Fatehpur Sikri is arguably the most enigmatic city in Indian history. Built by Emperor Akbar in 1571 to celebrate the birth of his son, it served as the glorious capital of the Mughal Empire for only 14 years before being suddenly abandoned. Today, it stands perfectly preserved as a "Ghost City," a frozen moment in time where red sandstone palaces, grand mosques, and intricate pavilions whisper stories of a king who tried to unify all religions. Unlike the Taj Mahal’s marble elegance, Fatehpur Sikri is robust, experimental, and uniquely Indo-Islamic.| Feature | Details |

| Location | 37 km from Agra, Uttar Pradesh |

| Built By | Emperor Akbar (1571–1585) |

| UNESCO Status | World Heritage Site (1986) |

| Architecture | Fusion of Persian, Hindu, and Jain styles in Red Sandstone |

| Key Monument | Buland Darwaza (World’s highest gateway) |

| Current Status | Abandoned “Ghost City” (Best preserved Mughal complex) |

1. The Origin Story: A King’s Desperation

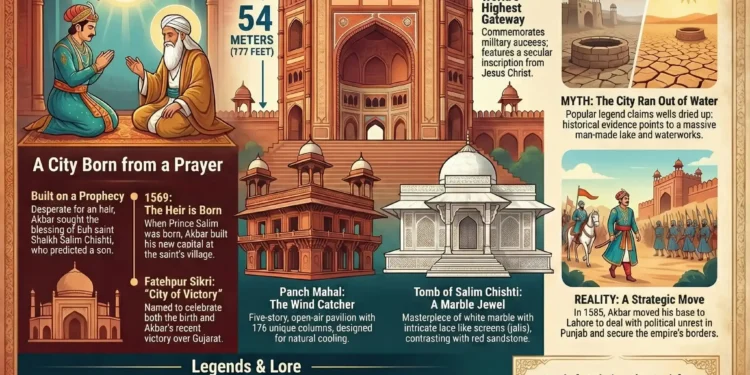

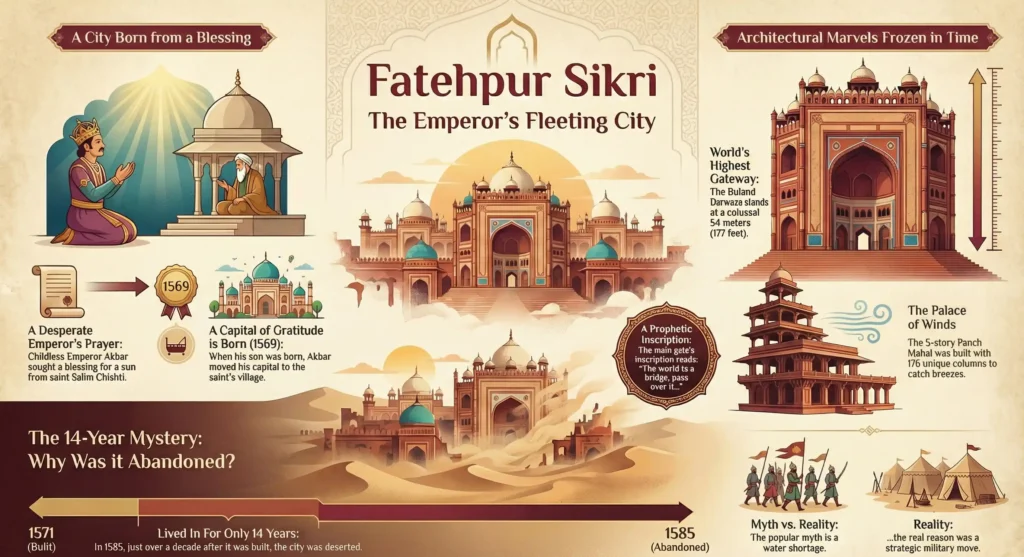

In the 16th century, Akbar the Great controlled a vast empire but lacked one thing: an heir. Desperate, he walked barefoot to the cave of the Sufi saint Shaikh Salim Chishti in the village of Sikri. The saint predicted the birth of a son. When Prince Salim (later Emperor Jahangir) was born in 1569, an overjoyed Akbar decided to move his entire capital from Agra to this ridge, naming it Fatehpur (“City of Victory”).

2. Architectural Marvels: What to See

The city is a masterclass in Indo-Islamic architecture, blending Persian domes with Hindu pillars and Jain brackets.

A. Buland Darwaza (“The Gate of Magnificence”)

Standing at a colossal 54 meters (177 feet), this is the highest gateway in the world. It was added in 1575 to commemorate Akbar’s victory over Gujarat. The inscription on the archway is fascinatingly secular, quoting Jesus Christ: “The world is a bridge, pass over it, but build no houses upon it”—a haunting foreshadowing of the city’s short life.

B. Tomb of Salim Chishti

In the middle of the vast red sandstone courtyard lies a jewel of white marble. This is the tomb of the saint who blessed Akbar. It is famous for its intricate marble jalis (screens) that look like delicate ivory lace. To this day, childless couples tie red threads here, hoping for a miracle.

C. Panch Mahal (“Five-Level Palace”)

This open, five-story pavilion resembles a Buddhist temple. It narrows as it rises, designed as a “wind catcher” (badgir) to cool the royal family during summer evenings. It famously features 176 columns, no two of which are alike.

| Monument | Meaning / Purpose | Key Feature |

| Buland Darwaza | “Gate of Magnificence” | World’s highest gateway (54m); commemorates Gujarat victory. |

| Tomb of Salim Chishti | Resting place of the Sufi Saint | Stunning white marble jalis (screens) amidst red sandstone. |

| Panch Mahal | “Five-Level Palace” | A 5-story wind tower with 176 unique columns; used for cooling. |

| Diwan-i-Khas | Hall of Private Audience | Features a single central pillar symbolizing Akbar’s dominion. |

| Jodha Bai’s Palace | Harem / Queen’s Palace | The largest residential complex; blends Hindu and Islamic styles. |

| Anup Talao | “Peerless Pool” | A central water tank where the legendary musician Tansen performed. |

3. The Great Mystery: Why was it Abandoned?

In 1585, just 14 years after its completion, Akbar packed up his court and left, never to return.

- The Water Theory: The popular story is that the city ran out of water. However, historians argue that the city had a massive man-made lake and complex waterworks.

- The Political Reality: The real reason was likely strategic. Unrest in the Punjab region forced Akbar to move his base to Lahore to secure the empire’s borders. By the time he returned to the north in 1598, he settled back in Agra, leaving Fatehpur Sikri to the ghosts.

3 Ancient Secrets of Indian Rock-Cut Architecture: A Journey Through Stone

5. Curious Indian Fast Facts (Anecdotes)

- The Human Chessboard: In the Diwan-i-Khas courtyard, there is a giant board game carved into the floor. Legend says Akbar played Pachisi here using slave girls dressed in different colors as living chess pieces!

- The Central Pillar: The Diwan-i-Khas (Hall of Private Audience) features a single, massive pillar in the center that branches out to support the emperor’s seat. It symbolizes Akbar’s dominance over the four corners of his empire.

- The Secret Tunnel: Rumors persist of a tunnel connecting the Fatehpur Sikri fort directly to the Agra Fort (37km away), built for emergency escapes, though it has never been excavated or proven.

6. Practical Travel Guide

Best Time to Visit:

- Winter (November to February) is ideal. The red sandstone heats up unbearably in summer (up to 45°C).

Timings & Tickets:

- Open: Sunrise to Sunset (Daily).

- Tickets: ₹50 (Indians), ₹610 (Foreigners).

- Pro Tip: It is best done as a day trip from Agra. The drive takes about 1 hour.

Mughal Gardens: Where Geometry Meets Paradise (A History & Travel Guide)

7. Conclusion: The World is a Bridge

Fatehpur Sikri remains a poignant reminder of the impermanence of power. It was built with the hope of a dynasty but abandoned for the safety of an empire. Walking its empty corridors today, you feel the ambition of Akbar frozen in stone—grand, inclusive, and ultimately, fleeting.

To explore another masterpiece of Mughal design that celebrated life rather than power, read our guide to the Mughal Gardens of India.

If you think you have rememberd everything about this topic take this QUIZ

Results

#1. What was the primary motivation for Emperor Akbar to build a new capital at the site of Sikri?

#2. The Buland Darwaza, the world’s highest gateway, was added to Fatehpur Sikri to commemorate which specific event?

#3. According to the provided text, what is the most likely historical reason for the abandonment of Fatehpur Sikri just 14 years after its completion?

#4. What was the unique architectural function of the five-story Panch Mahal?

#5. The inscription on the Buland Darwaza, quoting Jesus Christ, is described as a foreshadowing of what aspect of Fatehpur Sikri’s history?

#6. Which structure within Fatehpur Sikri is noted for being made of white marble, creating a stark contrast with the surrounding red sandstone buildings?

#7. According to a legend mentioned in the text, what did Akbar use as living game pieces for the game of Pachisi?

#8. What symbolic meaning is attributed to the massive, single pillar in the center of the Diwan-i-Khas (Hall of Private Audience)?

Why was Fatehpur Sikri abandoned?

While popular legend blames water scarcity, historians believe Akbar abandoned it in 1585 to move his capital to Lahore for military campaigns to secure the northwest frontier.

What is the height of Buland Darwaza?

It stands approximately 54 meters (177 feet) tall from the ground level, making it the highest gateway in the world.

Who built the Tomb of Salim Chishti?

Emperor Akbar commissioned the original tomb, but later Mughal emperors, including Jahangir, added the exquisite white marble and mother-of-pearl decorations.

How far is Fatehpur Sikri from Agra?

It is located approximately 37 to 40 kilometers west of Agra and can be reached in about an hour by road.