Rajasthani miniature painting is a classical Indian art form that flourished between the 16th and 19th centuries, particularly in the Hadoti region's Bundi and Kota kingdoms. While the Bundi school is celebrated for its lyrical romanticism and Ragamala (musical) illustrations, the Kota school is distinct for its kinetic portrayals of royal hunts and dense jungles. These intricate works are characterized by their use of nature to reflect human emotions—using symbols like peacocks and lightning—and are created using precise single-hair brushes and pigments derived from precious stones and minerals.| Fact Category | Details |

| Art Form | Rajasthani Miniature Painting |

| Primary Region | Hadoti (Bundi and Kota Kingdoms) |

| Key Themes | Ragamala (Music), Shrngara (Romance), Royal Hunts |

| Peak Period | 16th – 19th Century |

| Notable Feature | Nature as a mood-setter; precise brushwork |

| Major Schools | Bundi (Lyrical) & Kota (Action-oriented) |

The World in a Grain of Sand

Imagine holding a world in the palm of your hand—a world so vivid that you can almost hear the thunder of monsoon clouds and feel the cool spray of a rushing river. This is the magic of Rajasthani miniature painting, an art form that defies the limitations of scale to deliver a massive emotional impact. Originating in the royal courts of northwestern India, these intricate masterpieces are more than just images; they are portable storybooks that capture the pulse of a bygone era.

For centuries, the Rajput courts were centers of power, culture, and artistic patronage. Among the many schools that flourished, the Hadoti region—comprising the kingdoms of Bundi and Kota—developed a visual language that was distinct, vibrant, and deeply moving. Unlike the stiff formality often seen in royal portraits of other regions, the artists here breathed life into the landscape itself. They created a realm where the forests breathe, peacocks cry out in longing, and the very sky changes color to match the mood of a lover’s heart.

Today, we peel back the layers of history to understand how these artisans, working with brushes as fine as a single squirrel hair, managed to encode the complexities of human experience onto paper. It is a journey into a land of “visual poetry,” where every stroke has a meaning and every color tells a story.

The Canvas of the Hadoti Region: Where Geography Meets Art

To truly appreciate these paintings, one must first understand the land that birthed them. The Hadoti region is not a barren desert but a land nestled amidst thick forests, shimmering lakes, and rolling hills. This unique geography imprinted itself deeply onto the artistic consciousness of the Bundi school of painting and its sister school in Kota.

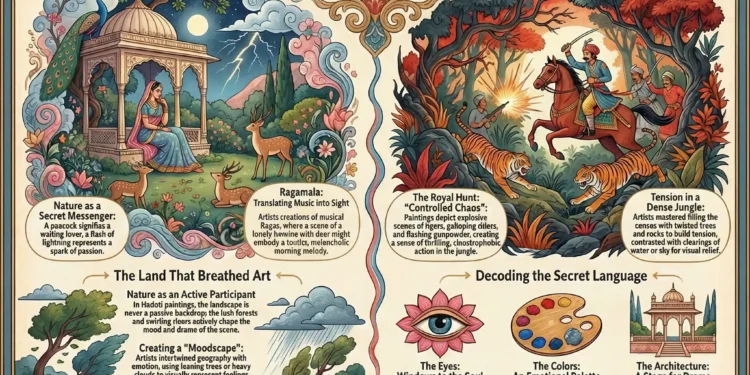

Nature in these paintings is never just a passive backdrop. It is an active participant in the drama. The lush vegetation, the swirling eddies of the river, and the density of the jungle are depicted with such intensity that they set the psychological tone of the scene. When you look at a Rajasthani miniature painting from this region, you are seeing the terrain through the eyes of someone who revered it. The artists didn’t just paint trees; they painted the feeling of being in a dense, magical forest where anything could happen.

This connection to the land allowed the artists to create a “moodscape.” If the painting depicts a scene of longing, the trees might appear to lean toward one another, or the sky might be heavy with dark, rain-laden clouds. This intertwining of geography and emotion is what gives the Hadoti style its enduring power.

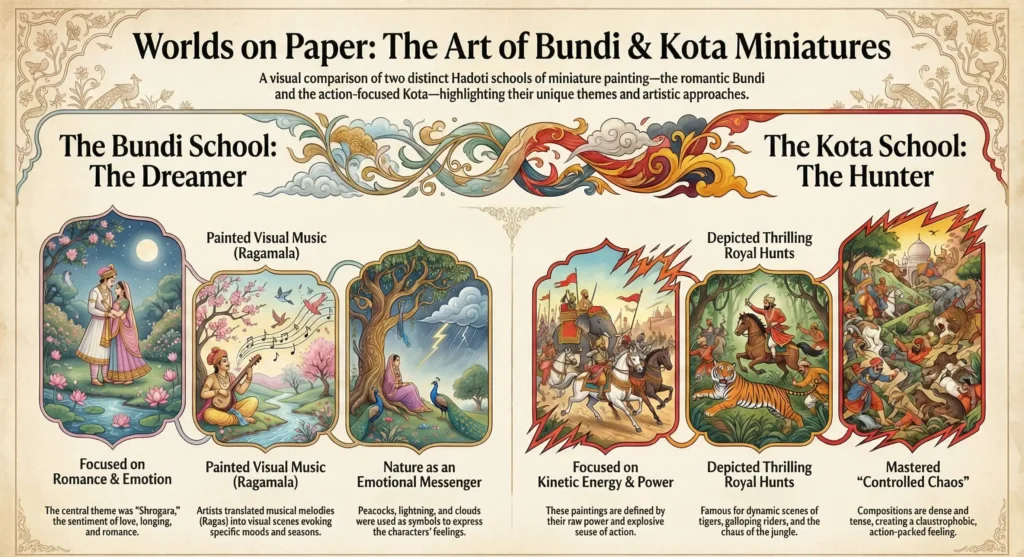

The Bundi School: The Symphony of Colors

The Bundi school of painting is often described as the “dreamer” of the Rajasthani tradition. Emerging in the late 16th century, it blended the precision of Mughal influence with the vibrant, emotional palette of the Deccan and the local Rajput spirit. But what sets Bundi apart is its obsession with Shrngara—the sentiment of romance and love.

The Melody of Ragamala

One of the most fascinating aspects of the Bundi school is the Ragamala paintings. These are not just illustrations; they are visual representations of music. In Indian classical music, a Raga is a melodic framework meant to evoke a specific mood, season, or time of day. The Bundi artists took on the incredible challenge of translating these sounds into sight.

For example, in a painting of Todi Ragini, you might see a lonely heroine playing a veena (a string instrument) in a lush grove, attracting wild deer with her music. The scene isn’t just “a woman in a forest”; it is the visual embodiment of the morning melody, tender and melancholic. The colors used—often saturated blues, reds, and yellows—vibrate with the same energy as the musical notes. It is a synesthetic experience where the viewer is invited to “hear” the painting.

Nature as the Messenger

In Bundi paintings, nature does the talking when the subjects cannot. A peacock perched on a roof isn’t just a bird; it is a classical symbol of a lover waiting for their beloved. The flash of lightning in the background represents the sudden, electrifying spark of passion. The artists developed a complex lexicon of symbols where water, flora, and fauna all conspired to tell the story of the human heart.

The Kota School: The Pulse of the Jungle

While Bundi was the dreamer, the Kota school of painting was the hunter. Though the two styles are closely related—sharing a love for lush landscapes—Kota paintings eventually forged a distinct identity defined by kinetic energy and raw power.

The Thrill of the Royal Hunt

Under rulers like Umed Singh in the 18th and 19th centuries, the Kota atelier became famous for its hunting scenes. These are not static portraits of kings posing with trophies. They are explosive snapshots of action. Imagine a canvas filled with a dense, impenetrable jungle. Suddenly, a tiger breaks cover, and the scene erupts into chaos. Riders gallop at full speed, matchlocks flash with gunpowder smoke, and lances are poised for the strike.

The Kota artists mastered the art of “controlled chaos.” They filled their compositions with scrub, rocks, and twisted trees, creating a sense of claustrophobia and tension. Yet, amidst this density, they cleared spaces of silvered water or powder-blue skies to give the eye a moment to breathe. These paintings served a dual purpose: they were records of royal bravery, effectively court propaganda, but they were also artistic triumphs that captured the wild, untamable spirit of nature.

Decoding the Secret Language of the Brush

Part of the joy of viewing a Rajasthani miniature painting lies in decoding its symbols. These works were made for an elite audience who understood the subtle cues, but for the modern viewer, they can seem like a mystery.

- The Eyes: You will often notice the large, lotus-shaped eyes of the figures. This was an ideal of beauty, but also a way to convey expressiveness in a small space. A sidelong glance could speak volumes about a character’s intent.

- The Colors: Color was never random. Intense primary colors—reds, yellows, blues—were used to heighten emotional impact. A red background might signify passion or anger, while a cool blue could suggest devotion or the divine presence of Lord Krishna.

- The Architecture: The pavilions and terraces depicted are often inspired by Deccani architecture, featuring intricate domes and niches. These structures frame the action, turning a balcony into a stage for a romantic tryst or a religious ritual.

The Silent Masters Behind the Curtain

We often speak of the kings who commissioned this art, but what of the artists? These workshops were collaborative hives of activity. It wasn’t usually a solitary genius toiling away in an attic; it was a team effort. There were designers who sketched the composition, colorists who ground the semi-precious stones and gold to make the pigments, and scribes who added the poetic verses.

These artisans were masters of their craft, blending influences from the Mughal courts, the Deccan, and their own local traditions to create something entirely new. They worked with materials that required immense patience—brushes made from the hair of kittens or squirrels, and paper polished with agate until it shone like glass. Their dedication preserved the history of the Rajput courts not in dry text, but in living color.

3 Ancient Secrets of Indian Rock-Cut Architecture: A Journey Through Stone

Why These Miniature Worlds Matter Today

In our fast-paced digital age, where images are consumed and forgotten in seconds, Rajasthani miniature painting invites us to slow down. It asks us to look closer, to notice the fine line of a sari, the individual leaves on a tree, or the expression on a tiger’s face.

These paintings remind us that art is a bridge between the past and the present. They show us that the human experiences of love, devotion, thrill, and awe at nature are timeless. Whether it is the lyrical romance of the Bundi school or the muscular energy of the Kota hunts, these portable worlds on paper continue to resonate because they speak the universal language of the soul. They are vital chapters in Indian art history that teach us to see beauty in the smallest details.

So, the next time you see a miniature painting, don’t just glance and move on. Lean in. Let the vibrant colors wash over you. Listen for the silent music of the Ragamala paintings and the roar of the hunt. You might just find that this small piece of paper holds a story as big as life itself.

| Feature | Bundi School of Painting | Kota School of Painting |

| Core Theme | Romance (Shrngara), Feminine Beauty, Music | Royal Hunts (Shikar), Action, Dense Forests |

| Nature’s Role | Lyrical and poetic; sets a romantic mood | Wild and untamed; adds tension and drama |

| Key Subjects | Ragamala series, Krishna-Lila | Hunting expeditions, processions, festivals |

| Color Palette | Vibrant reds, yellows, and golds; dreamlike | Earthier tones mixed with bright flashes; realistic |

| Emotional Tone | Soft, sensual, and contemplative | Energetic, muscular, and aggressive |

Fatehpur Sikri(1571): The Ghost City of the Mughal Empire

Curious Indian Fast Facts

Before we conclude, here are some fascinating anecdotes about the Hadoti artisans that highlight the mystery and dedication behind their craft:

- The Mystery of “Indian Yellow”: The glowing yellow found in many classic Rajasthani paintings has a controversial origin. It was historically produced from the dried urine of cows fed exclusively on mango leaves. This practice, known as Gau-goli, was eventually banned due to its harmful effects on the cattle, making authentic antique “Indian Yellow” a rarity today.

- The Single-Hair Brush: The detail in these paintings is so microscopic that it defies belief. To paint the delicate eyelashes of a court dancer or the whiskers of a tiger, artists used brushes handcrafted from the hair of squirrels. For the finest lines, they would use a brush consisting of just a single hair.

- Burnished to Perfection: The paper used, known as Wasli, wasn’t just ordinary pulp. It was created by gluing multiple layers of paper together and then vigorously burnishing (polishing) it with a smooth agate stone or a conch shell. This created a surface as smooth as glass, allowing the pigments to glide effortlessly.

- The Invisible Artist: While the kings were immortalized, the artists often remained anonymous. However, eagle-eyed historians have found tiny, hidden self-portraits of artists tucked away in the corners of crowded procession scenes—a quiet way for the creator to sign their masterpiece.

Conclusion

Rajasthani miniature painting in the Hadoti region is a testament to the power of human creativity. It beautifully marries the saturated colors of the Indian landscape with the refined techniques of courtly art. While the Bundi school offers an intimate poetry of seasons and longing, the Kota school provides a window into the adrenaline of royal life. Together, they reveal how Rajput artisans translated their world—its loves, rituals, and dangers—into enduring masterpieces.

If you think you have rememberd everything about this topic take this QUIZ

Results

#1. What is the primary function of nature and the landscape in the paintings of the Hadoti region?

#2. The Bundi school of painting is particularly known for its focus on ‘Shrngara’, which refers to the sentiment of:

#3. What unique challenge did Bundi artists undertake when creating Ragamala paintings?

#4. Which characteristic best defines the artistic identity of the Kota school, especially in contrast to the Bundi school?

#5. In the symbolic language of Hadoti miniature painting, what might a peacock perched on a roof signify?

#6. How did Kota artists create a feeling of ‘controlled chaos’ in their famous hunting scenes?

#7. What was a significant non-artistic purpose of the Kota school’s hunting scenes?

#8. According to the text, the use of intense primary colors like reds and yellows in these paintings was intended to:

What is the main characteristic of Rajasthani miniature painting?

The most distinct characteristics are the use of vibrant, natural colors (derived from minerals and vegetables), intricate brushwork, and the depiction of large, expressive eyes. The paintings often feature themes from Hindu mythology, courtly life, and nature.

How are the Bundi and Kota schools different?

While both belong to the Hadoti region, the Bundi school of painting is famous for its lyrical, romantic depictions and Ragamala sets. In contrast, the Kota school of painting is renowned for its dynamic hunting scenes and dense, realistic portrayals of jungles.

What materials were used in these paintings?

Artists used paper (wasli), cloth, or ivory as a base. Pigments were created from precious and semi-precious stones like lapis lazuli, gold, silver, and plant sources. Brushes were incredibly fine, often made from a few strands of squirrel or kitten hair.

Why are Ragamala paintings important?

Ragamala paintings are unique because they are a visual crossover of art and music. They personify musical modes (Ragas) into specific scenes, characters, and moods, effectively allowing the viewer to “see” the music.

Are these paintings still created today?

Yes, many contemporary artists in Rajasthan continue to practice this traditional art form, preserving the techniques passed down through generations while sometimes introducing modern themes.