Introduction

The Battle of Talikota (23 January 1565) stands as a pivotal turning point in the history of the Indian subcontinent, signifying both the swift and brutal downfall of the once-mighty Vijayanagara Empire and the transformation of the Deccan’s politico-cultural landscape. Fought between an alliance of four Deccan Sultanates (Bijapur, Golconda, Ahmadnagar, Bidar) and the Hindu Vijayanagara Empire, the battle’s outcome shaped the trajectory of South India and set the stage for centuries of regional reconfiguration, contestations, and new forms of cultural florescence. Its details, consequences, and enduring legacies remain intensely relevant to any understanding of India’s medieval and early modern history.

Chronological and Contextual Build-Up

Founded in 1336 as a bulwark against northern incursions, Vijayanagara blossomed into South India’s greatest imperial state under rulers like Krishnadevaraya, known for their support of art, temple architecture, and trade. However, by the 16th century, dynastic disputes, prolonged wars, and changing regional powers stressed its foundations. When Krishnadevaraya died, his son-in-law, Rama Raya, wielded de facto authority as regent to a nominal heir and soon emerged as the real power behind the throne. Rama Raya’s strategy, while initially brilliant, was predicated on internecine diplomacy: pitting Deccan Sultanate against Sultanate through shifting alliances and direct intervention in their conflicts.

This period was marked by a complex mosaic of rivalry and cooperation among the northern Sultans. However, Rama Raya’s aggressive mediation, humiliation of rivals, and opportunistic annexations fostered deep resentment. The years surrounding the final battle saw a slow but decisive alignment of interests among Sultanate rulers, aided by inter-dynastic marriages and shared economic ambitions. Their unity was fueled less by religious motives than by political pragmatism and a collective threat perception posed by Vijayanagara’s overreach.

Detailed Analysis

Political and Military Dimensions

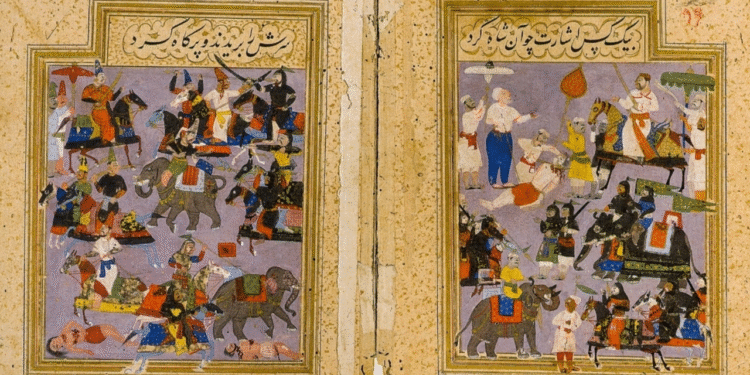

The battle site, near the villages of Rakkasagi and Tangadagi on the Krishna’s northern banks, became the arena for one of India’s largest pre-modern confrontations. The Vijayanagara Empire fielded what contemporary observers estimated as up to 140,000 infantry, over 10,000 cavalry, and more than 100 war elephants—numbers perhaps inflated but indicative of the empire’s resources. In contrast, the Sultanates’ combined armies, though numerically smaller (approx. 80,000 infantry and 30,000 cavalry), boasted advanced artillery, horse archers, disciplined cavalry, and hardened professional soldiers.

The critical phase began with the alliance’s masterstroke: feigning a search for a river crossing, lulling Vijayanagara’s vanguard into abandoning strategic ford defenses, and then rapidly doubling back for a surprise nocturnal crossing. The stage was set for a classic pincer.

Combat commenced with heavy cannon fire, though the Sultanates’ field artillery was more modern and strategically deployed than the unwieldy Vijayanagara pieces. Early gains by the Vijayanagara right and left wings were soon reversed by a combination of factors: the artillery’s deadly grapeshot (including infamous copper coin-shot), skilled archery, and above all the sudden defection and betrayal of two Muslim commanders in Rama Raya’s ranks (the Gilani brothers), leading to mass panic and a catastrophic breach. Rama Raya himself, leading from the front in accordance with old warrior traditions, was captured and executed—a fate instantly demoralizing his massive, now-leaderless host.

Socio-Economic and Cultural Impacts

The immediate aftermath was among the most traumatic in Indian urban history: the victorious Sultanate armies advanced almost unopposed to Hampi, Vijayanagara’s capital, and subjected it to months of systematic plunder, slaughter, and destruction. What had been one of the world’s richest, most vibrant cities—a center of temple-building, Sanskrit and Telugu scholarship, international commerce, and regional artistic styles—was left a smoldering ruin, never to be fully reclaimed.

This devastation fragmented both empire and economy. Trade routes decayed, port control shrank, artisans and scholars dispersed, and the flow of temple and palace patronage came to a standstill. The cultural gravity of South India shifted, and regional powers like Mysore, Madurai, Keladi, and the Nayakas of Vellore rose in the vacuum, each vying for local supremacy, but none could replicate Vijayanagara’s cosmopolitan unity.

Broader Political Consequences

The loss at Talikota also led to enduring decentralization and militarization in southern polity. No single power would unite the South for centuries, and the sultanate coalition itself soon fractured, with rivalries and Mughal incursions destabilizing the Deccan further. For the north, the defeat signaled to the Mughals the opportunity to intervene—not just militarily, but economically and culturally—ushering in a phase of new suzerainties and shifting alliances.

Religious, Architectural, and Social Legacy

While the Sultanate coalition’s motives were primarily political, the destruction that followed was colored by religious overtones—hundreds of temples and shrines were desecrated or razed, and communities uprooted. The legacy of Talikota thus became intertwined in southern memory with themes of resistance, trauma, and revival—fueling later Bhakti movements, regional identity-based assertions, and new temple-building in emerging Nayaka centers.

Outcomes, Consequence, and Significance

Collapse of Centralized Hindu Polity: Vijayanagara’s fall ended centuries of large-scale imperial Hindu rule in the South, ceding ground to smaller polities and opening the region to northern influences and European encroachments.

Socio-cultural Realignment: Urban life in Hampi was utterly destroyed, leading to the dispersion of artists, poets, and traders, and a transformation in South Indian architecture and literature.

Power Shifts: Mysore, Madurai, Keladi, Gingee, and Ikkeri Nayakas rose, while Deccan Sultanate unity was short-lived—prefiguring later Maratha and Mughal contestations for the region.

Long-term British and European stakes: The weakening and fragmentation post-Talikota indirectly smoothed the path for European influence—first Portuguese, then British—in South India’s political economy.

High-Yield Anchors

Battle of Talikota was fought on 23 January 1565 between Vijayanagara and a coalition of four Deccan Sultanates.

Immediate cause: strategic betrayal within Vijayanagara ranks, advanced artillery tactics by Sultanate armies, and capture of Rama Raya.

Aftermath: sacking and total destruction of Hampi, end of centralized southern Hindu power.

Fragmentation into successor regional polities like Mysore, Madurai, and the rise of autonomous Nayaka houses.

Cultural loss: temples, palaces, art schools uprooted or destroyed; south Indian architecture moved to Nayaka courts.

Long-term: beginnings of Deccan’s instability, later subject to Maratha and Mughal invasions, and a magnet for European commercial intervention.

The battle stands as a cautionary episode against internal disunity and mismanagement, echoing across later Indian history.

Conclusion

The Battle of Talikota endures as one of the most formative and catastrophic chapters in Indian history—a tale of hubris, shifting alliances, battlefield innovation, and tragic destruction. It irrevocably reshaped South Indian power structures, economic networks, and cultural production, seeding the ground for both new regional identities and colonial interventions. For students, scholars, and the wider public, Talikota’s lessons about unity, resilience, and the dangers of political short-sightedness remain ever relevant.