Akbar (r. 1556–1605) transformed a war-torn polity into a remarkably cohesive, culturally efflorescent empire by coupling military consolidation with policies of inclusion, pragmatic administration, and a visionary ethic of sulh‑i‑kul (peace with all). His reign institutionalized interfaith dialogue, incorporated Rajput elites into imperial governance, rationalized land revenue, expanded trade, and patronized translation and the arts—laying the foundations of a distinctively syncretic Mughal statecraft and culture.

Context and origins

Ascending the throne at 13 after Humayun’s death, Akbar—guided initially by Bairam Khan—secured the Mughal position with the Second Battle of Panipat (1556) and then moved beyond survival to system-building. In a multi-ethnic, multi-faith subcontinent, his approach was to convert conquest into consensus: broaden the nobility, de‑confessionalize kingship, and construct legitimacy through fair rule and shared prosperity rather than sectarian supremacy.

Key features and vocabulary

Sulh‑i‑kul: A governing ethic of universal peace and non‑discrimination across sects/faiths; talent, loyalty, and service—not birth or creed—determined imperial preferment.

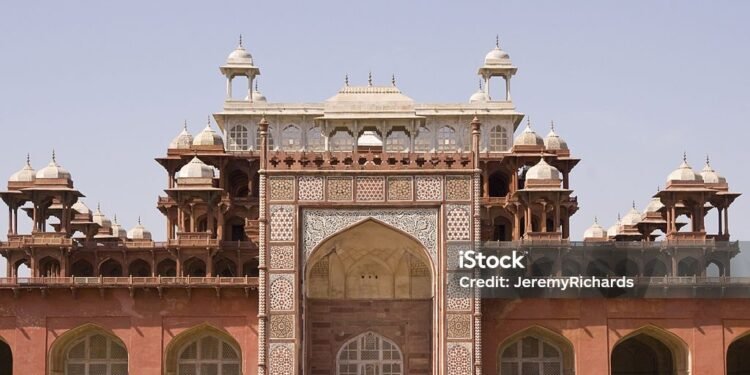

Ibadat Khana: The “House of Worship” at Fatehpur Sikri where Akbar convened interfaith debates (1575 onward), evolving into a “parliament of religions” with Sunni/Shia scholars, Brahmins, Jains, Christians, and others.

Din‑i‑Ilahi: A small ethical fellowship (1582) emphasizing devotion, reason, and moral ecumenism; never imposed, and limited in following, but emblematic of Akbar’s syncretic aspiration.

Political consolidation: from force to federation

Akbar transformed campaigns into durable compacts by privileging reconciliation over punitive rule. The Rajput policy exemplified this: matrimonial alliances (e.g., with Amer/Jaipur’s Kachhwahas), autonomous retention of internal domains, and high imperial offices to trusted Rajput nobles (e.g., Bhagwan Das, Man Singh). This policy stabilized the north-west and Rajasthan, enabling strategic expansions toward Gujarat and Bengal for maritime and commercial leverage and then into Kabul–Multan–Lahore to secure overland trade corridors.

The Roopkund Skeleton Lake Mystery: Why Were Greeks Dying in the Indian Himalayas?

Administrative innovations

Mansabdari–jagirdari: A calibrated rank-and-reward system expanded to embrace Turani, Irani, Afghan, Rajput, Deccani, and other elites, binding talent to the center and promoting meritocratic mobility within a diverse nobility.

Revenue reforms (Todar Mal): Land measurement (zabti) and the dahsala (ten‑year average) system fixed cash rates by crop and productivity, standardizing assessment and offering remissions in distress years; categorization of lands (polaj, parauti, chachar, banjar) rationalized agrarian management.

Trade and transit: Low customs, policing of highways (rahdari/thanahs), new forts and improved routes (e.g., Attock on the Indus, Khyber Pass approaches), and protection/restitution norms boosted internal and foreign commerce.

Economic and cultural economy

A stable fiscal base (agriculture, textiles, indigo, sugar) underwrote vibrant markets and courtly patronage. Akbar’s court fostered a thriving translation bureau: Sanskrit classics (Mahabharata as Razmnama, Ramayana, Puranas), as well as regional works, were rendered into Persian, expanding a shared literary sphere and facilitating cultural osmosis. Coinage reforms and aesthetic innovations (calligraphy, floral motifs, Ilahi issues) signaled ideological messaging and imperial confidence.

Religious policy and interfaith praxis

Akbar abolished the pilgrimage tax (1563) and jizya (1564), ended forced conversion of prisoners of war, supported places of worship across communities through madad‑i‑ma’ash (endowments), and even observed dietary bans during Jain and other festivals to respect plural practices. Sulh‑i‑kul, theorized by Abul Fazl, framed sovereignty above sect: a king’s duty was justice to all subjects, freedom of conscience, and discouragement of zealotry that fractured the social body.

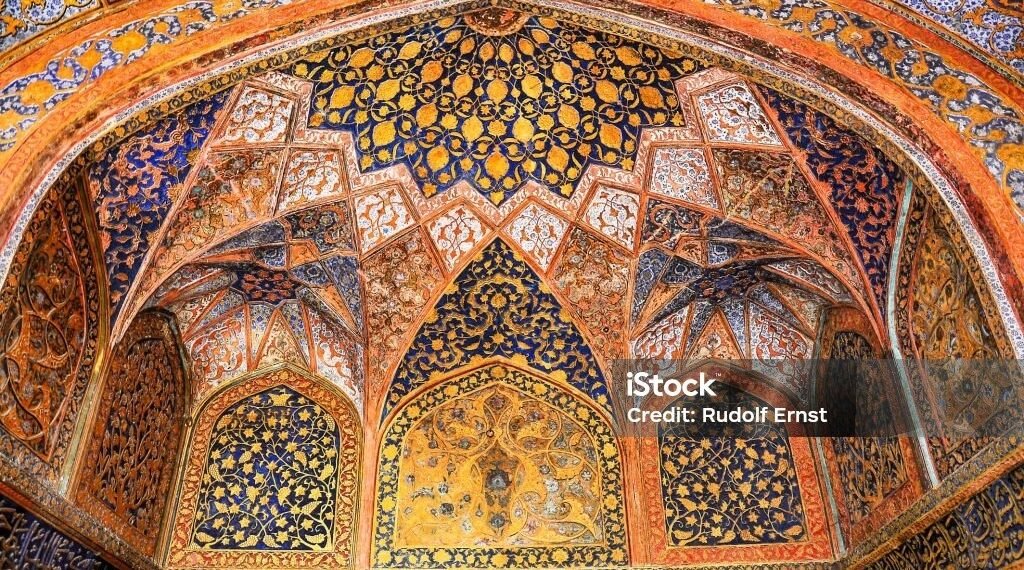

Cities and symbol-world

The new capital complex at Fatehpur Sikri embodied Akbar’s synthesis—Jama Masjid and Ibadat Khana beside non‑Islamic architectural vocabularies; audience halls (Diwan‑i‑Am, Diwan‑i‑Khas) materialized a ceremonial yet dialogic kingship. The Buland Darwaza proclaimed victory yet opened into a city of debates, translations, and arts, making space itself a pedagogical instrument of empire.

Tensions and limits

Revenue rigor sometimes pinched peasantry when court price indices exceeded countryside realities, prompting periodic recalibrations and remissions. Din‑i‑Ilahi remained symbolic rather than structural, lacking mass adoption and often misunderstood as a “new religion” rather than a courtly ethical circle. Yet the broader architecture—abolitions, interfaith debate, inclusive nobility, and legal‑administrative rationalization—outlived Akbar and shaped Mughal governance for decades.

Legacy and evaluation

Akbar’s originality lay less in isolated acts than in an integrated system: a federating Rajput policy, a capacious mansabdari, portable commercial security, and a public ethic of sulh‑i‑kul. He stabilized frontiers, expanded markets, and curated a civilizational conversation across languages and faiths, making the Mughal court a clearinghouse of Indian and transregional knowledge. Even criticisms—of central demands or court cosmology—confirm the scale and ambition of an experiment that reframed kingship from sectarian to civic, and culture from inheritance to dialogue.

How to read Akbar today

Governance: As a model of pragmatic inclusion—recruit the best across identities; align rank with service; codify fairness; and make dissent part of deliberation rather than sedition.

Culture: As translation and encounter—reduce distance between knowledge systems, invest in public institutions (debating houses, archives), and use aesthetics to signal civic values.

Economy: As market‑state synergy—secure routes, lower frictions, standardize assessments with elasticity in distress, and protect commercial actors with enforceable norms.

Conclusion

Akbar’s greatness rests on a statesman’s instinct and a humanist’s horizon: fold difference into order without crushing it, let revenue serve culture and culture leaven rule, and advance a kingship legitimated by justice to all. Sulh‑i‑kul was not mere tolerance; it was an administrative philosophy, a public pedagogy, and an ideal of citizenship under a capacious crown—one that continues to offer a grammar for plural democracies searching for shared futures.