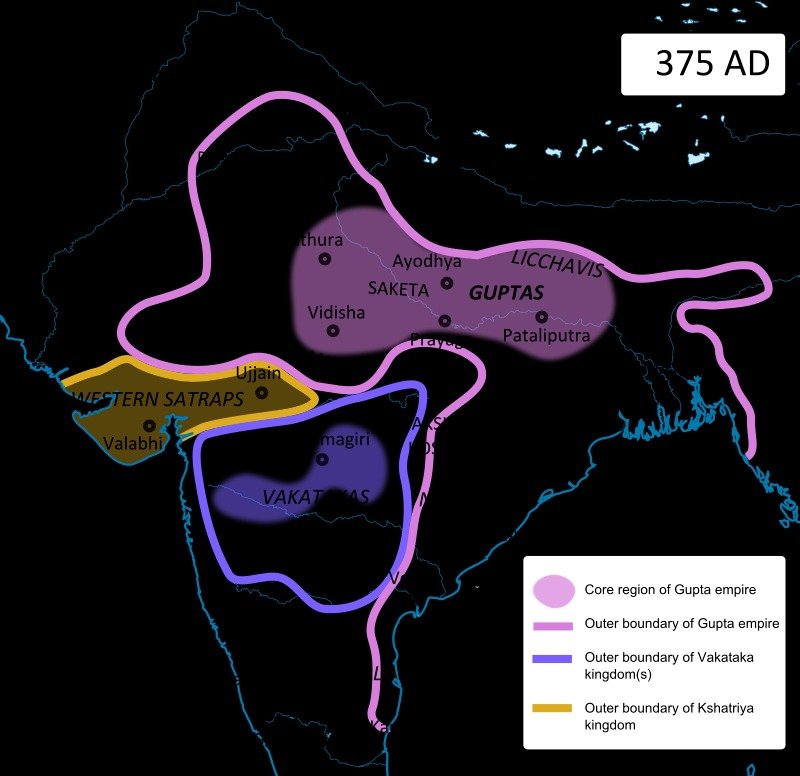

Territorial footprint

By the late reign, direct control spanned most of the Ganga valley, parts of central India, and the Bengal–Assam arc, while tributary ties radiated to the eastern coast and the northwest; Kashmir, western Punjab, Rajasthan, Sindh, and Gujarat lay largely beyond annexed core but within varying spheres of influence.

Ashvamedha and coinage

Samudragupta revived the Ashvamedha to proclaim paramountcy and issued special gold types marking the rite; broader gold series include Garuda, Archer (Dhanurdhara), Ashvamedha, Vyaghra‑nihanta, Parashurama, and Veena‑vadana, the last depicting him as a cultured monarch and “Kaviraja.”

Diplomacy and religion

Chinese accounts preserve that Sri Lanka’s Meghavarman sought and obtained permission to build a monastery at Bodh Gaya, evidence of diplomatic stature and Buddhist institutional patronage within a predominantly Vaishnava court culture. The Bodh Gaya epigraphic tradition ties this Sri Lankan endowment to Gupta‑era royal consent.

Governance cues

The inscription notes rulers “rendering service,” seeking use of the imperial seal, and entering alliances, implying a spectrum from annexed districts to autonomies under Gupta sanction; this mixed constitution foreshadows samanta dynamics under later Guptas.

Reputation and titles

Victorious across multiple theatres and never recorded as defeated, Samudragupta was styled Maharajadhiraja and praised as the “Napoleon of India” by modern historians; his own eulogy casts him as both war‑leader and patron of music and letters.

High‑yield anchors

Inscription: Prayaga‑Prashasti by Harisena on the Allahabad pillar.

Campaign blocks: Aryavarta annexed; Atavika subdued; Dakshinapatha captured‑and‑released as tributaries; frontier polities submit.

Coins and rites: Ashvamedha performance; Veena‑vadana, Archer, Garuda, and other gold types.

Foreign link: Sri Lankan monastery at Bodh Gaya authorized for Meghavarman.

Text of the Allahabad stone pillar inscription of Samudragupta | Source: Wikipedia

Conclusion

By coupling hard annexations in the north with tributary diplomacy south and west, proclaiming sovereignty through Ashvamedha, and curating a sovereign image in coinage and verse, Samudragupta forged the Gupta imperial grammar—direct rule at the core, layered suzerainty at the margins, and cultural prestige binding both.