Introduction

Ashoka Maurya (r. c. 268–232 BCE) transformed from a conqueror who won Kalinga with devastating loss of life to a ruler who proclaimed remorse, renounced aggressive war, and governed through a public ethic of dhamma engraved across his empire’s rocks and pillars. His inscriptions document a program of welfare, religious tolerance, and moral suasion unique in ancient imperial history, even as he retained the capacity to defend and discipline the realm.

Before Kalinga: power and consolidation

Ascending after Bindusara, Ashoka secured the throne and continued Mauryan expansion and integration, administering key nodes like Ujjain and Taxila prior to accession. Early reign policy followed conventional rajadharma—taxation, road-building, and frontier order—within a large multiethnic state forged by Chandragupta and maintained by Bindusara. These decades set the administrative stage for the dramatic moral pivot that followed the Kalinga campaign.

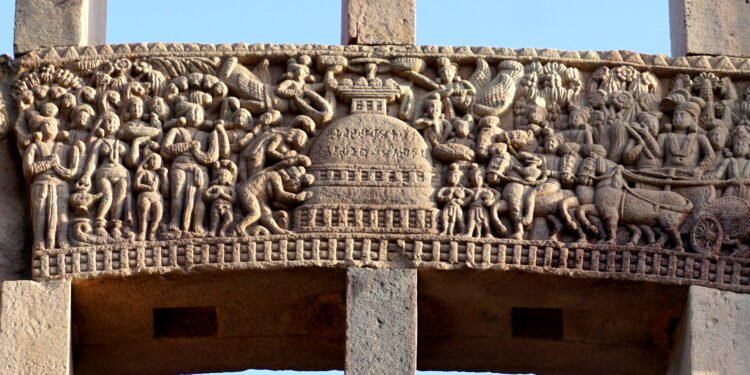

Kalinga and the pivot to dhamma

The conquest of Kalinga (c. 262–261 BCE) was the crucible: Major Rock Edict XIII records that one hundred and fifty thousand were deported, one hundred thousand slain, and “many times that number perished,” a scale that led Ashoka to public remorse and to valorize “the sound of dhamma” over “the sound of the war‑drum.” From this point his “victory by dhamma” replaced digvijaya, with efforts to spread ethical conduct at home and among neighbors—even addressing Hellenistic kings by name in the same edict.

What the edicts say

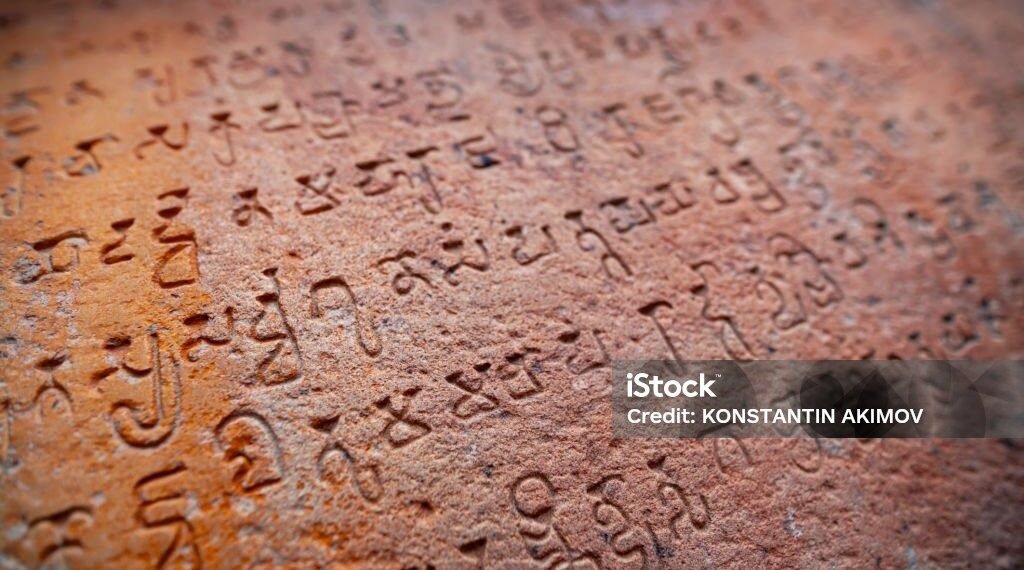

Scope and form: More than 30 inscriptions—Major and Minor Rock Edicts and seven Pillar Edicts—were incised in Prakrit (Brahmi/Kharoshthi) and, at Kandahar, in Greek and Aramaic, broadcasting policy to different regions and audiences.

Remorse and restraint: Major Rock Edict XIII articulates Kalinga remorse and the substitution of moral conquest; other edicts curb animal slaughter, condemn cruelty, and prefer persuasion over punishment while affirming the king’s duty to uphold order.

Tolerance and pluralism: Major Rock Edict XII exhorts respect for all sects; Ashoka warns that praising one’s own faith while disparaging others harms religion itself—a rare ancient assertion of principled pluralism.

Welfare measures: Major Rock Edict II details medical care for humans and animals, planting of medicinal herbs, wells, and trees; Pillar Edicts define dhamma as compassion, truthfulness, purity, and minimal sin, and charge officials (Rajukas, Dhamma‑mahamatras) with peoples’ welfare.

Administrative voice: Major Rock Edict VI shows the king’s desire for continual access to petitions—“I consider it best to meet with people personally”—blending royal vigilance with moral counsel.

Dhamma as public ethic

Ashoka’s dhamma was an ecumenical civic code: obedience to parents and teachers, kindness to servants, generosity to the poor, non‑violence towards beings, and restraint in ceremonies and fame‑seeking. He institutionalized this through Dhamma‑mahamatras, five‑year inspection circuits by Yuktas/Pradeshikas/Rajukas, and public recitation of edicts for the non‑literate, turning ethics into administrative routine.

Buddhism and councils

Inscriptional and textual traditions converge on Ashoka’s patronage of Buddhism: Minor Rock Edict 3 recommends texts for monks and laity, while Sri Lankan chronicles credit him with purifying the sangha under Moggaliputta Tissa and convening the Third Buddhist Council at Pataliputra, which organized missions to regions including Sri Lanka and the Hellenistic world. While historians debate details for lack of direct epigraphic corroboration of the council, the edicts’ concern for unity and discipline in the sangha supports a role in monastic governance.

Foreign horizons: from Kalinga to the Mediterranean

Major Rock Edict XIII names five contemporary Greek rulers—Antiochus (Amtiyoko), Ptolemy (Turamaye), Antigonus (Amtikini), Magas (Maka), and Alexander (Alikasudaro)—implying diplomatic awareness and a universalist aspiration for dhamma‑victory abroad. The Greek‑Aramaic Kandahar inscription further shows Ashoka broadcasting ethical policy beyond Indic scripts, extending his moral diplomacy into the trans‑Hellenic sphere.

Law, force, and the “forest people”

Though decrying violence, Ashoka did not abolish coercive sovereignty: edicts preserve the right to punish rebels and admonish “forest‑dwellers” to desist from wrongdoing or face royal sanction, illustrating a paternal, stern edge within a welfare‑oriented kingship. His program reduced slaughter (e.g., kitchen bans, animal protection lists) and emphasized mercy (occasional prisoner releases) but did not evacuate state authority.

Infrastructure and everyday welfare

Edicts describe planting shade trees and mango groves along roads, digging wells and watering places, establishing medical facilities for humans and animals, and appointing officers for women’s welfare—measures that tether dhamma to tangible improvements in daily life. This everyday moral economy—rest houses, roads, clinics—made compassion infrastructural.

Reading the legacy

A new public language: By carving ethical policy into stone in vernaculars, Ashoka made royal conscience a permanent, traveling pedagogy; his voice addresses officials and subjects directly, an unparalleled ancient archive of governance ideals.

Empire and restraint: He replaced expansionist glory with welfare prestige while safeguarding borders—an experiment in soft‑power sovereignty centuries before the term existed.

World religion’s hinge: Mission patronage linked Buddhism to Sri Lanka and beyond; though Buddhism later waned in much of India, these early missions helped make it a transcontinental tradition.

Key edict pointers for study

Major Rock Edict XIII: Kalinga remorse; dhamma‑victory; Hellenistic kings named.

Major Rock Edict XII: Inter‑sect tolerance; restraint in praising one’s own faith.

Major Rock Edict II: Medical care, wells, herbs for humans and animals.

Major Rock Edict VI: King’s constant accessibility; personal meetings for welfare.

Pillar Edict II & VII: Definition of dhamma; tolerance; duties of Dhamma‑mahamatras.

Kandahar inscription: Greek/Aramaic versioning of Ashoka’s ethical broadcast.

Conclusion

Ashoka’s greatness lies not only in remorse after Kalinga but in converting that remorse into a public architecture of welfare, pluralism, and ethical administration—etched into stone, spoken in multiple scripts, and carried across roads shaded by newly planted trees. He did not abandon kingship; he reimagined it as a moral office, aiming to secure “conquest by dhamma” at home and abroad while keeping the sword sheathed unless justice required otherwise. In the long arc of political thought, his edicts stand as one of antiquity’s clearest manifestos for compassionate statecraft.