Introduction

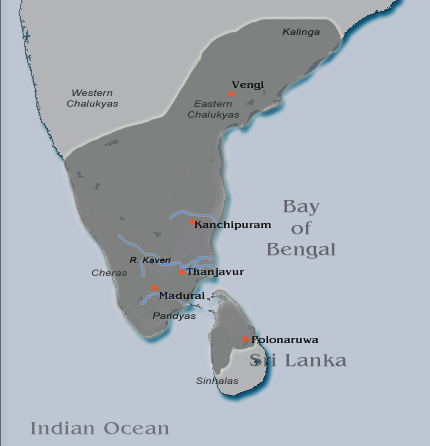

Raja Raja Chola I (r. 985–1014 CE), born Arulmozhi Varman, transformed the medieval Chola state into a centralized, thalassocratic empire that dominated peninsular India and projected power across the Indian Ocean trade routes to Sri Lanka, the Maldives, and Southeast Asian littorals. Combining meticulous internal reorganization with selective, high‑impact campaigns, he standardized revenue and record‑keeping, sponsored monumental temple architecture (notably the Brihadīśvara at Thanjavur), and curated a maritime policy that turned the Coromandel into a long‑distance commerce hub. His rule set the administrative and naval foundations that his son Rajendra I would scale into transoceanic expeditions, while inscriptions and copper‑plate charters preserve an unusually granular state archive unmatched by most contemporaries.

Political ascent and early consolidation

Ascending after the turbulent demise of his elder brother Aditya Karikāla, Raja Raja initially prioritized consolidation over spectacle—an approach visible in the early paucity of triumphalist hero‑stone inscriptions compared to the meticulous notation of surveys, grants, and appointments. Rather than overextend, he secured the Kaveri delta heartland, rebalanced relations with residual Chola–Pallava–Pandya elites, and recalibrated coastal defenses. This methodical “house‑in‑order” phase underwrote later offensives; it also signaled a ruler who understood that durable sovereignty required cadastral clarity, predictable taxation, and reliable command chains before campaigning far afield.

Administrative architecture and record culture

Standardized surveys: A realm‑wide land survey measured fields, classified soils, and cataloged irrigation, converting heterogeneous local practice into a consistent fiscal map; named officials and procedures are preserved on temple walls and copper plates.

Collegial village institutions: Brahmadeya and non‑Brahmin sabhas/ur assemblies, with elected committees (vari, kudumbu) for tank upkeep, tax collection, and justice, were embedded in royal charters—tying local stewardship to imperial goals.

Temple as archive: Major temples functioned as fiscal registries and trust banks; endowments and leases were literally inscribed in stone, creating an enforceable, public ledger culture that stabilized property rights and dispute resolution.

Officers and oversight: Revenue (puravu vari), audit, and military bureaus were layered from royal secretariat to nadu/kurram tiers, enabling vertical accountability and lateral coordination across agrarian, artisanal, and port nodes.

Campaigns: south, west, and overseas

Pandya–Chera axis: Initial campaigns neutralized the Pandyas and cut into the Chera sphere in Kerala, securing the spice/pepper ports and the Palghat–ghat corridors to the Arabian Sea; the decapitation of a Chera monarch in battle is noted in later memory as emblematic of the turn westward.

Sri Lanka (Laṅkā): Chola arms occupied northern and central Sri Lanka to control resources and sea lanes; although direct rule proved contested and rebellion‑prone, the occupation anchored naval logistics and pearl/copper flows vital to temple endowments and bronzes.

Maldives and island chains: Operations described as subduing the “twelve thousand islands” (often read as the Maldives) extended surveillance over mid‑oceanic waypoints that stitched Red Sea–Gulf traffic to Coromandel entrepôts.

China mission and Straits rivalry: A trade embassy to the Song court and pressure on Śrīvijaya’s networks signaled a conscious bid to insert the Cholas into East Asian circuits while contesting Malay choke points through diplomacy backed by naval credibility.

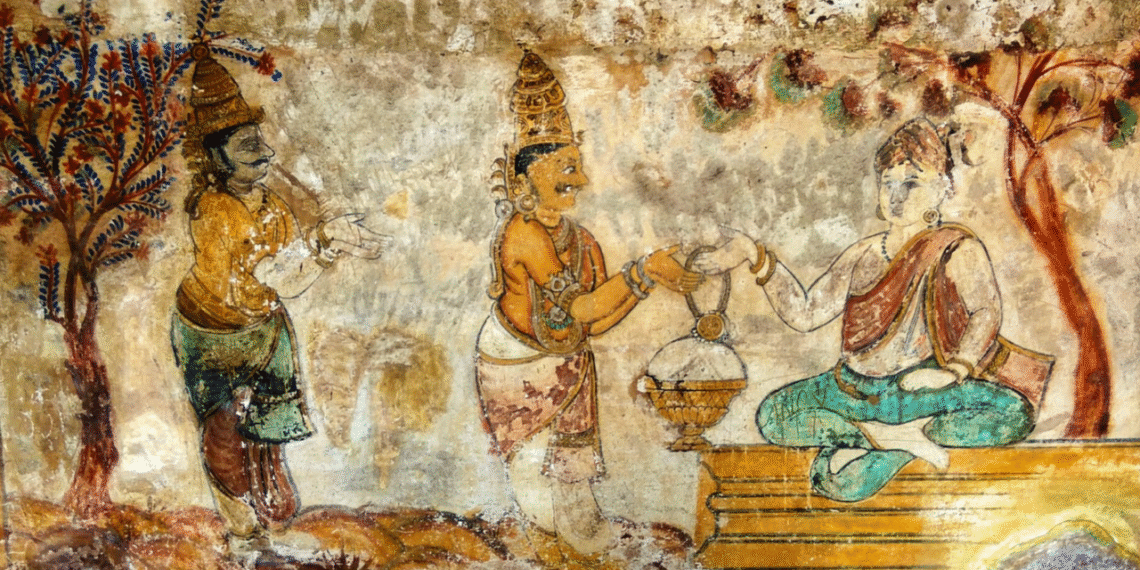

Thanjavur and the Brihadīśvara complex

The Thanjavur Brihadīśvara (c. 1010 CE) was both a ritual center and a state engine: its endowment inscriptions list land grants, lamp‑oil provisions, dancer‑musician rosters, craft guild arrangements, and tax earmarks—an administrative snapshot mapped onto sacred space. Architecturally, its soaring vimāna, granite engineering, and sculptural program broadcast imperial capability; ritually, it fused Śaiva kingship with civic redistribution, ensuring temple kitchens, festivals, and public works radiated material benefits. As an archive, the complex preserves the very names of surveyors, donors, and committees—evidence of an unusually transparent governance ethos that leveraged religion as institutional infrastructure.

Fiscal system, irrigation, and guild economy

Revenue design: Assessment tied to measured acreage, soil class, and water access, with remissions for new clearings and repairs; hypothecated taxes funded tanks, sluices, and canals, while temple endowments diversified local credit and welfare.

Irrigation complex: The Kaveri–Vennar–Kollidam system’s weirs and tanks expanded cultivation risk‑adjusted by committee maintenance mandates recorded on stone, reducing variance and stabilizing surplus extraction.

Guilds and ports: Weavers, metalworkers, and merchant guilds (e.g., Ainnūrruvar) integrated inland craft to ports like Nagapattinam and Kaveripattinam; customs points and coastal fortlets formed a revenue spine linking agrarian hinterlands to maritime demand.

Naval policy and Indian Ocean strategy

Raja Raja’s navy was not a permanent blue‑water fleet in the modern sense; rather, it was a modular, campaign‑assembled capability pairing riverine craft, coastal transports, and escort squadrons with army detachments for amphibious thrusts. The key was command of littorals and sea lanes at critical seasons: choke points near Sri Lanka, the Maldives, and the Straits were brought under watch, convoys were organized, and hostile nodes were raided or occupied when they threatened toll revenues or alliance networks. Diplomatic missions to China and pressure on Śrīvijaya communicated a deterrent posture that multiplied merchant confidence and imperial prestige.

Literacy, inscription, and royal self‑fashioning

While general literacy likely remained restricted, the Chola state’s inscriptional practice functioned as a “public reading” culture: scribes read out grants and bylaws during assemblies, ensuring broad awareness of obligations and immunities. Palm‑leaf records preceded stone engraving; although fragile, curated libraries (e.g., later Sarasvati Mahal at Thanjavur) preserved manuscripts, and some copper‑plate charters survive. Royal titles and epithets, solar‑dynasty claims, and choreographed pageantry projected a carefully crafted image: not merely conqueror, but regulator, patron, and guarantor of social order—an early mastery of what would now be called state communications.

Religion and plural patronage

A Śaiva devotee, Raja Raja endowed Śiva temples lavishly yet permitted and occasionally supported Buddhist and Vaiṣṇava institutions, especially where trade diplomacy warranted (e.g., patronage at port‑facing shrines and contacts with Sri Lanka’s Buddhist landscape). This was pragmatism, not mere ecumenism: a port’s ritual ecology affected merchant traffic, guild endowments, and regional alliances. Animal‑sacrifice limits, festival provisioning, and welfare kitchens reinforced a kingly ethic of protection and redistribution tied to ritual calendars and civic rhythms.

Legacy and Rajendra’s scaling up

Raja Raja’s greatest legacy was systemic: cadastral clarity; audit trails; temple‑archival governance; amphibious doctrine; and a Coromandel‑centered trade geography. Rajendra I could therefore pivot from consolidation to projection—up the Ganga for the Gaṅgaikondacolapuram inscriptional feats and across the Straits to chastise Śrīvijaya—because the fiscal and naval scaffolding already existed. Later Chola rulers rode this institutional momentum even as regional contestation returned; the archive endures as both memory and method.

High‑yield anchors

Dates and persona: Arulmozhi Varman crowned c. 985 CE; reign ends 1014 CE; successor Rajendra I.

Administrative hallmark: Empire‑wide land survey, standardized record‑keeping on temple walls/copper plates; village committees integrated into charters.

Campaigns: Pandyas/Cheras subdued; Sri Lanka occupied (resource/route control); Maldives targeted for waypoints; China mission; pressure on Śrīvijaya corridors.

Monument‑archive: Brihadīśvara, Thanjavur (c. 1010); inscriptions list endowments, rosters, and bylaws; temple as fiscal engine and public ledger.

Economy: Irrigation‑anchored agriculture; guild‑port integration (Nagapattinam, Kaveripattinam); customs and toll‑based revenue spine.

Naval strategy: Seasonal, modular amphibious forces for littoral control and convoy protection; deterrent diplomacy with East/Southeast Asia.

Brihadisvara Temple built by Rajaraja I, a UNESCO World Heritage Site | Source: Wikipedia

Conclusion

Raja Raja Chola I fused cadastral precision, temple‑archival governance, irrigation‑fed revenue, and modular seapower to turn a regional kingdom into a maritime‑minded empire. His conquest program was selective but strategic, aimed at ports, passes, and sea lanes that multiplied fiscal returns and diplomatic reach; his monumental building inscribed administration into stone, making policy legible and durable. In handing Rajendra a surveyed, solvent, and ocean‑literate state, he ensured the Cholas’ long arc across South and Southeast Asia—an imperial grammar of rule that married devout ritual to hardheaded logistics, and sacred architecture to state capacity.