Introduction

The Rajput age in North and Central India broadly spans the 7th to 12th centuries CE, when the disintegration of Gurjara‑Pratihara authority and the waning of imperial centers produced a mosaic of powerful regional houses across Rajasthan, Gujarat, Malwa, Bundelkhand, Delhi‑Haryana, and the Ganga plains. These kingdoms—Tomaras, Chauhans (Chahamanas), Gahadavalas, Paramaras, Chandelas, Solankis (Chaulukyas), and the Mewar lines (Guhilas → Sisodias)—stabilized frontier zones, fostered temple‑centered urbanism, and patronized vernacular court culture, even while locked in intense inter‑dynastic warfare. Their rise both resisted and redirected external pressures (from Ghaznavids to Ghurids), and their political grammar—forts, feudatories, marriage alliances, and sacrificial titulature—defined much of early‑medieval polity.

Origins and formation debates

Three broad strands explain Rajput formation. One reads them as Kshatriya continuities from earlier Vedic‑Itihasa lineages (e.g., Suryavansha/Chandravansha genealogies claimed by many houses), suggesting status consolidation through political success. A second emphasizes ethnogenesis from Central Asian frontier groups (Śaka‑Kushan‑Huna) that settled in northwestern India across centuries, acquiring Kshatriya standing via service, landholding, and ritual legitimation. A third highlights the fluidity of caste in early‑medieval times—status rising with office, arms, and land—so that martial lineages, whether indigenous or migrant, were absorbed into the Kshatriya ambit through Brahmanical ritual and royal marriage. Whatever the balance, by the 10th–12th centuries distinct dynastic polities had crystallized across key corridors.

Political map and core dynasties

Tomaras (Delhi–Haryana): Emerging as Pratihara subordinates, the Tomaras asserted independence and developed Delhi (Anangpur/Anandapura) as a fortified center; Anangpal Tomar is credited with founding/fortifying Lal Kot near today’s Qutub complex, later expanded by the Chauhans as Qila Rai Pithora.

Chauhans/Chahamanas (Śākambharī–Ajmer–Delhi): Originating around Sambhar (Śākambharī), the Chauhans rose under rulers like Ajayaraja II, shifted the capital to Ajayameru (Ajmer), and expanded toward Delhi; Prithviraj III (Prithviraj Chauhan) became preeminent across Rajasthan–Delhi, defeating neighbors such as the Chandelas at Mahoba before confronting Ghurid expansion at Tarain.

Gahadavalas (Kashi–Kannauj): Centered on Varanasi (and later Kannauj), the Gahadavalas consolidated under Chandradeva and peaked under Govindachandra; later ruler Jayachandra confronted Ghurid pressure after the Chauhan defeat, reflecting the Ganga valley’s contested landscape.

Paramaras (Malwa): From Dhar/Ujjain, Paramaras like Munja and Bhoja I anchored Malwa’s political‑cultural florescence, controlling the plateau routes and contesting with Chalukyas and neighbors.

Chandelas (Bundelkhand): From Khajuraho–Mahoba, the Chandelas built a durable fort‑temple polity, balancing against Chauhans and Pratiharas, and are renowned for the Khajuraho temple complex.

Solankis/Chaulukyas (Gujarat): Based at Anhilwara (Anahilavada‑Patan), the Solankis dominated Gujarat’s trade arteries; queens such as Udayamati commissioned monuments like Rani‑ki‑Vav, and the line managed the Kathiawar‑Cambay corridor.

Mewar lines—Guhilas to Sisodias (southern Rajasthan): The Guhilas (c. 8th–13th c.) established early Mewar centers (Ahar/Nagadah), developed the Chittor stronghold over centuries, and later, after Alauddin Khalji’s 1303 siege and the fall of the Guhila branch at Chittor, a Sisodia branch reconstituted Mewar power from Sisoda/Udaipur, adopting the “Rana” title; earlier Guhila rulers used “Rawal.”

Statecraft: forts, feudatories, and ceremony

Rajput kingship privileged fortified capitals (kot/garh), a mobile core army, and a web of feudatories (samantas) bound by grants, honor, and campaign duties. Titles (Maharajadhiraja, Paramabhattaraka) and ritual (yajnas, panegyrics, genealogies) underwrote legitimation, while marriage diplomacy stitched regional alliances. Land grants—often recorded on copper plates—transferred revenue rights and administrative immunities, nurturing temple economies and local elites allied to courts. As imperial centralization waned, layered sovereignty—overlords, feudatories, and autonomous chiefs—became the norm, producing fluid coalitions and recurrent border wars.

Economy, trade, and urbanism

Despite persistent warfare, Rajput polities sustained agrarian expansion, artisanal clusters, and long‑distance exchange. Gujarat’s Solanki ports and Malwa’s market towns linked the Arabian Sea to the Gangetic plain; Delhi–Ajmer–Kannauj corridors funneled caravan trade inland. Temple‑cities (Khajuraho, Osian, Kiradu, Modhera, Mt. Abu precincts) doubled as ritual‑financial hubs, with donations funding festivals, welfare, and guilds. Fortified hill‑capitals (Chittor, Ranthambore, Jalore, Jaisalmer) secured caravan taxes and regulated movement through desert and plateau passes. Monetary media varied by region and era, from bullion to fiduciary copper, with tribute and plunder periodically re‑mobilizing wealth for fort works and temples.

Culture, architecture, and memory

Rajput courts patronized Sanskrit kavya and emergent vernaculars (early Apabhramsha/old Rajasthani), bardic traditions, and monumental architecture.

Temples: Khajuraho (Chandela), Modhera and Sun‑cult precincts (Solanki), Dilwara/Abu and Osian complexes (Jain and Shaiva), and widespread nagara‑style shrines testify to sculptural and ritual investment.

Forts: Chittorgarh’s layered building phases, Ranthambore’s strategic bastions, and Jalore’s frontier watch showcase defensive ingenuity and symbolic sovereignty.

Court culture: Genealogies crafted links to epic lineages; rajadharma ideals fused martial valor (śaurya), honor (maryada), and hospitality (atithi‑satkara). Later literary cycles—romantic‑heroic legends—shaped popular memory, sometimes distancing from hard archival facts.

External pressures and frontier defense

Rajput houses sat astride invasion corridors. In the 10th–11th centuries, Ghaznavid raids probed the doab and Rajasthan; Rajput coalitions and rivalries alternately blunted and enabled incursions. Twelfth‑century pressures culminated in the Ghurid advance: Prithviraj Chauhan’s initial success was reversed at the Second Battle of Tarain (1192), opening the Delhi‑doab to Turkic military‑fiscal systems. Yet Rajput polities did not disappear; many re‑localized (Ranthambore, Jalore, Bundi, Mewar), negotiated with the Delhi Sultanate, and later engaged the Mughals—sometimes resisting, sometimes aligning—carrying forward a resilient political repertoire.

Case vignettes

Tomaras to Chauhans at Delhi: Anangpal Tomar’s Lal Kot became the nucleus for Chauhan expansion; Qila Rai Pithora expanded the fort‑city, signaling Delhi’s ascent from frontier fort to metropolitan prize.

Khajuraho’s polity‑ritual nexus: The Chandela capital combined sacred kingship with cosmological temple‑plans, broadcasting authority through architecture while mediating between rival Rajput houses.

Solanki Gujarat’s maritime window: Anhilwara‑Patan anchored a coin‑guild‑port ecosystem feeding inland courts and temple cities, illustrating how sea trade underwrote inland temple economies.

Mewar’s succession: From Guhila “Rawal” at Chittor to Sisodia “Rana” at Udaipur, Mewar’s reconstitution after 1303 shows dynastic plasticity and the endurance of a hill‑fort civilizational template.

Why the Rajput template mattered

Political grammar: Fort‑anchored sovereignty, samanta networks, and ritualized kingship created durable mid‑range states that could resist, absorb, and reconfigure external power.

Cultural synthesis: Courtly patronage birthed distinctive temple urbanism, sculptural canons, and vernacular literary ecologies that became hallmarks of western and central India.

Frontier strategy: Though inter‑Rajput rivalry often helped invaders, sustained martial traditions and fort systems delayed, redirected, and localized conquest, shaping the texture of subsequent Sultanate and Mughal polities.

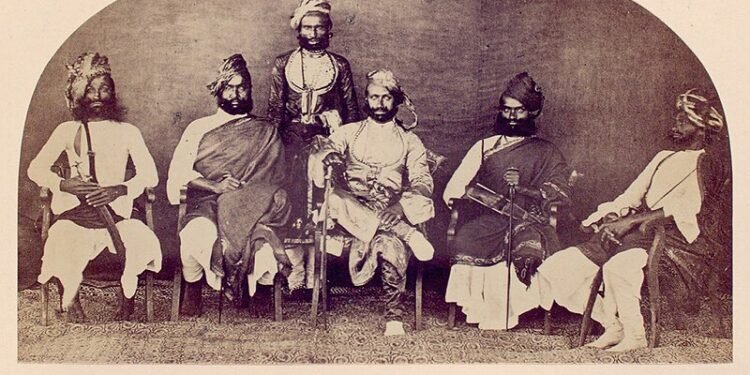

Junagarh Fort in Bikaner, Rajasthan, which was built by the Rathore Rajput rulers | Source: Wikipedia

High‑yield anchors

Capitals and cores: Tomaras (Delhi/Anandpur–Lal Kot), Chauhans (Śākambharī → Ajayameru → Delhi), Gahadavalas (Varanasi/Kannauj), Paramaras (Dhar/Ujjain), Chandelas (Khajuraho/Mahoba), Solankis (Anhilwara‑Patan), Mewar—Guhilas (Ahar/Nagadah, Chittor) → Sisodias (Udaipur).

Events: Chauhan ascendancy and Tarain (1192); Gahadavala peak under Govindachandra; Solanki temple‑maritime synergy; Paramara–Chalukya contests; Chandela cultural apex at Khajuraho.

Institutions: Samanta networks; copper‑plate land grants; temple endowments; fort taxation; marriage diplomacy; ritual titulature (Maharajadhiraja, Paramabhattaraka).

Aftermath: Post‑1192 re‑localization; Rajput branches endure at Ranthambore, Jalore, Mewar; later synthesis with Delhi Sultanate and Mughal frameworks.

Conclusion

The Rajput kingdoms converted a post‑imperial vacuum into an archipelago of fortified, temple‑centered states that stabilized frontiers, curated courtly and vernacular cultures, and experimented with layered sovereignty. Their conflicts eased external advances at critical moments, yet their infrastructural and cultural legacies outlasted conquests—reshaping cityscapes, sacred geographies, and the norms of kingship well into the Sultanate and Mughal eras. In exam terms, the Rajput age is best read as a political grammar—forts, feudatories, marriages, and ritual sovereignty—applied across terrains from Delhi to Gujarat and Mewar to Khajuraho.