Introduction

Akbar the Great, third Mughal emperor, ruled from 1556 to 1605 and transformed the Mughal Empire into one of the largest and most culturally vibrant powers in premodern Indian history. His reign is synonymous with military expansion, administrative innovation, religious tolerance, and a flourishing of art and architecture. Akbar’s legacy remains foundational for understanding South Asian governance, society, and syncretic culture.

Early Years and Consolidation

Akbar ascended the throne at age thirteen after the death of his father Humayun, inheriting an empire at risk from internal instability and external threats. Initial victories such as the Second Battle of Panipat (1556) against Hemu and the suppression of regional rivals (Afghans in Bihar, rebellion in Punjab) consolidated Mughal control, under the guidance of his regent Bairam Khan.

Once free from Bairam Khan’s control, Akbar navigated court politics, sidelined powerful nobles, and focused on territorial expansion and empire-building, setting the stage for the empire’s “golden age”.

Military Expansion and Conquest

Rajput Policy

Akbar’s approach toward Rajput states marked a dramatic shift from previous confrontation to a blend of military campaigns, diplomacy, and matrimony. He subdued recalcitrant rulers (Malwa, Garhkatanga), orchestrated alliances through strategic marriages (e.g., marriage to Harkha Bai), and elevated loyal Rajput chiefs to high ranks in the Mughal nobility. This pragmatism helped unify diverse Indian territories under Mughal suzerainty, except Mewar’s Maharana Pratap whose defiance culminated in the legendary Battle of Haldighati (1576).

Conquest of Gujarat, Bengal, and the Northwest

Akbar’s annexation of Gujarat in 1573 bolstered imperial revenues through control of maritime trade. Bengal was added in 1576 after defeating Daud Khan Karrani, expanding the Mughal presence across eastern India. In the northwest, campaigns subdued Afghanistan’s rebel chiefs and secured frontier provinces, while later efforts in the Deccan (Ahmednagar, Berar, Khandesh) extended Mughal rule toward the southern peninsula.

Military Reforms

Akbar introduced pioneering military technologies such as improved cannons, matchlock muskets (bandook), and strengthened the army via the Mansabdari system—a graded rank system integrating different ethnic groups and ensuring centralized imperial loyalty. These measures professionalized the forces and helped repel external threats and quell internal revolts throughout his reign.

Administrative Innovations

Akbar’s reign is renowned for the consolidation of a robust, centralized bureaucracy. Key administrative reforms included:

Mansabdari System

This ranking system assigned ranks (mansabs) based on both military and civil service, integrating nobles and promoting meritocracy while tying administration directly to the emperor. Civil officers were also given military roles, erasing the “sword-pen” distinction and increasing loyalty to the central authority.

Revenue Reforms

Chief revenue official Raja Todar Mal developed the Dahsala system—a method of land revenue assessment and collection based on detailed surveys, soil fertility, and average crop yields. These reforms increased efficiency, provided stable income for the state, and aimed to reduce the tax burden and corruption experienced by peasant cultivators.

Judicial and Legal Reform

Akbar created an inclusive legal framework, incorporating Islamic law and Hindu court customs to safeguard equality. He abolished discriminatory taxes (such as jizya), promoted common legal practices, and sought advice from scholars of all faiths. The Mahzar decree (1579) established his authority over religious matters and encouraged intellectual dialogue in the imperial court.

Religious Policies and Social Harmony

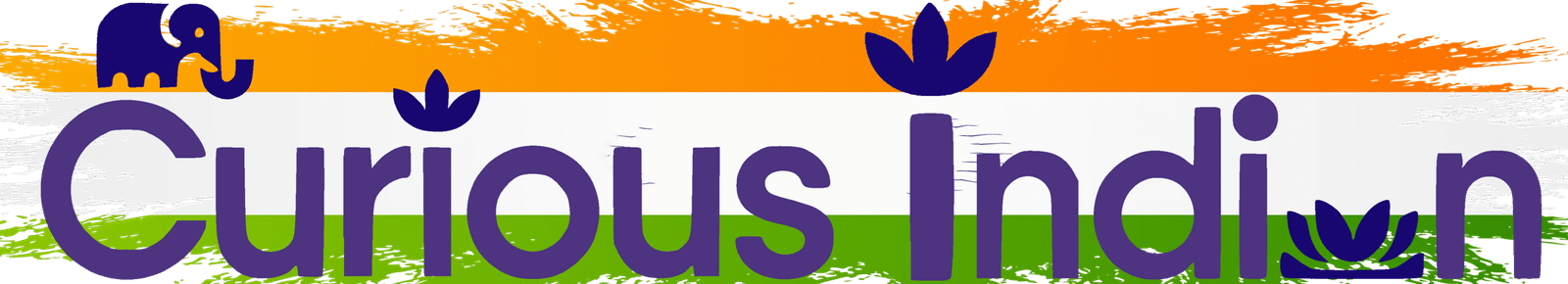

Akbar’s religious vision was transformative for its era. He practiced Sulh-i-Kul (universal peace), advocating for religious tolerance, abolishing the pilgrimage tax and jizya on non-Muslims, and including Hindus and diverse faith groups in his administration. The Ibadat Khana at Fatehpur Sikri became a forum for debate among scholars from multifarious religions, inspiring Akbar to absorb the best elements of every faith.

He supported translations of Hindu texts (Mahabharata, Ramayana) into Persian, commissioned multi-faith debates, and condemned social injustices like sati and infanticide, thus facilitating broader cultural and intellectual exchange.

Din-i-Ilahi

Akbar launched the syncretic Din-i-Ilahi (“Divine Faith”), blending principles from Islam, Hinduism, Christianity, and Zoroastrianism—although it remained limited in adoption and more significant as an emblem of his universalist aspirations than as a mass movement.

Cultural, Artistic, and Economic Flourishing

Akbar’s era is remembered for both material prosperity and a rich cultural efflorescence. Imperial patronage catalyzed the construction of monumental cities like Fatehpur Sikri and architectural masterpieces (Buland Darwaza, Jama Masjid). Persian, Sanskrit, and regional vernacular literatures flourished; miniature painting reached new heights in the Mughal atelier.

Economic growth was stimulated by agricultural reform, textile and silk industries, improved transport, and trade. Markets attracted merchants from Central Asia and Europe, positioning Mughal India as a global center for arts and commerce.

Outcomes, Legacy, and Significance

Akbar’s reign is celebrated as the “golden age” of the Mughal Empire for its political stability, economic prosperity, and creative dynamism.

His policies of conciliation and tolerance integrated India’s pluralistic society, helping the empire endure beyond his lifetime and serving as a model for subsequent rulers.

Centralized reforms established the foundation for later Mughal governance, survived through challenging times, and inspired later administrative systems in South Asia.

Religious innovations—especially Sulh-i-Kul and the abolition of discriminatory practices—set important standards for social harmony.

Akbar’s legacy is reflected in the sustained cosmopolitanism of major cities (Delhi, Agra, Lahore), enduring art forms, and Indian historical memory as a symbol of visionary leadership and syncretism.

Falcon Mohur of Akbar, minted in Asir, issued in the name of Akbar to commemorate the capture of Asirgarh Fort of the on 17 January 1601. | Source: Wikipedia Conclusion

Akbar’s reign stands as a monumental chapter in Indian history, characterized by remarkable military conquests, innovative governance, and a progressive vision of religious and cultural inclusivity. His ability to integrate diverse peoples under a centralized administration while respecting their beliefs and practices created a cohesive empire at a time when religious and regional divisions often threatened unity. The administrative reforms, especially the Mansabdari system and revenue policies, established governance models that endured for centuries and influenced subsequent rulers.