Introduction

The establishment of the British East India Company (EIC) in 1600 was a defining moment not only in global commerce, but more fundamentally in the shaping of modern Indian history. Authorized by royal charter from Queen Elizabeth I, the EIC quickly evolved from a modest collective of traders seeking spices and textiles into an unprecedented transnational corporation wielding economic, military, and political power. Its foundation set in motion a series of interlinked developments that transformed India’s internal dynamics, engaged multiple global actors, and ultimately laid the administrative groundwork for two centuries of formal British colonial rule.

Early European Trade in India: Context and Rivalries

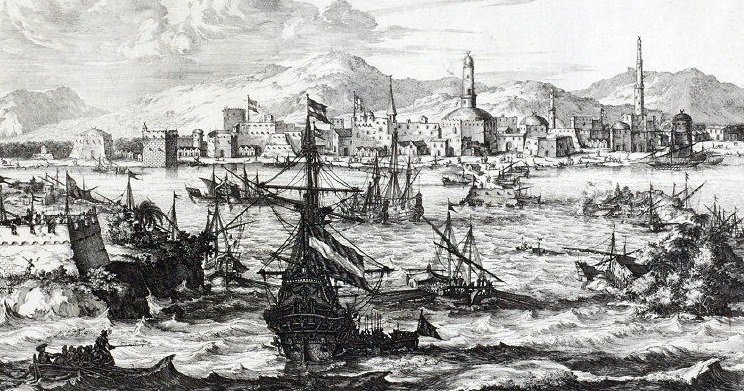

Prior to the EIC’s entry, the Indian Ocean was a bustling theatre of international commerce. The Portuguese had established early dominance after Vasco da Gama’s pioneering 1498 voyage, exploiting trade routes and setting up fortified posts on the western coast. By the mid-16th and early 17th centuries, Dutch fleets began to outcompete the Portuguese in spice trade control, establishing their own network of posts, particularly in Southeast Asia and, to a lesser extent, India.

When English traders secured their own charter in 1600, the EIC found itself vying for influence alongside not only the Portuguese and Dutch, but also the French, Danes, and later, other emergent European rivals. Each sought access to India’s lucrative exports: pepper, cotton, indigo, silk, and, especially in later centuries, tea and opium. This intense rivalry forced the EIC to innovate in diplomacy, naval power, and commercial tactics.

The Company’s Charter and Trading Monopoly

The British East India Company’s founding charter from Elizabeth I granted a monopoly to London merchants for all trade east of the Cape of Good Hope. This not only excluded other English traders, but also established a precedent for Company-led negotiation, settlement, and military action in pursuit of profits.

The early years were marked by bold voyages under men like Sir James Lancaster and Sir Thomas Roe, who negotiated with the Mughal court to establish trading privileges. The Company’s agents initially faced challenges from Portuguese sea power and existing local commercial elites, but soon secured footholds in Surat (1608), Madras (1639), Bombay (1661, through marriage alliance with Portugal’s royal family), and Calcutta (1690s).

Institutional and Economic Transformation

Growth of Trading Factories

Throughout the 17th century, the EIC gained critical commercial rights called “farmans” (royal orders) from Mughal emperors—first from Jahangir (early 1600s, for Surat) and later significant privileges from Aurangzeb. These rights allowed the Company to establish “factories”: not just warehouses, but staffed headquarters facilitating the procurement, storage, and trans-shipment of Indian goods for English markets.

The increasing number of factories and the professionalization of Company administration fostered a new class of British and Anglo-Indian intermediaries, who gained social prominence and accumulated private wealth (often through “private trade” in contravention of Company policy).

Militarization and Fortification

Facing European and Indian enemies alike, the EIC invested heavily in fortifying major settlements: Fort St. George, Fort William, and the transformation of Bombay into a fortified harbor. These strongholds became miniature city-states, offering security for British merchants but also sowing local resentment and triggering episodes of armed conflict.

From Commerce to Political Power

Expansion of Political Influence

By the early 18th century, the weakening of Mughal central authority after Aurangzeb’s death (1707) fueled regional fragmentation and offered new openings for ambitious Company officials. The EIC’s growing economic demands clashed with those of Bengal’s powerful nawabs and other local rulers, resulting in escalating disputes over trade privileges, taxation, and the Company’s expanding fortifications.

Battle of Plassey and Buxar

The tipping point arrived in the mid-1700s. Resentment over Company practices led Bengal’s Nawab Siraj ud-Daulah to move against the English in Calcutta, culminating in the seizure of Fort William. The EIC, led by Robert Clive, responded by winning the Battle of Plassey (1757) through both military action and alliances with local elites. The victory made the Company the de facto ruler of Bengal, enabling it to install “puppet” nawabs and directly influence regional administration.

Just a few years later, the Company’s victory at the Battle of Buxar (1764) decisively extinguished any remaining opposition from the Mughal emperor Shah Alam II and the rulers of Awadh and Bengal. This victory granted the EIC “Diwani”—direct revenue collection rights—for Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa.

Transition to Territorial Sovereignty

The turn from mere trading entity to territorial power was marked most clearly by the establishment of the “dual government” system in Bengal, where the Company controlled revenue and military affairs, while nominal native rulers retained a ceremonial role. Company servants amassed fortunes—often through dubious means—while Indian society and governance began to realign in response to new economic incentives and pressures.

Regulation and Reform

Growing commercial and administrative power brought problems of corruption, mismanagement, and scandal, motivating calls for oversight from Britain. The Regulating Act of 1773 introduced for the first time a Governor-General (Warren Hastings), a Supreme Court at Calcutta, and embryonic forms of British Parliamentary control.

This phase marked the gradual emergence of Company rule as a precursor to direct “Crown” rule: militarized, bureaucratic, and exploitative, but also laying the groundwork for later legal and social reforms, district administration, and many enduring features of colonial India.

Conclusion

The foundation and rise of the British East India Company transformed India’s relationship with Europe, shifting the continent’s center of gravity from a world of indigenous dynasties and Asian trading empires to one shaped by maritime capitalism, gunpowder diplomacy, and imperial ambitions. While the EIC began as a profit-seeking chartered company, its evolution into a territorial and administrative power irreversibly altered India’s political, social, and economic landscape.

By the early nineteenth century, the Company’s expansion had created new bureaucratic states, novel social hierarchies, and deeply intertwined economic systems that would persist under the British Raj. The Company’s legacy endures in debates about globalization, the ethics of commerce, and the meaning of colonial modernity—marking its foundation not just as an event in Indian history, but as a pivot for the connected histories of Britain, Europe, and the wider world.