Introduction

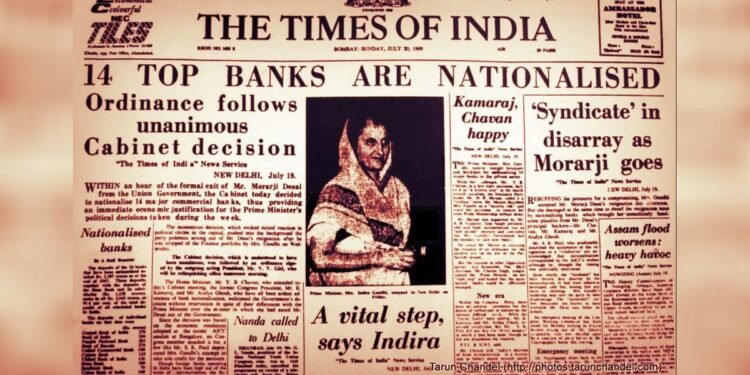

The nationalization of banks in India, executed on July 19, 1969, under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, marked a pivotal shift from private to public control over the banking sector, targeting 14 major commercial banks with deposits exceeding ₹50 crore each, which held 85% of national deposits. Enacted via the Banking Companies (Acquisition and Transfer of Undertakings) Ordinance 1969—drafted overnight and signed by acting President V.V. Giri—this move nationalized institutions like Central Bank of India, Punjab National Bank, Bank of India, Canara Bank, United Bank of India, Allahabad Bank, Bank of Baroda, Bank of Maharashtra, Dena Bank, Indian Overseas Bank, Syndicate Bank, Indian Bank, Union Bank, and United Commercial Bank (UCO), complementing the already state-controlled State Bank of India (SBI) since 1955. Ostensibly economic—to redirect credit from urban elites to rural agriculture, weaker sections, and small businesses amid 1960s crises (droughts, 1965 war, inflation, forex depletion)—it doubled as a political masterstroke against Congress Syndicate rivals, consolidating Indira’s power and rebranding her as a socialist champion.

Historical Context and Pre-Nationalization Banking

Post-independence, India’s banking remained largely private, with over 350 failures by 1969 eroding public trust and depositor savings, as funds disproportionately served big businesses and traders in urban hubs, neglecting 70% rural population reliant on moneylenders at 50-100% interest. Mid-1960s economic turmoil—1965-67 droughts slashing food output, 1965 Indo-Pak War draining reserves, balance-of-payments crisis—exposed vulnerabilities; Congress “Young Turks” like Chandrasekhar, Mohan Dharia, and K.D. Malaviya pushed left-leaning reforms for farm productivity, backward areas, and disparity reduction.

Imperial Bank (1921) evolved into SBI (1955 Act), but private banks dominated; Gadgil Study (1969) highlighted urban bias—90% credit to industry/trade vs. scant agriculture. Indira Gandhi, initially ambivalent, embraced nationalization amid Syndicate tensions post-Bangalore Congress session (July 1969), where old guard backed Neelam Sanjiva Reddy for President against her preferred V.V. Giri.

Political Maneuvering and Execution

Indira’s power struggle intensified: Syndicate controlled Congress presidentship; on July 12, they nominated Reddy. Principal Secretary P.N. Haksar preempted with an economic policy note advocating nationalization, circulated at Bangalore. Time critical—Giri’s term ended July 20, Parliament opened July 21—Indira sacked Finance Minister Morarji Desai (anti-nationalization) on July 16, assuming portfolio herself.

Midnight July 17, Haksar summoned D.N. Ghosh (Finance Ministry banking division) to draft ordinance in 24 hours; economists P.N. Dhar, K.N. Raj, I.G. Patel aided. Cabinet approved July 19; Giri signed ordinance hours before exit. At 8:30 PM, Indira broadcast nationally: banks now serve “common man,” prioritizing priority sectors. Ordinance replaced by Act August 9, 1969, after parliamentary passage despite opposition.

Legal Challenges and Second Phase

Banks challenged in Supreme Court (R.C. Cooper vs. Union of India); February 10, 1970, ruled ordinance unconstitutional—discriminatory (targeted 14 banks), inadequate compensation (book value ignored goodwill/profits). Government responded swiftly: fresh ordinance February 14, enacted as Banking Companies Act 1970, classifying banks by size/assets, raising threshold to ₹200 crore for future.

Second phase (April 1980) nationalized six more—Vijaya Bank, Oriental Bank of Commerce, Punjab & Sind Bank, Corporation Bank, Andhra Bank, New Bank of India—totaling 20 public sector banks controlling 91% deposits, 85% advances by 1990.

Objectives and Economic Rationale

Primary aims: democratize credit—allocate 40% to priority sectors (agriculture 18%, small-scale industry 10%, others); expand rural banking from 8,000 to 60,000 branches by 1990; curb private monopolies favoring 40 large houses (Tata, Birla). Social justice: uplift Scheduled Castes/Tribes, cooperatives; priority lending norms (1972) mandated targets, reducing moneylender dependence.

Post-nationalization, agricultural advances rose from ₹350 crore (1968) to ₹3,000 crore (1978); rural branches surged 15-fold, deposits 30-fold.

Impacts and Achievements

Branch network exploded: 7,219 (1969) to 57,000 (1990), 80% rural/semi-urban; deposits from ₹4,700 crore to ₹2.5 lakh crore, advances ₹3,400 crore to ₹1.5 lakh crore. Priority sector lending institutionalized (Narasimham Committee 1975); Green Revolution benefited via subsidized credit, tube wells, HYV seeds.

Public confidence restored—no failures post-1969; financial inclusion advanced, though efficiency lagged private peers initially. Politically, Indira triumphed: 1971 elections swept “Garibi Hatao,” sidelining Syndicate.

Criticisms and Challenges

State control bred inefficiencies: political interference in lending (NPA spikes), bureaucratic delays, low profitability (ROA 0.15-0.4% vs. private 1%+). Compensation disputes lingered; urban credit starved, fueling black money. Second phase diluted focus, overlapping with regional banks.

Post-1991 liberalization, Narasimham reforms (1991, 1998) reduced government stake (PSBs from 20 to 12 mergers), introduced private/foreign competition, yet PSBs hold 55% assets.

Legacy

1969 nationalization reshaped Indian finance, enabling socialist growth, but LPG era exposed rigidities; mergers (2019-20: 10 PSBs to 4 megabanks) continue consolidation. It symbolized state intervention for equity, influencing RBI’s 4% priority mandate today, balancing inclusion with viability amid fintech rise.