Introduction

The Chola thrust into Southeast Asia—culminating in Rajendra Chola I’s 1025 CE strike on the Srivijaya network—was the most audacious Indian Ocean campaign mounted by a South Asian polity before the early modern era, fusing seasonal seamanship, modular naval logistics, and targeted littoral assaults to reorder trade and diplomacy from the Coromandel to the Straits of Malacca. Far from empire-building through occupation, the expedition exemplified maritime coercion for corridor control: sail fast with the monsoon, land amphibious forces, disable rival hubs, extract submission and treasure, and depart—leaving trade lanes open under Chola deterrence.

Strategic backdrop: from Coromandel to the Straits

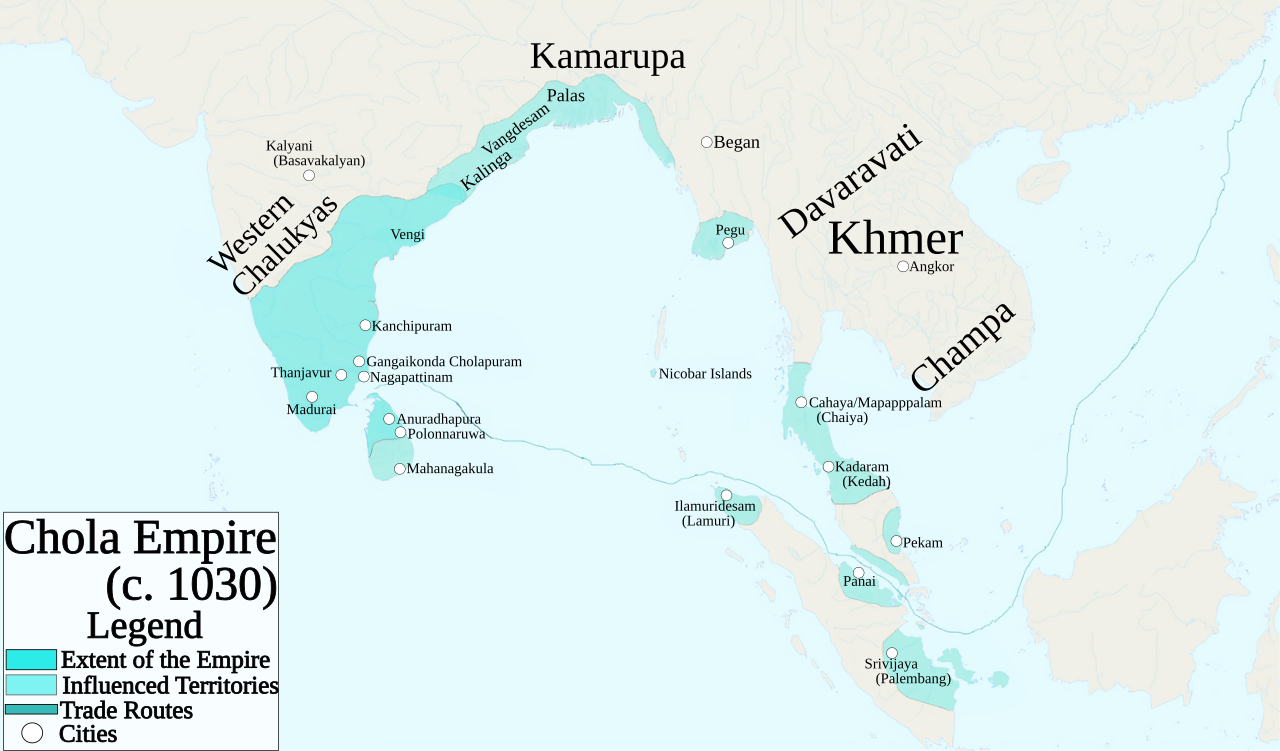

By the late 10th–early 11th centuries, the Cholas had consolidated the Kaveri delta and Coromandel ports, subdued the Pandyas, and pushed into the Chera sphere, bringing pepper routes and western ghat passes within their fiscal horizon. Control of the Sri Lankan narrows, Maldives waypoints, and Coromandel entrepôts (Nagapattinam/Kaveripattinam) positioned the realm at the hinge of Red Sea–Gulf–Bay of Bengal circuits. Across the Straits, Srivijaya’s thalassocracy yoked Sumatra–Malay Peninsula nodes, taxing passage to China; friction over tolls, plus shifting Khmer–Srivijaya rivalries and Chola prestige calculus, set the stage for a coercive demonstration eastward.

Why strike Srivijaya?

Three overlapping motives are commonly adduced:

Trade access: Neutralize Srivijaya’s interference with Chola merchant convoys and secure unimpeded passage to the Song court for high-value missions and tribute trade.

Alliance politics: Answer appeals from Srivijaya’s regional rivals (e.g., Khmer) and leverage the balance of power to Chola advantage without permanent garrisons.

Prestige and deterrence: Signal oceanic reach after Coromandel consolidation and Sri Lankan operations—projecting a message that Chola escorts and ports were under imperial protection abroad as at home.

Fleet architecture and seamanship

The Cholas did not maintain a round‑the‑year blue-water armada in the modern sense; instead, they fielded a campaign-assembled, modular navy—riverine craft, coastal transports, and escorts—synchronized with an amphibious army (infantry, cavalry, occasional elephants) for rapid littoral strikes. Hulls were planked from dense tropical timbers (jackfruit, rosewood, jamun, māva), fastened with rope joinery, then stiffened for sea, while provisioning leaned on dry staples (rice flakes, dried fish/meat) to maximize range. Navigation exploited monsoon windows, star courses, and practical cues (including releasing land‑preferring birds to gauge distance to shore), reflecting an artisanal science honed across generations of guild sailors and pilots.

Operational design: a monsoon‑timed blitz

The 1025 CE expedition likely staged from Nagapattinam, riding the fair monsoon across the Bay to the Malay Peninsula, then rolling south and east along Srivijayan ports. The pattern was consistent: strike a coastal hub, land forces, overwhelm defenses, plunder treasuries and storehouses, seize high‑value assets (including trained war elephants), and re‑embark—then repeat down the line before the strategic surprise decayed. Speed, sequencing, and weather discipline were decisive; catapults at sea mattered less than the army’s shock power ashore, delivered where Srivijaya’s nodal empire was most vulnerable—at its trade‑dependent littorals.

Logistics and amphibious tactics

Lift and landing: Transports ferried troops, mounts, and limited elephants to beachheads selected for proximity to town walls and supply depots; landings were timed with tide and wind to minimize exposure.

Intelligence and pilots: Merchant networks and expatriate guilds doubled as informants and guides, providing soundings, anchorage notes, and market intelligence across the Straits world.

Sustainment: The fleet husbanded water and staples, refreshed at captured ports, and avoided long inland pursuits; the goal was corridor paralysis, not hinterland occupation.

China, missions, and the open corridor

The payoff was corridor access: with Srivijaya shocked and its monopoly broken, Chola embassies and merchant convoys could run to Song China without hostile tolls, while Southeast Asian rulers recalibrated diplomacy toward the Coromandel. Crucially, the Cholas did not attempt to rule Srivijayan lands; their intent was to reset the rules at sea—deterring obstruction, enhancing their brokers’ leverage, and burnishing imperial repute in a crowded diplomatic arena.

Preludes and proving grounds: Sri Lanka and the Maldives

Rajaraja I’s earlier campaigns had already proven the model: occupy and tax the Sri Lankan narrows to command Palk Strait movement; subdue the Maldives (“twelve thousand islands” in later phrasing) to police mid‑ocean staging nodes; and integrate port‑temple finance so maritime profit fed domestic legitimacy and monumental endowments. These operations refined amphibious practice, convoy escort routines, and inter‑season basing—directly transferable to the Srivijaya thrust.

Ships, woodcraft, and the lost arts

Accounts emphasize the Cholas’ material mastery: selecting rot‑resistant hardwoods, joining planks with coir ropes and dowels, and sealing seams for endurance—techniques largely lost with the transition to metal hulls. Their seamanship culture balanced celestial navigation with highly local knowledge—shoals, currents, and wind shifts cataloged by pilots and passed via guilds—allowing them to make, and unmake, the Straits’ maritime geography at will.

Violence, restraint, and limited aims

The strikes were devastating where aimed—cities sacked, treasuries emptied, sacred elephants taken, Srivijaya’s aura punctured—but their limits were deliberate: no attempt to seat a Chola viceroy, no long inland lines, no occupation burden. The result was a lighter footprint with outsized systemic effect—the downstream reopening of corridors to China, the rebalancing of toll regimes, and the inscription of Chola deterrence into the calculations of Malay and mainland courts alike.

Cultural traces and memory

Southeast Asian sites preserve echoes of the encounter in temple motifs, poetic memory, and art‑historical crosscurrents, while on the Coromandel the wealth and fame cycled into massive endowments—Brihadīśvara’s stone registers enumerating gifts, rosters, and bylaws that a maritime surplus helped underwrite. The expedition thus fed both Chola soft power (as a cosmopolitan patron of temples, learning, and charitable kitchens) and hard power (as a guarantor of open seas for allied merchants).

Why the expedition mattered

Maritime doctrine: It demonstrated an Indian Ocean strategy built on modular fleets, monsoon windows, and amphibious shock—an approach that did not require permanent overseas garrisons to change behavior at sea.

Corridor sovereignty: By disciplining a toll‑taking thalassocracy, the Cholas converted prestige into pricing power for their merchants and embassies—a template for coercive trade diplomacy.

State capacity loop: Naval success funded temple‑archival governance at home, while temple‑archival governance stabilized revenue that sustained naval readiness abroad—a virtuous circle rare for the era.

High‑yield anchors

Date and target: Rajendra’s Srivijaya strike c. 1025 CE; route Nagapattinam → Malay Peninsula → Sumatran nodes, timed to monsoon.

Tactics: Fast littoral raids, rapid landings, plunder, re‑embarkation; corridor reset without occupation.

Precedents: Rajaraja’s Sri Lanka and Maldives operations; Coromandel port build‑up; China mission logic.

Ships and skills: Hardwood planking (jackfruit/rosewood/jamun/māva), rope joinery, dry rations, stellar navigation, pilotage, bird‑testing for landfall.

Outcomes: Srivijaya monopoly broken; open passage to China; strengthened Chola merchant leverage; enduring reputation as India’s premier premodern naval power.

Gangaikonda Cholapuram was built by Rajendra to celebrate his success in the Ganges Expedition | Source: Wikipedia

Conclusion

The Chola naval expedition to Southeast Asia was maritime strategy by design: use monsoon‑borne speed and amphibious punch to humble a nodal thalassocracy, reopen sea lanes, and enhance a trading state’s leverage without imperial overreach. In doing so, the Cholas fused seamanship, logistics, and statecraft into a scalable doctrine—one that harnessed the ocean’s seasonality to political ends and left a legacy of deterrence, connectivity, and cultural exchange from the Coromandel to the Straits.