Introduction

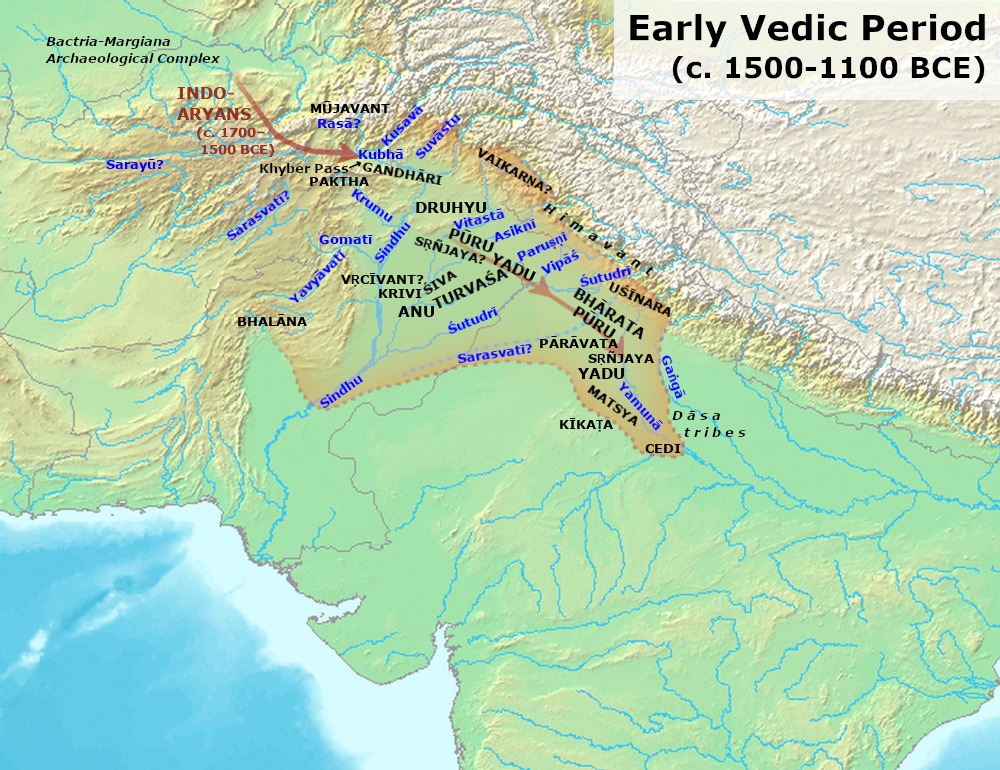

The Early Vedic Period (c. 1500–1000 BCE) describes the Rigvedic world of cattle‑keeping clans in the Sapta‑Sindhu, organized around chiefs, assemblies, and sacrificial ritual, before the shift east and agrarian intensification of the Later Vedic age.

Core geography

Rigvedic hymns situate life in the land of seven rivers—Indus and tributaries (Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas, Sutlej) plus the Sarasvati—anchoring settlements from eastern Afghanistan through Punjab into western Uttar Pradesh; later hymns enumerate rivers from Ganga westwards but the heartland remains the northwest. The Sarasvati is praised alongside Drishadvati and placed between Yamuna and Sutlej in the Nadistuti sequence, consistent with identifications in the Ghaggar‑Hakra system.

Political organization

Jana and rajan: The tribe (jana) under the rajan led war and worship, aided by the purohita (ritual specialist) and senani (war leader); the grāmāṇi administered village clusters, pointing to layered, kin‑based governance.

Councils: Sabha (smaller, often judicial) and Samiti (wider folk assembly) advised and sometimes selected the chief; Vidhata and Parishad appear as additional tribal fora, with evidence of women’s presence in some assemblies.

Warfare: Conflicts for pasture and cattle culminate in the Battle of Ten Kings (Daśarājña) on the Paruṣṇī (Ravi), where Bharata leader Sudās defeats a confederacy, paving the way toward later Kuru ascendancy.

Economy and livelihood

Pastoral core with farming: Cattle constituted primary wealth and ritual gifts; yet Rigvedic verses also mention ploughing, sowing, and wells/canals, indicating mixed agro‑pastoral subsistence in riverine plains.

Exchange: Barter dominated everyday trade; high‑value transfers invoked gold units like nishka, while bali (offerings) to the chief remained largely voluntary rather than a formal tax.

Crafts and mobility: Carpenters, chariot‑makers, weavers, metalworkers (copper/bronze) and boat usage are referenced, fitting a landscape of seasonal movement between river belts and pastures.

Society and gender

Kinship tiers: Household (kula) within vis (clan) within jana shaped identity; house‑father leadership and patriliny prevailed, with monogamy typical but elite polygyny attested.

Women’s voice: Textual memory preserves women composers (e.g., Lopamudra, Apala), and mentions their participation in councils, indicating status that later narrows with stratification.

Varna in flux: The famous Purusha Sukta, a late Rigvedic hymn, articulates four varnas; earlier layers reflect fluid roles and mobility before rigid birth‑based hierarchy set in.

Ritual and religion

Deities and aims: Hymns invoke Indra (war, rain), Agni (mediator), Varuna (ṛta/cosmic order), Soma (sacral drink/plant), Maruts (storm), Sarasvati (river/eloquence), Ushas (dawn); ritual sought rain, cattle, victory, and social prosperity.

Mode of worship: Yajña (fire‑offering) without image‑temples typifies practice; the purohita’s role in great sacrifices enhanced Brahmin prestige within clan politics.

Landscape signals from the Rigveda

Hymns list rivers in geographic order (Nadistuti), mention river crossings and floods, and repeatedly invoke Sarasvati’s might—clues scholars use to map a northwest riverine ecology and changing flows, including possible weakening of Ghaggar‑Hakra over time.

Material horizons and correlation

Archaeology correlates the later end of the Early Vedic arc with early Iron‑Age Painted Grey Ware (PGW) horizons in the upper Ganga–Yamuna basin (c. 1100–700 BCE), bridging to the Later Vedic settlement surge; debates continue on the exact overlap, but the PGW distribution matches the eastward narrative in texts. Sites like Hastinapura, Atranjikhera, and Noh anchor the PGW chronology below Northern Black Polished Ware, marking the transition toward denser agrarian polities.

Conflict patterns and consolidation

Beyond clashes with indigenous groups (often termed Dasa/Dasyu in the hymns), inter‑Aryan rivalries are prominent; the Daśarājña exemplifies competition among Bharata, Purus, Anu, Druhyu, Yadu, Turvasa and others for river corridors and pastures, with the Bharata victory later feeding into Kuru formation.

Governance ethic and justice

The rajan’s legitimacy blended prowess and piety: protecting cattle and people, distributing war‑booty through the gana, presiding over sacrifices, and heeding assemblies; sabha’s judicial role and samiti’s political mandate illustrate a consultative ethos before later monarchic consolidation.

Distinctive features at a glance

Space: Sapta‑Sindhu heartland; Sarasvati–Drishadvati prominence; Ganga‑Yamuna peripheral in early hymns.

Society: Kin‑based clans, women hymnists, flexible varna in formation.

Economy: Cattle‑wealth with farming; wells/canals; barter plus gift‑redistribution.

Polity: Rajan with sabha/samiti; militia‑style sena; riverine wars like Daśarājña.

Cult: Fire‑rituals to deified natural forces; ritual aimed at worldly welfare.

Conclusion

The Early Vedic Period captures a northwest river world of moving herds, ritual fires, and debating assemblies—clans testing strength along the Ravi and Sarasvati while composing hymns that preserved their values. Its consultative polity, mixed agro‑pastoral economy, and open social texture set the premises that later centuries would transform—eastward, iron‑aided, and stratified—into the territorial states of the Later Vedic age.