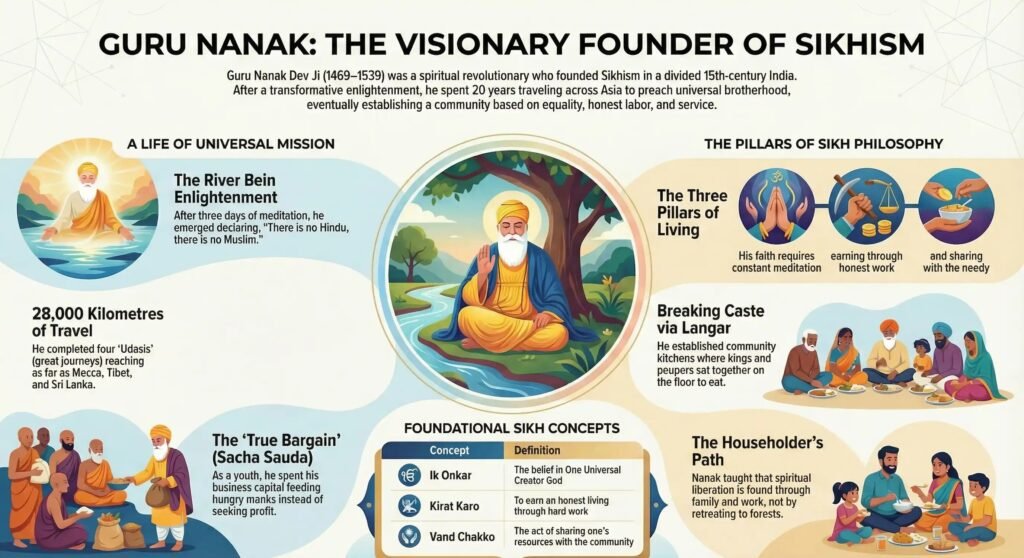

Guru Nanak Dev Ji (1469–1539) was the founder of Sikhism and the first of the ten Sikh Gurus. Born in Rai Bhoi Ki Talwandi (now Nankana Sahib, Pakistan), he showed signs of spiritual depth from a young age. He spent his early years working as a storekeeper in Sultanpur Lodhi before a transformative experience in the River Bein led him to declare, "There is no Hindu, there is no Musalman." He spent the next 20 years traveling across Asia (known as Udasis), visiting places as far as Mecca in the West, Tibet in the North, and Sri Lanka in the South. In his later years, he settled in Kartarpur, where he established the first Sikh community based on the principles of Naam Japo (Meditation), Kirat Karo (Honest Work), and Vand Chakko (Sharing). He introduced the institution of Langar (community kitchen) to break caste barriers. Before his death in 1539, he passed his spiritual light to Bhai Lehna, who became Guru Angad Dev.| Feature | Details |

| Birth Date | April 15, 1469 (Celebrated on Kartik Purnima) |

| Birth Place | Rai Bhoi Ki Talwandi (Nankana Sahib, Pakistan) |

| Parents | Mehta Kalu (Father) & Mata Tripta (Mother) |

| Sister | Bebe Nanaki |

| Wife | Mata Sulakhni |

| Children | Sri Chand & Lakhmi Das |

| Companion | Bhai Mardana (Muslim Rabab player) |

| Key Concepts | Ik Onkar, Three Pillars (Naam, Kirat, Vand) |

| City Founded | Kartarpur (Pakistan) |

| Successor | Guru Angad Dev Ji |

The Divine Child of Talwandi

Guru Nanak was born in 1469 into a Hindu Khatri family. From childhood, he was different. At the age of five, he voiced questions about the purpose of life. At age seven, he surprised his schoolteacher by explaining the deeper meaning of the first letter of the alphabet, claiming it represented the Unity of God.

A famous incident from his childhood is the Sacred Thread Ceremony (Janeu). When the priest tried to put the thread around his neck, the nine-year-old Nanak refused, asking for a thread made of “compassion, contentment, and truth” that would not break or get soiled, unlike the cotton thread.

Foundation of the Khalsa 1699: The Birth of the Saint-Soldiers

The Sacha Sauda (True Bargain)

As a young man, his father gave him 20 rupees to start a business. On his way, Nanak met a group of hungry sadhus (holy men). Instead of trading, he spent all the money feeding them. When he returned, he told his father he had made a “True Bargain” (Sacha Sauda). This act laid the spiritual foundation for the concept of Langar (Free Kitchen).

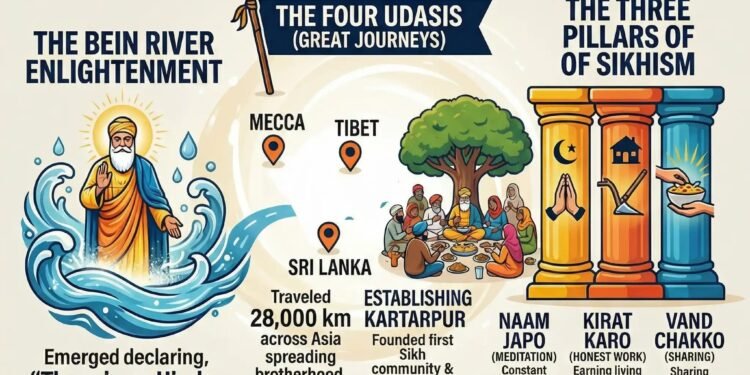

Enlightenment at River Bein

Nanak moved to Sultanpur Lodhi to live with his sister Bebe Nanaki and worked at the granary of Nawab Daulat Khan Lodi. One morning, at the age of 30, he went to the River Bein for a bath and disappeared. He remained missing for three days.

When he re-emerged, his first words were: “Na koi Hindu, na koi Musalman” (There is no Hindu, there is no Muslim; all are one in God’s eyes). This marked the beginning of his mission to preach universal brotherhood.

Martyrdom of Guru Arjan Dev: The First Sacrifice in Sikh History

The Four Udasis (Great Journeys)

Guru Nanak spent nearly 20 years traveling on foot, covering an estimated 28,000 kilometers. He was accompanied by his lifelong friend, Bhai Mardana, a Muslim minstrel who played the Rabab while Nanak sang hymns.

- First Udasi (East): He visited Haridwar, Banaras, Jagannath Puri, and Assam. In Haridwar, seeing people throwing water towards the sun for their ancestors, Nanak started throwing water in the opposite direction (West). When questioned, he reasoned that if their water could reach the sun millions of miles away, his water could certainly reach his fields in Punjab.

- Second Udasi (South): He traveled to Sri Lanka, meeting Shivnabh, the King of Jaffna.

- Third Udasi (North): He trekked through the Himalayas to Tibet and Ladakh, debating with the Siddhas (Yogis) at Sumer Parbat about the importance of living in society rather than renouncing it.

- Fourth Udasi (West): He traveled to Mecca, Medina, and Baghdad. In Mecca, when he slept with his feet towards the Kaaba, a Qazi scolded him. Nanak politely asked him to turn his feet in a direction where God did not exist. The Qazi realized that God is omnipresent.

The Settlement at Kartarpur

After his travels, Guru Nanak settled in Kartarpur (City of the Creator) on the banks of the River Ravi. Here, he put his teachings into practice. He worked as a farmer, proving that one could reach God while living a householder’s life.

He established the Langar, where people of all castes—kings and paupers—sat together in a row (Pangat) to eat. This was a revolutionary act in caste-ridden India.

Martyrdom of Guru Tegh Bahadur: The Sacrifice for Human Rights

The Three Pillars of Sikhism

Guru Nanak crystallized his philosophy into three simple principles:

- Naam Japo: Constant meditation on the name of God.

- Kirat Karo: Earning a living through honest, hard work.

- Vand Chakko: Sharing one’s earnings with the needy.

The Succession and Death

As his end neared, Guru Nanak tested his sons and disciples to find a worthy successor. Bhai Lehna, a devoted disciple, passed every test of humility and obedience. Nanak renamed him Angad (part of my own limb) and installed him as the Second Guru.

On September 22, 1539, Guru Nanak merged with the eternal light. Legend says that Hindus wanted to cremate him and Muslims wanted to bury him. But when they lifted the sheet covering his body, they found only fresh flowers. The Hindus took half and cremated them; the Muslims took the other half and buried them.

Annexation of Punjab 1849: The Fall of the Sikh Empire

Quick Comparison Table: Guru Nanak vs. Contemporary Saints

| Feature | Guru Nanak Dev Ji | Kabir Das | Chaitanya Mahaprabhu |

| Region | Punjab (North-West) | Banaras (North) | Bengal (East) |

| Focus | Monotheism (Ik Onkar) | Formless God (Nirguna) | Devotion to Krishna (Saguna) |

| Social Reform | Rejected Caste & Asceticism | Rejected Caste | Rejected Caste |

| Language | Punjabi / Vernacular | Hindi / Vernacular | Bengali / Sanskrit |

| Legacy | Founded a Distinct Religion (Sikhism) | Influence on Bhakti/Sikhism | Gaudiya Vaishnavism |

Curious Indian: Fast Facts

- The Baghdad Inscription: In Baghdad, a stone inscription was discovered that mentions “Baba Nanak Fakir,” verifying his visit to the Middle East.

- The Needle Story: A wealthy man, Duni Chand, asked Nanak to take a needle to the afterlife for him. Nanak refused, asking, “How can I take it when you can’t take your wealth?” This taught Duni Chand the futility of materialism.

- Babar Vani: Guru Nanak witnessed the invasion of the Mughal Emperor Babur in 1520. He wrote hymns (preserved in the Guru Granth Sahib) criticizing the brutality of the invasion, calling Babur’s army a “marriage party of sinners.”

- Mool Mantar: The first composition in the Guru Granth Sahib is the Mool Mantar, Guru Nanak’s definition of God: Ik Onkar (One Universal Creator God), Satnam (The Name is Truth), Karta Purakh (Creative Being Personified).

Conclusion

The Life of Guru Nanak was not just a spiritual journey but a social revolution. In a world divided by walls of religion and caste, he built bridges of humanity. He did not ask his followers to retreat to the forests but to find God in the sweat of their labor and the service of others. His legacy is the Sikh Panth—a community that, five centuries later, is still known worldwide for its service (Seva) and bravery.

Reign of Akbar 1556-1605: The Golden Age of the Mughal Empire

If you think you have remembered everything about this topic take this QUIZ

Results

#1. At the age of nine, why did Guru Nanak refuse to wear the ‘Janeu’ (sacred thread) during the traditional ceremony?

#2. What was the ‘True Bargain’ (Sacha Sauda) that Guru Nanak performed as a young man?

#3. Following his transformative experience at the River Bein, what was Guru Nanak’s first public declaration?

#4. During his first Udasi (great journey) in Haridwar, why did Guru Nanak throw water towards the West?

#5. What was the focus of Guru Nanak’s debate with the Siddhas (Yogis) at Sumer Parbat in the Himalayas?

#6. Which incident in Mecca taught the Qazi that God is omnipresent?

#7. In the context of the ‘Three Pillars of Sikhism’, what does ‘Vand Chakko’ signify?

#8. How did the institution of ‘Langar’ at Kartarpur specifically challenge the existing caste system?

When and where was Guru Nanak born?

He was born on April 15, 1469 (celebrated on Kartik Purnima) in Rai Bhoi Ki Talwandi (now Nankana Sahib, Pakistan).

What are the three pillars of Guru Nanak’s teachings?

They are Naam Japo (Meditate), Kirat Karo (Work Honestly), and Vand Chakko (Share with others).

Who was Guru Nanak’s constant companion during his travels?

Bhai Mardana, a Muslim minstrel who played the Rabab, accompanied him for 27 years.

What is the significance of “Ik Onkar”?

It is the opening phrase of the Mool Mantar, meaning “There is One God”, emphasizing the monotheistic nature of Sikhism.

Who succeeded Guru Nanak?

Guru Angad Dev Ji (formerly Bhai Lehna) succeeded him as the second Sikh Guru.