Introduction

Around 2600 BCE, the Early Harappan regional cultures of the northwestern subcontinent coalesced into a fully urban civilization stretching from the Indus and its tributaries to the Ghaggar‑Hakra and the Gujarat coast. This Mature Harappan phase saw large, planned cities with standardized bricks, advanced drainage, craft specialization, long‑distance trade, and an undeciphered script—an integrated cultural horizon linking Mohenjo‑daro, Harappa, Dholavira, Rakhigarhi, Kalibangan, Lothal, and more than a thousand smaller settlements.

Context and origins

Archaeologists frame Harappan history in three broad phases: Early (c. 3300–2600 BCE), Mature (c. 2600–1900 BCE), and Late (post‑1900 to c. 1300 BCE). By 2600 BCE, Early Harappan communities (Kot Diji/Amri‑Nal/Hakra traditions) transformed into large urban centers across the Indus–Ghaggar–Hakra system and Saurashtra–Kutch, driven by flood‑supported agriculture, surplus management, and increasingly standardized production. More than 1,000 Mature Harappan sites are known; key urban nodes include Mohenjo‑daro, Harappa, Ganeriwala, Dholavira, Rakhigarhi, Kalibangan, Lothal, and Rupar.

Key features and vocabulary

Standardization: Uniform baked‑brick ratios, weights and measures, seal iconography, and craft repertoires indicate an integrated cultural “oecumene.”

Urban planning: Orthogonal street grids, segregated precincts (citadel and lower town variants), wells, public tanks, and sophisticated covered drains reflect centralized planning and public hygiene priorities.

Script and seals: A short, undeciphered script appears on seals, tablets, pottery, and copper; animal motifs (unicorn, humped bull) and perforated boss seals attest administration and exchange.

Craft specialization: Bead‑making (carnelian, agate), faience, shell/ivory, metallurgy (copper‑bronze), ceramics, and textile tools (spindle whorls) point to skilled workshops and guild‑like organization.

Cities and town planning

Grids and drainage: Harappan cities pioneered large‑scale sanitation; house baths drained into covered street sewers built of baked bricks; many homes had private wells, and streets met at right angles for efficient movement.

Public structures: Granaries, warehouses, platforms, and perimeter walls functioned as food storage, flood defenses, and civic infrastructure.

Mohenjo‑daro’s Great Bath: A waterproofed, brick‑lined tank within the citadel complex—likely ritual in function—exemplifies public water architecture.

Variations across sites: Dholavira shows a three‑part plan (citadel–middle town–lower town) and monumental waterworks; Lothal has a dock‑like feature linked to maritime exchange; Rakhigarhi and Kalibangan display regional planning idioms within a shared canon.

Economy and trade

Agrarian base: Floodplain farming of wheat, barley, pulses, and likely millets/linseed supported urban surpluses; animal husbandry complemented cropping.

Weights, measures, and logistics: Cubical stone weights in binary sequences, standardized measures, sealings, and possible bullock‑cart‑friendly avenues imply regulated commerce and taxation/storage systems.

External networks: Mesopotamian texts mention Meluhha (widely identified with Harappans); Indus‑style seals and carnelian beads appear in West Asia, while Gulf shell and West Asian materials reached Indus towns—indicating robust overseas and overland circuits.

Arts, crafts, and material culture

Sculpture and figurines: Stone and bronze figures—famously the “Priest‑King” (Harappa) and the “Dancing Girl” (Mohenjo‑daro)—alongside abundant terracotta human/animal figurines show varied techniques and functions (ritual, decorative, perhaps didactic).

Seals and iconography: Motifs like the “unicorn,” composite animals, and a horned deity in yogic posture (“Pashupati” seal) reflect symbolic repertoires whose meanings remain debated.

Pottery and pigments: Wheel‑made red ware with black‑painted geometric and naturalistic designs was common; specialized kiln technologies supported uniform production.

Governance and social organization

Civic coordination: City‑wide uniformities in bricks, drains, street alignments, and artifact styles imply strong urban governance—whether a single state, federated city‑states, or corporate councils remains debated.

Segregated precincts: Raised citadels, granaries, and public works suggest administrative/religious precincts distinct from residential quarters; yet palace‑temple monumentalism of Mesopotamian type is not evident.

Social textures: House sizes vary, indicating status differences, but archaeological signals of extreme hierarchy are muted; Harappan social order may have been urbane and managerial rather than court‑centric.

Water, climate, and the urban turn

Water mastery: Wells, reservoirs, and drains supported dense populations and public hygiene; flood management likely synchronized with monsoonal rhythms.

Climatic backdrop: Research links early urbanization to managed monsoonal floods and subsequent aridification; as rainfall patterns shifted, settlement emphasis moved eastward in the Late Harappan.

Why 2600 BCE matters

Threshold of urbanism: Around 2600 BCE, disparate Early Harappan traditions fused into a remarkably standardized urban order—the subcontinent’s first large‑scale city civilization.

Template effects: Grids, drains, weights, and administrative paraphernalia established durable subcontinental habits in planning and exchange that echo in later historical periods.

Global entanglement: Mature Harappans joined the Bronze Age “interaction sphere,” exchanging goods and techniques with West Asia while innovating locally in water, brick, and civic design.

How to read the Mature Harappan today

Compare cities: Contrast Dholavira’s three‑tiered plan and hydrological feats with Mohenjo‑daro’s dense citadel–lower town and Lothal’s maritime installation to appreciate regional ingenuity within a shared system.

Follow the infrastructure: Trace wells, house drains, street sewers, and granary platforms to see governance in bricks and channels rather than in palaces or statues.

Watch the standards: Weights, brick modules, seal formats, and script length reveal an economy of rules—logistics and administration encoded in everyday objects.

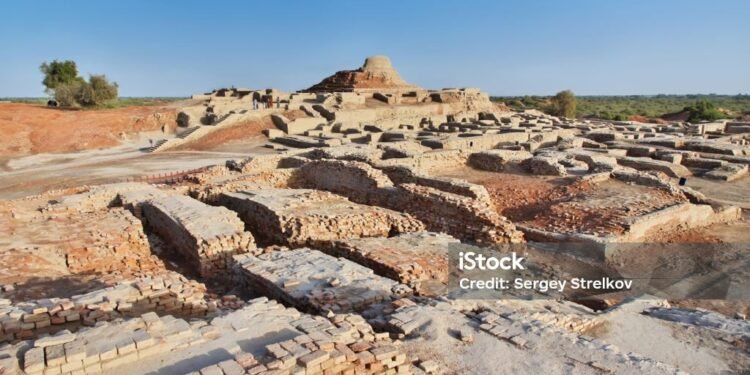

Mohenjo daro ruins close Indus river in Larkana district, Sindh, Pakistan

Conclusion

The onset of the Mature Harappan phase around 2600 BCE marks South Asia’s first great urban experiment: gridded streets, private baths and public tanks, covered sewers, standardized bricks and weights, and a web of crafts and trade linking plains, deserts, and coasts. Its cities materialized civic order and water intelligence at a continental scale, inaugurating an urban tradition whose clarity still astonishes four and a half millennia later.