Introduction

Razia Sultan (r. 1236–1240) defied the patriarchal conventions of the 13th-century Delhi Sultanate to rule in her own right as Sultan, not Sultana. Groomed by her father Iltutmish for statecraft, she asserted a merit-based claim to sovereignty, fought down Turkic aristocratic rebellions, built alliances with non-Turk elites, and briefly stabilized the throne before a coalition of nobles unseated her. Though her reign was short, Razia’s political acumen and public leadership etched a lasting place in South Asian memory as the first—and only—woman to sit on Delhi’s throne.

Context and origins

Born around 1205 to Shams al‑Din Iltutmish of the Mamluk (Slave) dynasty, Razia grew up in a court where military talent could trump lineage and where her father himself had risen by merit. After Iltutmish’s capable heir Nasiruddin Mahmud died in 1229, Razia impressed in a regency role during Iltutmish’s Gwalior campaign—reportedly prompting him to designate her as successor for competence over sons he considered frivolous. Yet on Iltutmish’s death (1236), the Turkic nobility installed her brother Rukn al‑Din Firuz. His misrule and the popular confidence Razia commanded soon reversed the tide, and she ascended the throne as Jalalat al‑Din Razia.

Key features and vocabulary

Chahalgani (The Forty): The influential corps of Turkic slave‑amirs whose power over succession and policy Razia confronted from her first days on the throne.

Iqta and amir‑i‑hajib: Provincial revenue assignments (iqta) and high court offices Razia used to re-balance elite power, elevating both Turk and non-Turk nobles according to loyalty and capacity.

Public kingship: Chroniclers note Razia’s court appearances unveiled and in “male” regalia, coinage and khutba in her own name—gestures asserting full sovereign authority rather than consort status.

Accession against the odds

Razia’s initial legitimacy rested less on the Forty than on Delhi’s populace, jurists, and officers disillusioned with Rukn al‑Din. She mobilized popular support dramatically—appealing for justice at Friday congregational prayers in Quwwat‑ul‑Islam, invoking her father’s benevolence and her own administrative record—to catalyze a constitutional pivot in her favor. Once enthroned, she moved swiftly: she confirmed loyalists, redistributed offices, and tempered the Forty’s clout by promoting competent non‑Turks alongside Turks, a strategy that widened her base but intensified aristocratic hostility.

Policy and governance

Consolidation by diplomacy and force: Facing simultaneous revolts (Badaun, Hansi, Multan, Lahore), Razia split rebel coalitions with secret understandings, induced defections, and pursued hardened holdouts until their capture or flight—classic divide‑and‑neutralize statecraft.

Administrative appointments: She elevated figures like Ikhtiyaruddin Aitigin (amir‑i‑hajib) and rewarded provincial governors who stayed loyal, signaling a performance‑based order and the Sultan’s prerogative to make and unmake grandees.

Public order: Expeditions toward Ranthambore and interventions in Lahore and Sirhind aimed to reassert central authority across a still‑fragile sultanate frontier.

Court politics, rumor, and revolt

Razia’s visible favor to select officers—Abyssinian stable‑superintendent Yaqut is frequently named—was weaponized by rivals into slander about impropriety, a gendered trope in premodern and modern politics alike. As she marched to meet a Lahore challenge, Turkic chiefs coordinated an uprising at Tabarhinda (Bhatinda) under Malik Altunia. In the ensuing clash, Yaqut was killed and Razia captured—evidence of how swiftly court alliances could flip under the Forty’s pressure.

The Altunia turn and last campaign

Imprisoned at Tabarhinda, Razia won over her captor Altunia—variously presented as old ally or opportunist—and married him, forging a bid to retake Delhi. The pair advanced on the capital in September 1240, but the nobles had already enthroned Bahram Shah. Razia and Altunia were defeated outside Delhi; fleeing north, they were killed near Kaithal, likely by local bandits.

Reading Razia’s short reign

Merit over pedigree: From Iltutmish’s grooming to Razia’s own promotions, the Mamluk state briefly made capacity the currency of rule, unsettling an oligarchy invested in origin and club power.

Public legitimacy: Razia’s dramatic mosque appeal and her open courtly presence treated sovereignty as a public compact, not private patrimony—unusual and unsettling to entrenched nobles.

Gender and authority: Chroniclers’ fixation on attire and seclusion reveals the frame through which a woman sovereign was judged; Razia’s insistence on Sultan (not Sultana) was a constitutional claim, not a costume.

Legacy and significance

Razia endures as a hinge figure: the Delhi Sultanate’s only woman sovereign, the first to test the limits of a Turkic court elite, and an early exemplar of rule-by-ability against oligarchic privilege. Her defeat did not erase her precedent; it exposed a structural tension between central monarchy and aristocratic caucus that recurred through the Sultanate’s history. In cultural memory, Razia’s image—on coins, in tales, and in feminist retellings—marks a political imagination larger than her years on the throne, where legitimacy could be claimed by service, justice, and nerve.

How to trace Razia today

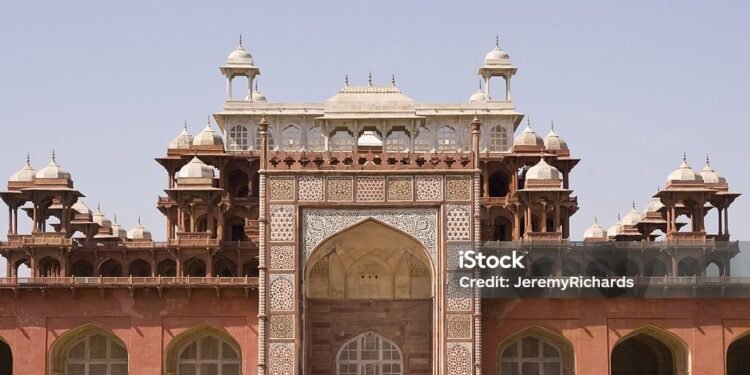

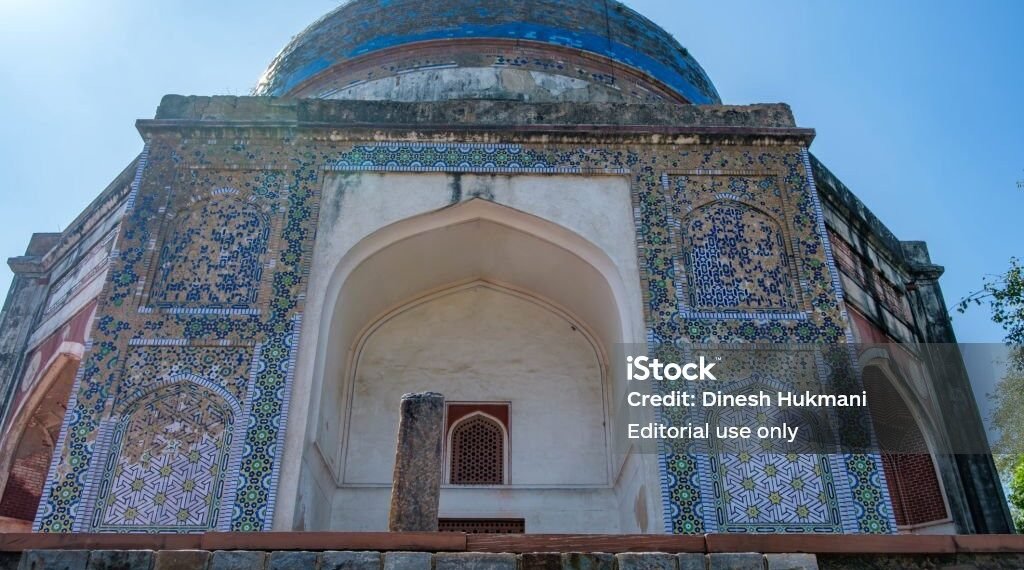

Sites and sources: Qutb complex (Quwwat‑ul‑Islam) as stage of her appeal; Bhatinda (Tabarhinda) as pivot of capture; Kaithal area as the site of her end; read Minhaj‑i‑Siraj alongside modern critical histories for contrasting lenses.

Classroom angles: Razia as case study in succession politics, gendered legitimacy, and the Forty’s oligarchy; compare with later struggles between throne and nobility in other dynasties.

Conclusion

Razia Sultan’s story is not merely that of a woman who ruled; it is the record of a constitutional gamble—asserting that competence and consent could crown a sovereign against aristocratic monopoly. She reconfigured alliances, campaigned in person, legislated merit, and modeled public kingship; and though overborne by the Forty, she proved that Delhi’s throne could, if only briefly, be a woman’s to claim, defend, and dignify.