Introduction

The Gupta Empire (c. 319–540 CE) unified much of northern India through the reigns of Chandragupta I, Samudragupta, and Chandragupta II, combining expansive warfare, strategic alliances, decentralized administration, and cultural florescence that later observers dubbed a “Golden Age.”

Political rise and expansion

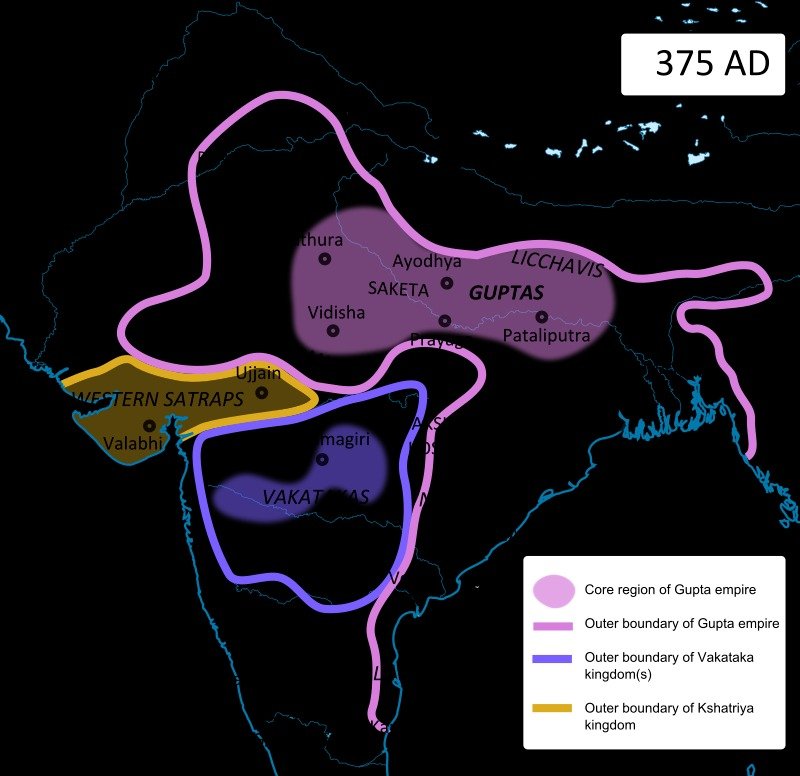

Chandragupta I inaugurated the Gupta era (c. 319–320 CE), styled Maharajadhiraja, and consolidated Magadha–Saketa–Prayaga, partly via his Lichchhavi alliance.

Samudragupta’s conquests, recorded in the Prayaga-Prashasti (Allahabad Pillar Inscription) by Harisena, detail annexations in Aryavarta, suzerainty over forest and frontier chiefs, victories in Dakshinapatha with restoration of defeated kings, and tribute from northern polities—earning him the “Napoleon of India” epithet.

Chandragupta II (Vikramaditya, Śakari) dismantled the Western Kshatrapas, annexing Malwa–Gujarat to reach the Arabian Sea, made Ujjain a secondary capital, and received the Buddhist pilgrim Faxian during his reign.

Administrative framework

Council and offices: The king worked with a mantriparishad; inscriptions attest posts like Mahābalādhikṛta (commander), Mahādandanāyaka (chief judicial/executive), Mahāpratihāra (palace), and Sandhivigrahika (war and peace/foreign affairs).

Centre–province link: Kumāramatyas and Ayuktakas bridged central and provincial levels; provinces (bhukti/desa/rashtra) under Uparikas subdivided into vishayas under Viṣayapatis or Ayuktas.

Decentralization: Land grants to Brahmanas and institutions conveyed fiscal and sometimes administrative immunities, fostering samanta hierarchies and a lighter central bureaucracy than under the Mauryas.

Society and land grants

Caste and guilds: The caste order hardened, with guilds (śreṇi) aligning to hereditary jatis; Brahmanical prestige rose alongside increasing grants (agrahāra/devadāna) that shifted local revenues and jurisdiction to donees.

Women and marginal groups: Sources like Faxian note personal freedoms alongside restrictive norms; legal texts and inscriptions reflect diminishing property rights for women and the stigmatization of certain castes in urban layouts.

Religious landscape: Vaishnavism framed royal ideology, yet rulers patronized multiple sects; Buddhist and Jain institutions persisted despite regional contractions, with councils and monasteries active beyond the core.

Economy, trade, and coinage

Maritime and inland routes: After the Shaka defeat, western seaports such as Bharuch and Sopara connected Roman–Persian trade to the Ganga heartland via Ujjain and Pataliputra.

Revenue mix: Land revenue dominated; obligations like viṣṭi (corvée) and senā-bhakta (provisions) recur in period records and later inscriptions, while urban taxes and customs underpinned market towns.

Coinage: Samudragupta and successors issued abundant gold types; Chandragupta II’s silver coinage supplanted Western Kshatrapa issues in newly annexed regions, signaling monetary integration.

Epigraphic anchors

Prayaga-Prashasti (Allahabad Pillar): Core narrative of Samudragupta’s campaigns, diplomatic suzerainties, and imperial ideology in high Sanskrit eulogy.

Mehrauli Iron Pillar inscription: Credits a Gupta monarch (often linked with Chandragupta II) with victories in the northwest; the pillar’s metallurgy symbolizes era craft prowess.

Provincial charters: Vishaya and bhukti records illuminate office hierarchies and growing immunities through grants.

Governance style vs Mauryas

Gupta rule mixed royal centrality with devolution through land grants and samanta ties, contrasted with Mauryan central departments; ministerial portfolios (e.g., sandhivigrahika) and hereditary offices show a hybrid of court governance and local autonomies.

External contacts and pilgrims

Faxian’s visit during Chandragupta II provides glimpses of roads, justice, Buddhist sites, and social practice; his narrative, alongside coin flows and port archaeology, corroborates Gupta‑era connectivity.

Stress and decline

Huna incursions post‑Kumaragupta strained frontiers and trade arteries; Skandagupta repelled major attacks but fiscal and regional pressures fragmented the imperial core, hastening post‑470s decline.

Why the Gupta template matters

Statecraft: Demonstrated durable amalgams of conquest, marriage alliances, and tributary networks stabilized by grants and provincial councils.

Social reordering: Land grants reshaped rural power and religious endowments, anchoring later temple‑centered polities across India.

Monetary‑maritime integration: Silver replacement of Shaka coinage and control of western littoral ports embedded the empire in long‑distance exchange.

Silver coin of the Gupta Emperor Kumaragupta I | Source: WIkipedia

Quick anchors

Founders: Chandragupta I; era start c. 319–320 CE.

Apex rulers: Samudragupta (Prayaga-Prashasti); Chandragupta II (Śakari, Vikramaditya; Faxian’s host).

Administrative tiers: Bhukti–Vishaya–(nagara/grama); Uparika–Viṣayapati; Kumāramatya/Ayukta linkages.

Conclusion

The Gupta Empire fused assertive expansion with negotiated suzerainty and devolved administration—broadcast by eloquent eulogies and tangible in coinage, ports, and provincial records—leaving a governance and cultural template that shaped subsequent Indian polities.