Introduction

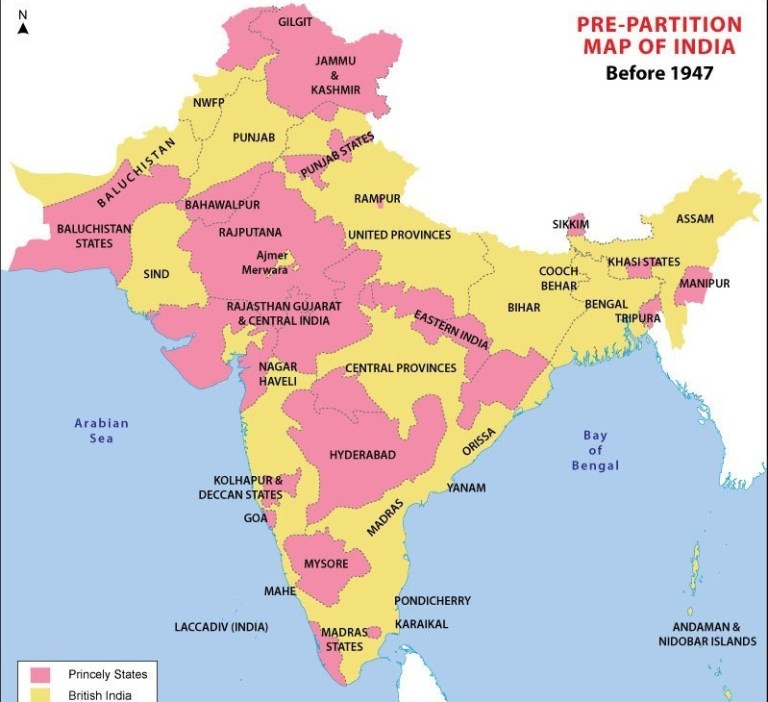

Between 1947 and the early 1950s, more than 560 princely states were brought into the Indian Union through a calibrated mix of persuasion, legal instruments, public guarantees, and limited force. Steering this process, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and V. P. Menon deployed the Standstill Agreement and the Instrument of Accession to secure defence, external affairs, and communications for India, while assuring rulers internal autonomy initially; the few holdouts—Junagadh, Hyderabad, and Jammu & Kashmir—were resolved via plebiscite, negotiation, and, when necessary, military action.

Background and choices in 1947

The Indian Independence Act 1947 ended British paramountcy, leaving princely rulers to choose among accession to India, accession to Pakistan, or claims to independence. To avoid Balkanization, the interim Government formed a States Department under Patel with Menon as secretary and crafted a practical path to accession, foregrounding popular will, strategic security, and economic viability.

Instruments and guarantees

Standstill Agreement: Maintained status quo in existing administrative arrangements to ensure continuity while negotiations proceeded.

Instrument of Accession (IoA): Rulers ceded three union subjects—defence, external affairs, and communications—under terms aligned with the Government of India Act 1935 schedules; internal autonomy was retained on other matters at this stage.

Safeguards and assurances: Clauses preserved rulers’ autonomy beyond the ceded subjects, kept them outside the not‑yet‑framed Constitution initially (Clause 7), and offered dignities such as privy purses in the transition—measures designed to make accession acceptable.

Fast‑track accessions and first hurdles

By 15 August 1947, most states had signed the IoA; a handful delayed or sought alternatives, prompting intensive outreach by Mountbatten, Patel, and Menon. Border states like Jodhpur and Jaisalmer flirted with Pakistan, but domestic sentiment, strategic arguments, and direct appeals turned them toward India in mid‑1947.

Cases that tested the Union

Junagadh (Saurashtra): Despite an 80% Hindu population and no land contiguity with Pakistan, the Nawab announced accession to Pakistan in August 1947; economic blockade, administrative collapse, and a February 1948 plebiscite produced an overwhelming vote to join India, followed by merger into Saurashtra.

Hyderabad (the Deccan): The Nizam sought independence under a Standstill Agreement; rising militia violence (Razakars) and failed talks led to “police action” (Operation Polo) in September 1948, after which Hyderabad acceded and was integrated.

Jammu & Kashmir: Tribal incursions in October 1947 led Maharaja Hari Singh to sign the IoA at Jammu (26 October 1947), enabling Indian military aid and accession; the conflict internationalized, but the legal basis of accession rested on the signed IoA during invasion.

Mergers, unions, and administrative consolidation

After initial accessions secured India’s strategic subjects, the States Ministry moved to create viable units through mergers and unions. Very small or non‑viable states were combined into neighbouring provinces (e.g., many in Orissa, Central Provinces, Bihar) effective 1 January 1948 after an all‑night conference; scores in Gujarat and the Deccan merged into Bombay; hill states were grouped as Himachal Pradesh under central administration for security reasons. The policy emphasized dismantling internal tariff barriers, stabilizing finances, and preparing all units to accept democratic constitutions, with privy purses and dignities smoothing the transition.

Strategic method: persuasion first, force last

Patel–Menon strategy combined:

Negotiated, limited cession (IoA) plus continuity (Standstill) to attract early accessions.

Mountbatten’s personal appeals highlighting practical sovereignty and realistic options.

Flexible accommodation of local autonomy initially, followed by staged mergers for governance viability.

Calibrated coercion only when negotiations failed and public order or national security was at risk (Hyderabad).

Why integration was indispensable

Security: Fragmented sovereignties in the heartland would have undermined internal and external security, as Hyderabad’s position revealed.

Economy and mobility: Free movement of people, goods, rail/air/port operations, and communications required unified control over these lifelines across erstwhile state borders.

Democracy and popular will: In many states, public mobilization pressed for responsible government; accession and later constitutional absorption answered these demands.

Outcomes by early 1950s

Territorial unity: Save for the special cases above, virtually all 560+ states joined India by mid‑August 1947; the outliers were resolved within 1947–48 (Junagadh, Kashmir, Hyderabad).

Administrative map: Through Unions (e.g., Saurashtra, Vindhya Pradesh, PEPSU) and mergers into provinces, the patchwork was rationalized, paving the way for the Constitution (1950) and subsequent linguistic reorganization (1956).

Institutional transition: Privy purses and dignities (later abolished in 1971) and interim guarantees enabled an orderly shift from princely rule to a democratic federation.

How to narrate the story in classrooms

Documents: Read the IoA and Standstill Agreement clauses (defence–external affairs–communications) alongside Mountbatten’s appeals to see how “practical independence” was argued.

Case studies: Track timelines for Jodhpur’s turn to India, Junagadh’s plebiscite, Hyderabad’s Operation Polo, and Kashmir’s 26 October IoA to contrast tools used.

State unions: Map the creation of Saurashtra, PEPSU, and Himachal to illustrate the logic from accession to viability through mergers.

Political Integration of Princely States during the Partition of India

Conclusion

India’s political integration amidst Partition was a constitutional and diplomatic tour de force: limited, attractive accessions; guarantees for continuity and dignity; and a clear, staged path to merge hundreds of sovereignties into a governable federation. Negotiation closed most doors; coercion opened the last few only when public order and security demanded it. The result—a contiguous, administratively viable Union—made democratic constitution‑making possible and set the groundwork for later linguistic state reorganization.