Introduction

The Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, lasting from 5 August to 23 September, stemmed from unresolved Kashmir disputes post-1947-48 war, where Pakistan controlled ~37% and India ~63% of the princely state despite UN ceasefire violations—no Pakistani withdrawal, no Indian plebiscite. Pakistan launched Operation Gibraltar (5 August) with 5,000-40,000 Azad Kashmir regulars disguised as locals infiltrating via 10 forces (Salahuddin, Ghaznavi, etc.) to incite Muslim uprising in Srinagar Valley, Rajouri, Kargil—but locals tipped off India, capturing infiltrators and foiling rebellion. India retaliated by seizing Haji Pir Pass (26-28 August, 68th Infantry Brigade under Brig. ZC Bakshi), shortening Uri-Poonch logistics 200km while threatening Pakistani supply lines; war escalated to full fronts in Punjab-Rajasthan-Sialkot amid Cold War alliances—Pakistan’s US Pattons/F-86s/SEATO/CENTO vs India’s Soviet MiG-21s/T-55s post-1962 China wake-up.

Strategic Prelude and Alliances

Post-partition, Pakistan allied West (1954 US Mutual Defense Pact, £1bn aid: M48 Pattons, F-104s, Centurions) eyeing Kashmir “now or never” amid Nehru’s 1964 death, Hazratbal relic riots, Sheikh Abdullah release; Rann of Kutch clashes (April 1965) boosted morale. India, non-aligned but post-1962 humbled, sourced Soviet MiG-21s/T-55s, French Ouragans, limited US C-119s; Kashmir integrated via Article 370 dilution, rejecting joint plebiscite.

Pakistan’s Ayub Khan miscalculated uprising; Gibraltar failure prompted Operation Grand Slam (1 September, Chhamb-Akhnoor)—12th Infantry/1st Armored Divisions advanced 7-8km with Pattons over Indian AMX-13s, but command switch (Gen. Akhtar Malik to Yahya Khan) delayed, allowing Indian 20th Lancers/IAF halt. India preempted by crossing international border (6 September), targeting Lahore to divert forces.

Major Battles: Punjab Front

India’s three-prong Lahore offensive (15th/7th Infantry, 4th Mountain Divisions, Deccan Horse/1st Armored): Northern Amritsar-Lahore axis—3 JAT reached Dograi/Batapore but ammo-short withdrew under shelling; Central Khalra-Burki—7th Division/48th Brigade captured Burki (11 September) after Pakistani 1st Armored tank counterattack repelled.

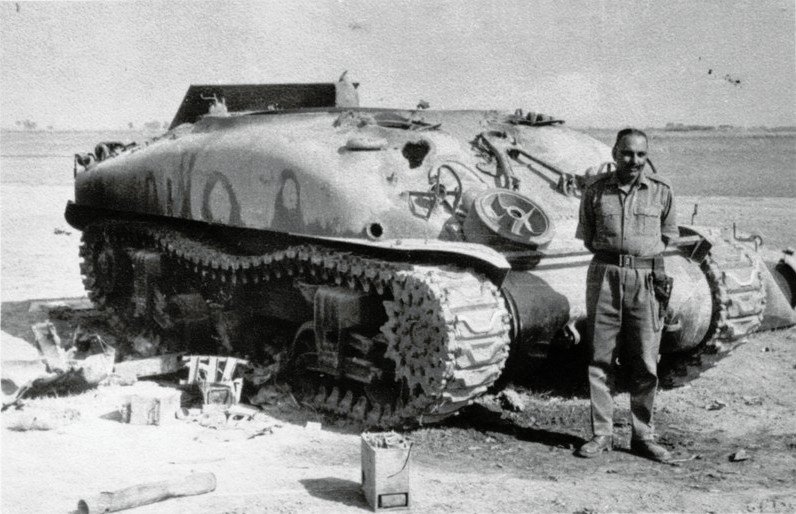

Southern Khemkaran: Pakistani 1st Armored (Pattons) captured Khemkaran (8 September); Indian 4th Mountain/2nd Armored fell back to Asal Uttar, flooding fields, mining, ambushing in cane—destroyed ~97-100 Pattons vs 10-30 Indian (Centurions/Shermans superior night-firing), earning “Patton Nagar”; CQMH Abdul Hamid (4 Grenadiers) posthumous PVC for 4+ tanks via recoilless gun. Largest tank battle since WWII halted Pakistan, crippling its armor (200+ total losses vs India’s 100).

Sialkot Sector Clashes

India targeted Sialkot junction (8 September, 1st Armored/6th Mountain/14th-26th Infantry Divisions) to sever Punjab-Kashmir logistics: Battle of Phillora (10 September)—three-way assault (1st Armored north, 17th Poona Horse/62nd Cavalry west, 43rd Lorried east) under artillery; captured vs Pakistani 6th Armored/24th Brigade, Centurions outperforming Pattons (Pakistan 66 tanks lost, India 6); Lt. Col. MB Tarapore PVC.

Chawinda (14-17 September): Even larger tank battle (400+ tanks, 160 destroyed); Pakistani 25th Cavalry Pattons blunted Indian outflanking, emerging tactical victor—stalemate as offensives exhausted (India held initiative overall). Dograi recaptured (22 September); Rajasthan skirmishes minor.

Air and Naval Dimensions

IAF (MiG-21s, Mysteres) flew 4,000+ sorties, claiming 73 PAF kills (19 confirmed) vs 35 losses; Gnat “Sabre Slayer” downed F-86s; PAF bombed Srinagar but IAF hit Lahore/Rawalpindi. Navy limited: Indian INS Vikrant threatened Karachi (abort), Pakistani sub hangars hit; no decisive role.

Casualties: India ~3,000 killed/8,000 wounded/4,000 captured; Pakistan ~3,800 killed/9,000 wounded/4,500 captured; tanks India 128-200 lost (250-500 total), Pakistan 200-450 (700 total).

Ceasefire and Tashkent Resolution

UNSC Resolution 211 (20 September), US/USSR arms embargo pressured ceasefire (23 September); status quo largely held—India gained Haji Pir temporarily (returned Tashkent), Pakistan minor gains but failed Kashmir objectives. Tashkent Declaration (10 January 1966, USSR): Lal Bahadur Shastri-Ayub agreed pre-August CFL withdrawal; Shastri died mysteriously next day (heart attack suspected poison).

India tactically superior despite tech gap; Pakistan’s strategic failure eroded Ayub credibility (1969 ousted).

Legacy and Lessons

War validated Indian resolve, birthed heroes (Hamid, Tarapore PVCs), spurred BSF formation, defense hikes; Kashmir unchanged, paving 1971. Pakistan narrative inflated victories; India learned integrated commands, border infra. At 60 years, echoes in LAC tensions, Siachen, Kargil—strategic stalemate endures.