Introduction

Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha are the two most significant Islamic festivals in India, uniting communities in prayer, charity, and shared meals while reflecting distinct spiritual moments in the Islamic year. Eid al-Fitr marks the close of Ramadan’s month-long fast with thanksgiving, renewal, and Zakat al-Fitr to ensure everyone can celebrate; Eid al-Adha, the “Festival of Sacrifice,” commemorates Prophet Ibrahim’s devotion through qurbani and equitable sharing of meat with family, friends, and the poor.

Context and origins

Eid al-Fitr follows the sighting of the Shawwal new moon, ending Ramadan’s dawn-to-dusk fasting and reaffirming gratitude, self-discipline, and community solidarity.

Eid al-Adha falls on 10 Dhu al-Hijjah, the last month of the Islamic lunar calendar, coinciding with Hajj; it honors Ibrahim’s willingness to sacrifice his son, with God substituting a ram at the moment of obedience.

Key features and vocabulary

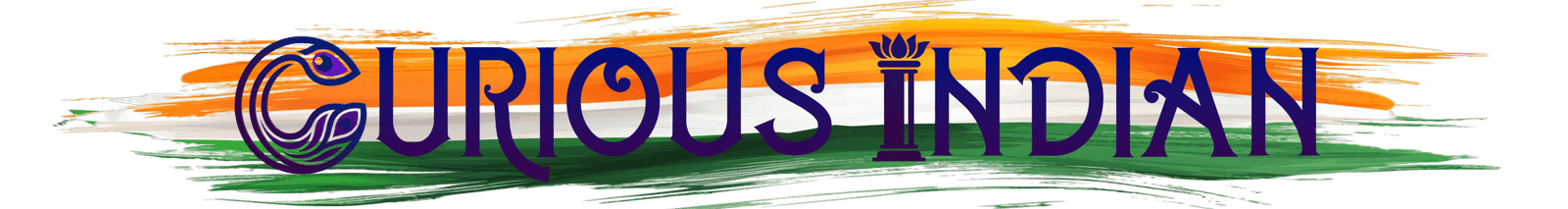

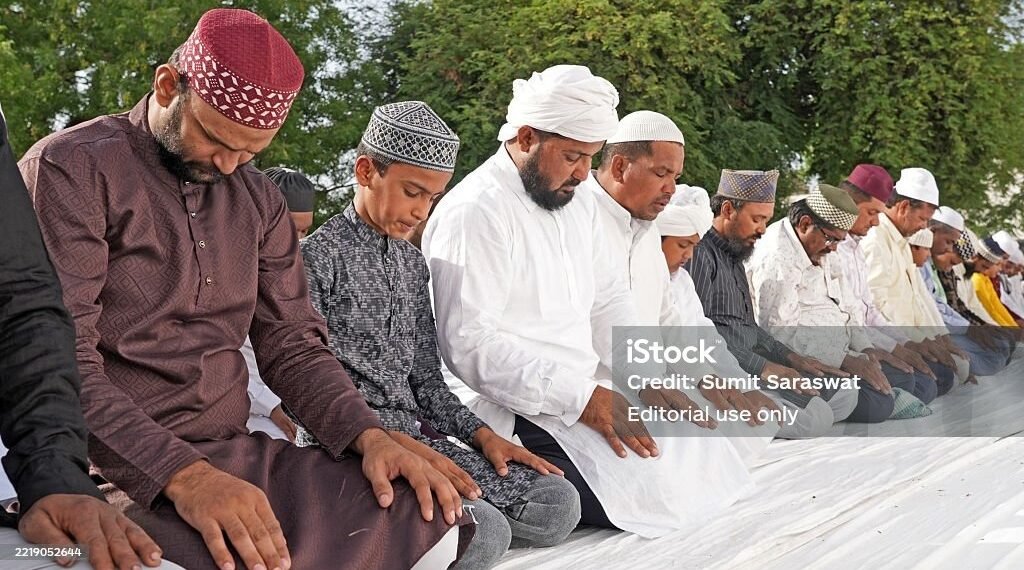

Salah al-Eid: Congregational Eid prayer (two rakaʿāt) offered in open grounds (Eidgahs) or mosques, followed by the khutbah (sermon) and communal greetings of “Eid Mubarak.”

Zakat al-Fitr (Fitrana): Mandatory charity given before Eid al-Fitr prayer to purify the fast and provide for the needy so all can partake in the day’s joy.

Qurbani/Udhiya: Ritual animal sacrifice at Eid al-Adha, with meat divided into three parts—family, relatives/friends, and the poor—symbolizing devotion, equity, and care for the vulnerable.

Eidi and hospitality: Gifts to children and visits among relatives and neighbors emphasize familial warmth and social bonding on both Eids.

Timeline and rituals

Eid al-Fitr (Festival of Breaking the Fast)

Pre-dawn preparation: Bathing, donning fresh clothes, light breakfast (often dates/dry fruits, as fasting is prohibited on Eid), and takbir recitations on the way to prayer.

Congregational prayer: Two rakaʿāt with multiple takbirs; khutbah follows the prayer (unlike Friday prayer, where sermon precedes).

Zakat al-Fitr: Disbursed before the prayer to the poor—its timing is integral; after prayer it is counted as regular charity (sadaqah).

Community celebration: Visits, Eidi, and sweets; regional specialties include sheer khurma, sevaiyan, and festive biryanis in many Indian cities.

Eid al-Adha (Festival of Sacrifice)

Morning prayer: Offered in large gatherings at mosques/Eidgahs; khutbah emphasizes Ibrahim’s obedience, compassion, and sharing.

Qurbani: Animal sacrifice (sheep, goat, buffalo, camel where permitted), performed from 10th to 12th Dhu al-Hijjah, subject to affordability and local regulation.

Distribution and meals: Meat shared in thirds—family, kin/friends, poor—followed by communal cooking (biryani, kebabs, korma) and hospitality visits.

Charity and outreach: Many families augment qurbani with food drives or donations to orphanages, reflecting the festival’s ethic of generosity and inclusion.

Differences at a glance

Meaning: Eid al-Fitr celebrates the completion of fasting (gratitude, renewal); Eid al-Adha commemorates sacrifice and submission to God (obedience, sharing).

Obligations: Zakat al-Fitr is specific to Eid al-Fitr (before prayer); Qurbani is central to Eid al-Adha for those who can afford it.

Timing: Eid al-Fitr begins Shawwal; Eid al-Adha occurs about two lunar months later during Hajj (Dhu al-Hijjah).

Tone: Eid al-Fitr is widely celebratory with sweets and visits; Eid al-Adha is more ritual-centered with qurbani and structured distribution of meat.

How India celebrates (regional lens)

Eidgahs and cityscapes: From Delhi’s Jama Masjid to Hyderabad’s Mecca Masjid and Mumbai’s Eidgah Maidan, early morning congregations fill courtyards and avenues in scenes of serene unity.

Foodways: Sheer khurma and sevaiyan at Eid al-Fitr; at Eid al-Adha, family recipes for hearty meat dishes flourish, with portions set aside for neighbors and the needy.

Community service: Mosques, NGOs, and local groups coordinate Fitrana distribution, food packets, and meat-sharing logistics to reach vulnerable communities efficiently.

Cultural pluralism: In mixed neighborhoods, interfaith greetings and shared plates—mithai boxes, sevaiyan bowls—underscore the syncretic warmth of Indian cities.

Etiquette and practical notes

For visitors: Dress modestly, allow space at prayer venues, and follow local guidance. Accept sweets or hospitality when offered; a simple “Eid Mubarak” warms hearts.

On Fitrana and qurbani: Respect the timing and purpose—Fitrana before prayer, qurbani within prescribed days; follow municipal rules on hygiene and animal welfare.

Sustainability and safety: Many communities adopt centralized qurbani facilities for hygiene; cold-chain planning helps equitable and safe meat distribution.

Contemporary relevance and legacy

Social equity: Zakat al-Fitr and qurbani’s three-way distribution operationalize compassion, ensuring inclusion at moments of joy and affirming Islam’s social ethics.

Family and identity: New clothes, Eidi, and shared meals nurture intergenerational bonds and cultural continuity in India’s diverse Muslim communities.

Civic harmony: Public Eid greetings and outreach by civic leaders and interfaith groups reinforce unity-in-diversity and the right to celebrate safely and joyfully.

Conclusion

In India, the two Eids illuminate complementary facets of faith and community. Eid al-Fitr is a gentle dawn after discipline—sweet bowls of sevaiyan, open doors, and alms that dignify the day for all. Eid al-Adha is devotion turned outward—qurbani shared in thirds, kitchens humming, and the poor remembered first. Together they weave gratitude, obedience, and generosity into lived traditions that nourish both the soul and the social fabric.