Introduction

Dhundiraj Govind “Dadasaheb” Phalke (1870–1944) is revered as the “Father of Indian Cinema” for launching India’s fully indigenous feature‑film tradition with Raja Harishchandra (1913), and for shaping the early grammar of production, camerawork, special effects, and exhibition that turned moving pictures into a national industry.

Early life and formation

Born in Trimbak near Nashik, Phalke trained widely—photography, lithography, scenic design, even stage magic—creating a toolbox that would serve his cinematic experiments. A turning point came in 1910 on viewing The Life of Christ; he grasped cinema’s power to retell Indian epics and parables for mass audiences and set out to master film craft, studying processing, optics, and trick photography before assembling a unit of his own.

Raja Harishchandra (1913): a national debut

Financing the project largely himself, Phalke wrote, produced, directed, shot, edited, and processed Raja Harishchandra, premiering 21 April 1913 (Olympia Theatre) and opening 3 May at Coronation Cinema, Bombay. Social mores barred women from acting, so Anna Salunke performed the queen’s role, while Phalke’s son Bhalchandra played the prince; the production proved an unqualified commercial success and is officially recognized as India’s first full‑length indigenous feature.

Building a studio practice

Phalke followed fast with mythologicals that honed artisanal standards into repeatable studio practice: Mohini Bhasmasur (1913), Satyavan Savitri (1914), Lanka Dahan (1917), Shri Krishna Janma (1918), and Kaliya Mardan (1919). He pioneered in‑camera effects, multiple exposures, time‑lapse, and stop‑motion gags, translating epic spectacle into screen illusions that enthralled early audiences and trained technical teams by doing.

Hindustan Cinema Film Company

To scale up, he co‑founded Hindustan Cinema Film Company (1917), launching a slate headlined by Shri Krishna Janma and Kaliya Mardan (with his daughter Mandakini as baby Krishna), even as World War‑era stock shortages and capital constraints made continuity precarious. Disagreements over costs, schedules, and creative control led him to exit and re‑enter the firm multiple times through the 1920s, emblematic of a silent‑era industry shifting from artisanal workshop to corporate studio.

Women on screen and family labor

Phalke pushed boundaries by introducing a woman performer in Mohini Bhasmasur (1913) soon after Raja Harishchandra, helping normalize women’s presence in cinema across the decade. His household doubled as a production base: Saraswatibai Phalke managed logistics, costumes, and publicity; their children acted—an under‑acknowledged foundation of Indian film’s early human capital.

A visual grammar for Indian myth and history

Phalke’s films codified:

Source material: Itihasa‑purana episodes (Ramayana, Mahabharata, Krishna lore) adapted into compact narrative reels that audiences already knew, ensuring comprehension without synchronized sound.

Technical language: Tableaux framings, intertitles with vernacular inflection, practical effects for miracles (vanishing acts, divine epiphanies), and rhythmic editing that anticipated song‑spectacle montage.

Exhibition savvy: Posters, press notices, and word‑of‑mouth campaigns cultivated repeat patrons and seeded a pan‑regional market for mythological cinema.

From artisanal mastery to industrial headwinds

The 1920s brought rapid formalization—bigger companies, distribution contracts, and diversified genres. Even as Phalke remained prolific (94 features, 27 shorts across 19 years), the arrival of sound in the 1930s and the capital intensification of production diminished space for his self‑contained model, nudging him into retirement before his legacy was widely institutionalized.

Debates and distinctions: first Indian feature

Scholars note Dadasaheb Torne’s Shree Pundalik (1912), but it relied on filmed‑theatre conventions and foreign processing; by contrast, Raja Harishchandra integrated script, shoot, processing, and local exhibition as a wholly Indian pipeline, a view the Government of India affirms in designating it the first Indian feature.

The Phalke award and remembrance

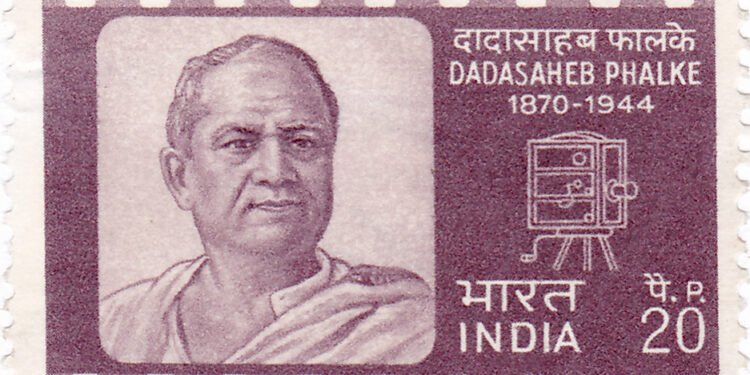

Independent India enshrined his primacy by instituting the Dadasaheb Phalke Award in 1969, the nation’s highest lifetime honor in cinema, and issuing a commemorative stamp (1971), ensuring that each generation of filmmakers is symbolically linked to the founding craftsman of their medium.

Why Phalke still matters

Indigenous production proof: He proved that Indian stories, shot with Indian crews for Indian audiences, could be financed and sustained locally—turning cinema from novelty into industry.

Technical imagination: His in‑camera tricks and practical effects were not mere spectacle; they created a visual vocabulary for portraying the divine and miraculous—an idiom that threads through Indian cinema to this day.

Cultural infrastructure: By recruiting and training performers and crew, and by cultivating audience habits around myth and morality, he gave Indian cinema its first mass‑cultural mandate in a colonized society craving shared narratives.

Timeline highlights

1870: Born at Trimbak (Nashik). Early training across visual crafts.

1910: Inspired by The Life of Christ; self‑training in camera, processing, effects.

1913: Raja Harishchandra premieres and releases to acclaim.

1913–19: Mythological hits (Mohini Bhasmasur, Satyavan Savitri, Lanka Dahan, Shri Krishna Janma, Kaliya Mardan).

1917: Co‑founds Hindustan Cinema Film Company (production scaling, recurrent disputes).

1930s: Talkies rise; Phalke exits filmmaking; 1944: passes away in Nashik.

Essential viewing and study

Films: Raja Harishchandra (narrative foundations); Lanka Dahan (spectacle and effects); Kaliya Mardan (child performance and divine play).

Archives and museums: “Phalke era” exhibits contextualize his cameras, trick‑shot notebooks, and posters as artifacts of a national origin story for cinema.

Conclusion

Dadasaheb Phalke did more than make a first film; he built a method—part artisanal ingenuity, part entrepreneurial grit—that turned Indian cinema from experiment to ecosystem. By wedding epic imagination to hands‑on technique, and by teaching crews and audiences how to “see” Indian stories on screen, he laid a foundation that a century of filmmakers has continued to raise, refurbish, and celebrate.