Introduction

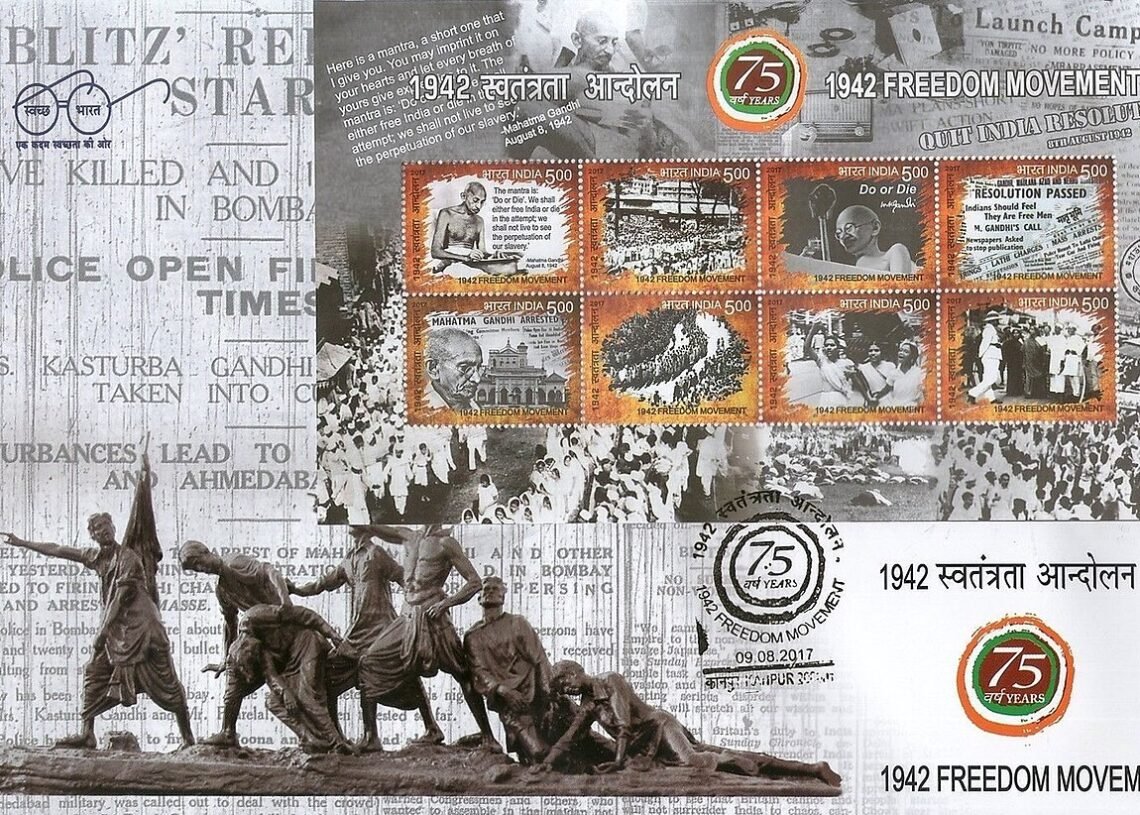

The Quit India Movement, launched in August 1942, was the last great mass upsurge against British rule and a decisive turning point in India’s freedom struggle. Called the “August Kranti” or August Revolution, it represented a clear, uncompromising demand that the British quit India immediately and marked the moment when continuing the Raj without Indian consent became practically impossible.

Background and Causes

The movement arose in the tense context of the Second World War, which Britain had entered in 1939 and into which it had involved India without consulting any Indian representatives. Wartime inflation, shortages, conscription, and repressive emergency regulations created widespread hardship and anger among peasants, workers, and the middle classes.

Politically, the failure of the Cripps Mission in early 1942 was the immediate trigger. Sir Stafford Cripps came to India with a proposal promising Dominion status and a constitution-making body after the war, but it retained British control over defence and allowed provinces to opt out of a future Indian union. The Indian National Congress rejected these terms as vague, conditional, and inadequate, seeing them as an attempt to secure Indian participation in the war without guaranteeing real freedom.

Decades of unfulfilled promises, combined with memories of Jallianwala Bagh, repeated repression of earlier movements, and the growing conviction that Britain was fighting for its own empire rather than democracy, led Gandhi and Congress to conclude that only an immediate British withdrawal could meet India’s aspirations.

The Quit India Resolution and “Do or Die”

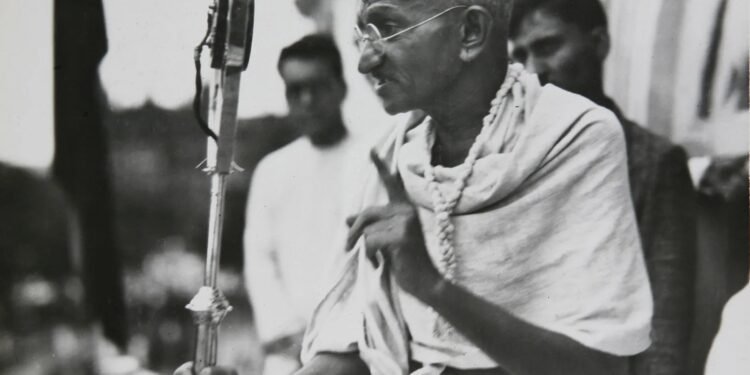

On 14 July 1942, the Congress Working Committee met at Wardha and adopted a resolution calling for a mass struggle if the British did not transfer power. This was followed by the historic All India Congress Committee session at Gowalia Tank Maidan in Bombay (now August Kranti Maidan) on 8 August 1942, where the Quit India Resolution was passed.

In his speech, Mahatma Gandhi gave the famous call of “Do or Die,” urging Indians to wage a non-violent struggle that would continue until the British left or the participants laid down their lives in the attempt. The resolution demanded:

Immediate end of British rule in India.

Formation of a provisional national government.

A commitment that free Indians would frame their own constitution through a Constituent Assembly.

Unlike earlier, more limited campaigns, the objective here was unambiguous: complete and immediate British withdrawal, not incremental reforms.

British Crackdown and Outbreak of the Movement

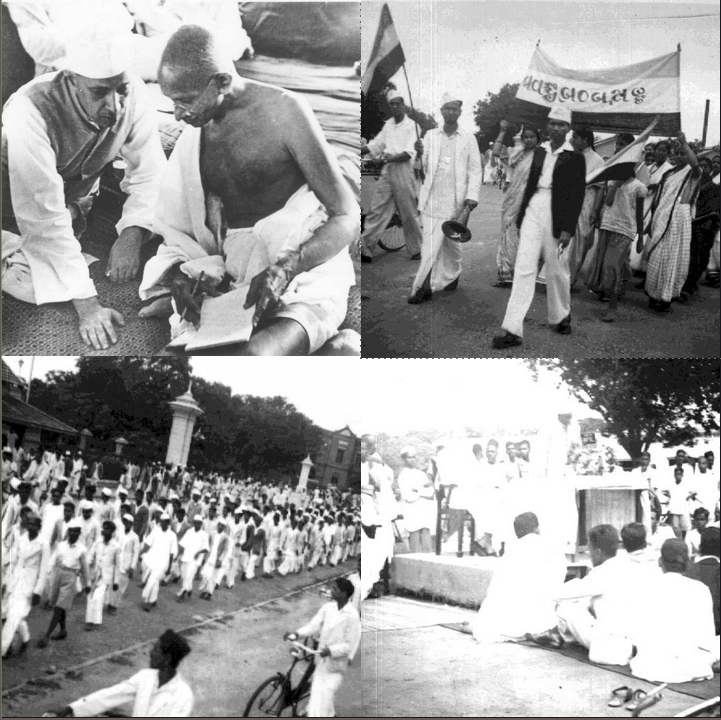

The colonial government responded within hours. In the early morning of 9 August 1942, Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Patel, Maulana Azad and virtually the entire top Congress leadership were arrested, and the Congress was declared unlawful. This decapitation strategy was intended to prevent any organized movement, but it instead triggered spontaneous protests across the country.

With central leadership behind bars, local leaders, students, workers, and peasants stepped into the vacuum. Hartals, strikes, and mass demonstrations erupted in cities and towns; crowds attacked symbols of colonial power, including police stations, post offices, courts, and government buildings. Railway tracks were uprooted, trains derailed, and telegraph lines cut in many regions, especially in Bihar, eastern Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Bengal, and Odisha.

Gandhi had called for non-violence, but in the absence of central direction and under severe repression, much of the movement took on a semi-insurrectionary character, blending civil disobedience with sabotage aimed at paralyzing the colonial administration.

Phases and Parallel Governments

Historians often describe two broad phases of the movement. The first, from August to about September 1942, was an open mass phase marked by strikes, demonstrations, and direct confrontation with state authority. The second phase saw the emergence of underground networks and quasi–guerrilla resistance, which continued for nearly two years in some regions.

A striking feature was the rise of “parallel governments” where British control had effectively collapsed.

In Ballia in eastern UP, Chittu Pandey led a short-lived national government in August 1942, taking over local administration and releasing prisoners before British forces reasserted control.

In Tamluk in Midnapore district of Bengal, the Jatiya Sarkar (National Government) was formed in December 1942 and functioned until 1944, setting up people’s courts, organizing relief work, enforcing prohibition, and even managing defence.

In Satara (Maharashtra), the “Prati Sarkar” engaged in underground activities, targeted collaborators, and oversaw parallel justice through nyayadan mandals.

These experiments, though localized, demonstrated both the erosion of colonial authority and the capacity of Indians to manage their own affairs.

British Repression

The government’s response was one of the most severe in the history of the Raj. Over 100,000 people were arrested; Congress was banned, and its funds seized. Police and military forces used firing, lathi-charges, aerial machine-gunning in some places, and collective punishments to crush resistance.

Press censorship was tightened, nationalist newspapers closed, and even possession of Congress literature or the national flag could invite prosecution. Casualties ran into hundreds—some estimates suggest more than a thousand killed and many more injured during clashes and firing incidents. Yet in many areas, lower-level officials, policemen, and railway workers sympathized with or quietly assisted the movement, reflecting a significant loss of loyalty within the colonial apparatus.

Role of Emerging Leaders and Mass Participation

With Gandhi and senior leaders in prison, younger and more radical activists came to the fore. Socialists like Jayaprakash Narayan and Ram Manohar Lohia organized underground communications, coordinated sabotage, and kept alive the call for national revolt. Aruna Asaf Ali became a symbol of resistance after hoisting the national flag at Gowalia Tank Maidan on 9 August and evading arrest for months.

The movement saw broad-based participation: students walked out of schools and colleges, workers joined strikes and sabotage, peasants attacked revenue offices and disrupted communications, and women acted as couriers, organizers, and protest leaders. Unlike some earlier movements that remained more urban and middle-class, the Quit India Movement drew heavily on the rural poor, tribal communities, and small-town youth, giving it a distinctly grassroots character.

Limitations and Criticisms

Despite its intensity, the Quit India Movement did not achieve its immediate objective of forcing British withdrawal. Several limitations are noted by scholars:

The absence of central leadership after the initial arrests meant there was little coordination or long-term strategy.

Violence in many areas allowed the government to justify harsh repression and to portray the movement as lawless.

Major organizations like the Muslim League, the Communist Party of India (after Germany attacked the USSR), and the Hindu Mahasabha did not support the movement and in some cases opposed it, limiting national unity.

Leaders such as B.R. Ambedkar and Periyar criticized the timing and methods, arguing that it did not adequately address the concerns of Dalits and non-Congress groups.

Even so, these criticisms did not erase the movement’s deeper political effects.

Impact and Historical Significance

In the long run, the Quit India Movement fundamentally altered the balance between Britain and India. It convinced British policymakers that India could only be ruled through continuous repression and that post-war reconstruction would be incompatible with maintaining an unwilling empire. As one British assessment later acknowledged, it was “by far the most serious rebellion since 1857.”

Within India, the movement:

Cemented the demand for complete independence (Purna Swaraj) as the only acceptable outcome, displacing earlier ideas of dominion status.

Deepened political consciousness across villages and small towns, widening the base of nationalism beyond educated elites.

Produced a new generation of leaders and activists who later played significant roles in independent India’s politics and social movements.

Though independence came only in 1947, many historians see 1942 as the point at which British departure became a question of timing rather than principle.

Conclusion

The Quit India Movement of 1942 was not a neatly controlled satyagraha but a vast, turbulent, and often leaderless uprising demanding an immediate end to colonial rule. It suffered from repression, lack of coordination, and political divisions, yet it succeeded in demonstrating that the British Raj no longer possessed moral authority or secure consent to govern India. In that sense, “Quit India” marked the final decisive phase of the freedom struggle, transforming the call for independence into an irresistible national demand that culminated in freedom five years later.