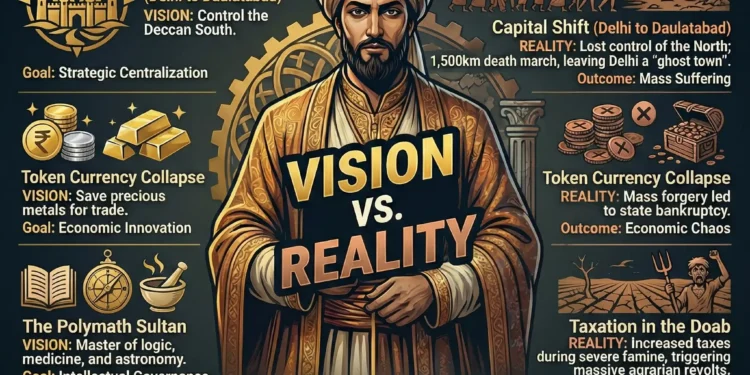

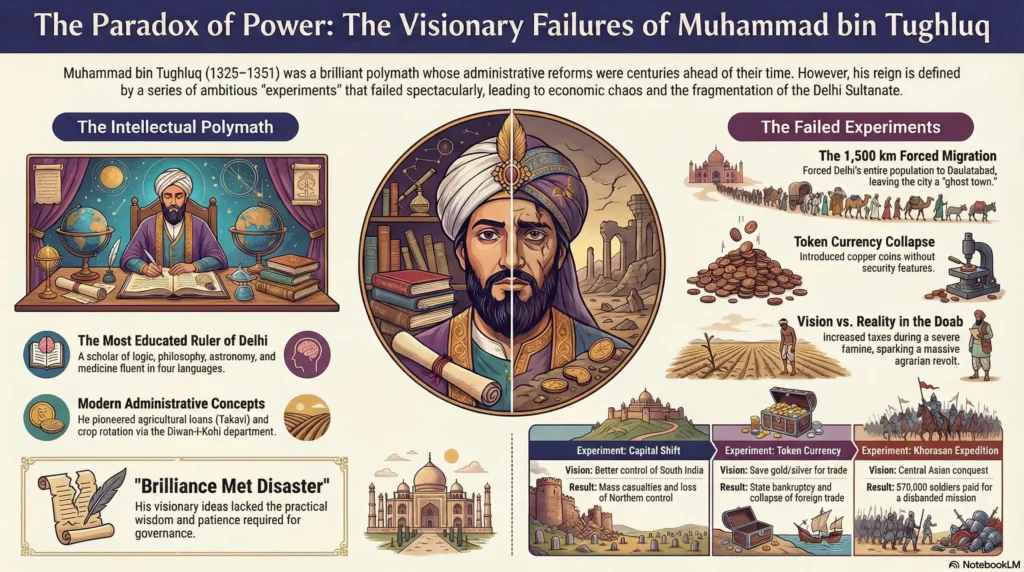

Muhammad bin Tughluq (ruled 1325–1351) is one of the most enigmatic figures in Indian history. A scholar of logic, philosophy, mathematics, and medicine, he ascended the throne of the Delhi Sultanate with grand visions of a centralized, pan-Indian empire. However, his reign is defined by five ambitious "experiments" that failed spectacularly due to poor execution and lack of public trust. These included the Transfer of Capital from Delhi to Daulatabad, the introduction of Token Currency, and the Taxation in the Doab. While his administrative reforms were centuries ahead of their time, they caused immense suffering and economic chaos. His reign saw the fragmentation of the Sultanate, with the rise of the Vijayanagara Empire and the Bahmani Sultanate. He died in 1351, fighting rebels in Sindh, with the historian Badauni famously writing, "The King was freed from his people and they from their King."| Feature | Details |

| Reign Dates | 1325 – 1351 AD |

| Birth Name | Jauna Khan (Ulugh Khan) |

| Dynasty | Tughlaq Dynasty |

| Predecessor | Ghiyas-ud-din Tughluq |

| Successor | Firoz Shah Tughluq (Cousin) |

| Capital Shift | Delhi to Daulatabad (Devagiri) |

| Famous Visitor | Ibn Battuta (Moroccan Traveler) |

| Key Failure | Token Currency Experiment |

| Department Founded | Diwan-i-Kohi (Agriculture) |

The Intellectual Giant

Unlike many medieval rulers who were mere warriors, Muhammad bin Tughluq was a polymath. He was fluent in Persian, Arabic, Turkish, and Sanskrit. He debated with philosophers and studied astronomy. He was arguably the most educated ruler to ever sit on the throne of Delhi. Yet, he lacked practical wisdom and patience—traits essential for ruling a vast, diverse empire.

Reign of Akbar 1556-1605: The Golden Age of the Mughal Empire

Experiment 1: Transfer of Capital (1327)

To control the Deccan effectively, the Sultan decided to shift his capital from Delhi to Devagiri, which he renamed Daulatabad. It was centrally located and safe from Mongol invasions.

- The Error: Instead of shifting only the royal court, he ordered the entire population of Delhi—officials, scholars, sufi saints, and commoners—to migrate.

- The Result: The journey of 1,500 km was grueling. Many died on the way. Once in Daulatabad, the Sultan realized he could not control the North from the South, just as he couldn’t control the South from the North. He ordered a return to Delhi. The city of Delhi was left a “ghost town” for years.

Experiment 2: Token Currency (1329)

Inspired by paper currency in China (under Kublai Khan) and paper money in Persia, Tughluq introduced token currency. He issued bronze/copper coins that were to have the same value as silver Tankas.

- The Vision: To save silver and gold for foreign trade and military expansion.

- The Failure: The coins had no special security features. Every house turned into a mint. People paid taxes in forged copper coins and hoarded silver. Foreign trade collapsed as merchants refused the token money.

- The Withdrawal: Realizing the chaos, the Sultan withdrew the currency, exchanging every copper coin for silver from the treasury, effectively bankrupting the state.

First Battle of Panipat 1526: The Dawn of the Mughal Empire

Experiment 3: Taxation in the Doab

To replenish the empty treasury, he raised taxes in the fertile Doab region (between Ganges and Yamuna).

- The Timing: He raised taxes during a severe famine. The peasants, unable to pay, abandoned their lands and fled to the jungles. The Sultan’s soldiers hunted them down, leading to a massive agrarian revolt.

Military Blunders: Khorasan and Qarachil

- Khorasan Expedition: He raised a massive army of 370,000 soldiers to conquer Khorasan (Central Asia/Persia). He paid them one year’s salary in advance. However, diplomatic conditions changed, and the army was disbanded, draining the treasury further.

- Qarachil Expedition: He sent an army to secure the Himalayan frontier (modern Kumaon/Garhwal). The army advanced too far into the mountains and was destroyed by the bitter cold and local guerrilla attacks. Only a handful returned to tell the tale.

The Collapse of the Empire

The chaos weakened the central authority. Governors across the empire rebelled.

- South India: Harihara and Bukka founded the Vijayanagara Empire in 1336.

- Deccan: Hasan Gangu founded the Bahmani Sultanate in 1347.

- Bengal: Declared independence.By the time of his death, the Sultanate had shrunk back to North India.

Timur’s Invasion of Delhi 1398: The Massacre That Shook India

Quick Comparison Table: Alauddin Khilji vs. Muhammad bin Tughluq

| Feature | Alauddin Khilji (1296–1316) | Muhammad bin Tughluq (1325–1351) |

| Market Policy | Strict Price Control (Successful) | Token Currency (Failed) |

| Capital | Stayed in Delhi (Siri Fort) | Shifted to Daulatabad & back |

| Army Payment | Cash Salaries (Low but fixed prices) | Paid in advance for Khorasan (Failed) |

| South India | Raided for wealth, didn’t annex | Annexed and tried to rule directly |

| Religion | Separated State from Religion | Scholarly but confused relations with Ulema |

| Legacy | Saved India from Mongols | Fractured the Delhi Sultanate |

Curious Indian: Fast Facts

- Ibn Battuta: The famous Moroccan traveler visited India during his reign. Tughlaq appointed him the Qazi (Judge) of Delhi. Ibn Battuta’s book, Rihla, is the primary source of information about this era, describing the Sultan as a man who “loved to give gifts and shed blood.”

- Diwan-i-Kohi: Realizing the agricultural crisis, Tughlaq set up a separate department for agriculture (Diwan-i-Kohi) to give loans (Takavi) to farmers and introduce crop rotation—a modern concept that failed due to corrupt officials.

- Mongol Invasion: The Mongols under Tarmashirin invaded right up to Meerut. Tughlaq reportedly bribed them to turn back, showing how weak his military position had become.

Conclusion

The Reign of Muhammad bin Tughluq is a tragedy of intellect without pragmatism. He envisioned a unified currency, a central capital, and a scientific tax system. Today, we use token currency (paper money), we have shifting administrative centers, and we have agricultural loans. He was right, but he was 500 years too early. His failure teaches that in governance, the “how” is just as important as the “what.”

Foundation of the Vijayanagara Empire: The Rise of Hampi

If you think you have remembered everything about this topic take this QUIZ

Results

#1. Muhammad bin Tughluq attempted to shift the capital from Delhi to which city, renaming it Daulatabad?

#2. Which famous Moroccan traveler visited India during Tughluq’s reign and served as the Qazi of Delhi?

#3. What was the main reason for the failure of the “Token Currency” experiment?

#4. To help farmers and improve agriculture, which new department did Muhammad bin Tughluq establish?

#5. The disastrous military expedition aimed at conquering Central Asia, where soldiers were paid a year in advance, was known as:

#6. Which two major empires rose in the South due to the weakening of the Sultanate during Tughluq’s reign?

#7. Muhammad bin Tughluq’s decision to raise taxes in the Doab region failed disastrously because:

Why is Muhammad bin Tughluq called the “Wisest Fool”?

He is called so because while his ideas (token currency, central capital) were intellectually sound and visionary, his implementation was impractical and disastrous, causing immense suffering.

Where did he shift the capital?

He shifted the capital from Delhi to Daulatabad (Devagiri) in the Deccan.

What was the token currency experiment?

He introduced copper/brass coins that had the same value as silver coins. It failed due to mass forgery and lack of government control over minting.

Which famous traveler visited his court?

Ibn Battuta from Morocco visited his court and served as a judge for eight years.

Which major empires rose during his reign due to rebellions?

The Vijayanagara Empire (1336) and the Bahmani Sultanate (1347) rose after rebelling against his rule.