परिचय

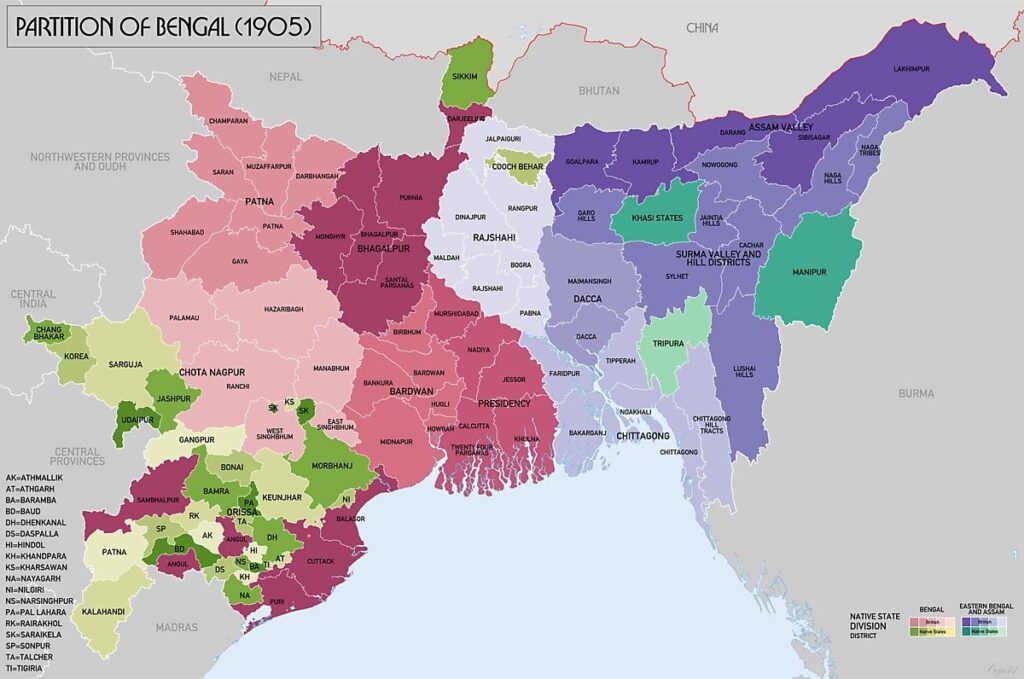

The Partition of Bengal, announced by Viceroy Lord Curzon and brought into effect on 16 October 1905, divided the vast Bengal Presidency into two parts—Western Bengal (largely Hindu-majority) and the new province of Eastern Bengal and Assam (largely Muslim-majority)—triggering the Swadeshi and Boycott movements and reshaping India’s nationalist politics until the partition’s annulment in 1911.

Why Bengal Was Partitioned

- Official rationale: “Administrative efficiency” for a province of unwieldy size (cited population ~78 million), with Curzon arguing that governance required reorganization.

- Political motive: A divide-and-rule calculus to weaken a nerve center of Indian nationalism by creating a Muslim-majority Eastern Bengal and Assam and a Hindu-majority Western Bengal.

What Changed on 16 October 1905

- Creation of Eastern Bengal and Assam with Dhaka as capital; Western Bengal retained Calcutta as capital until 1911.

- The day was marked by mass hartals, processions singing Bande Mataram, and symbolic Raksha Bandhan to emphasize Hindu–Muslim unity across the divide.

Birth of the Swadeshi and Boycott Movements

- Formal proclamation: A “Boycott” resolution at Calcutta Town Hall on 7 August 1905 launched the Swadeshi movement, urging rejection of foreign (especially British) goods and promotion of indigenous industry.

- Methods and spread: Boycott of Manchester cloth and Liverpool salt, encouragement of handloom and khadi, national education initiatives, and samitis (volunteer associations) for mobilization.

- Leadership: Early moderates like Surendranath Banerjee and G.K. Gokhale organized petitions and protest; an emergent “extremist” current (Garam Dal) pushed mass action and boycott 1905–1908, intensifying the movement’s reach and tempo.

Opposition and Unrest

- Citywide shutdowns and school boycotts greeted partition day; police and troops dispersed demonstrations, and the campaign radicalized as petitions failed to secure relief.

- The movement linked economic nationalism to political agitation, spreading beyond Bengal and revitalizing the Indian National Congress as a nationwide platform.

Annulment and Reorganization (1911)

- Reversal: Owing to sustained mass opposition, economic pressure from boycott, and political recalibration in London and Calcutta, the British annulled the partition in December 1911 under Viceroy Lord Hardinge.

- King George V’s Delhi Durbar announcement (12 December 1911) reunited Bengal on linguistic lines, separated Bihar and Orissa into a new province, restored Assam to separate administration, and shifted the imperial capital from Calcutta to Delhi, effective January 1912.

- Muslim reactions were mixed; many Bengali Muslims, who had welcomed a Muslim-majority province, felt aggrieved by the annulment, a development that fed into communal politics and the rising influence of the Muslim League (founded 1906).

Timeline (Key Dates)

- December 1903: Government decision for partition made public; discontent mounts.

- 7 August 1905: Swadeshi formally proclaimed; Boycott resolution passed at Calcutta Town Hall.

- 16 October 1905: Partition takes effect; mass protests, hartals, Raksha Bandhan solidarity.

- 1905–1908: High phase of Swadeshi and Boycott; national education and samiti activity expand.

- 12 December 1911: King George V announces annulment; capital shifted to Delhi.

- January 1912: Reorganization implemented (reunited Bengal; Bihar & Orissa separated; Assam distinct).

Why It Mattered

- Nationalist consolidation: Partition catalyzed the first mass, pan-regional economic–political movement (Swadeshi), transforming Congress from an elite petitioning body into a more activist, broad-based force.

- Economic self-reliance: Boycott and indigenous production campaigns seeded durable ideas of swadeshi and self-help that reappeared in later phases of the freedom struggle.

- Administrative legacy: The 1911 reversal redrew provincial boundaries on linguistic lines and relocated the imperial capital to Delhi, recentering imperial governance and symbolism.

- Communal politics: The creation and then dissolution of a Muslim-majority province intensified communal consciousness in eastern India, shaping politics in the years ahead.

Key Figures and Places

- Lord Curzon (Viceroy, 1899–1905): Architect and defender of the partition.

- Surendranath Banerjee, G.K. Gokhale: Led early constitutional protests and mobilization.

- Dhaka (capital of Eastern Bengal and Assam), Calcutta (Bengal capital; imperial capital until 1911), Delhi (imperial capital after 1911).

Quick Facts

- Effective date of partition: 16 October 1905.

- New unit created: Eastern Bengal and Assam (Dhaka capital).

- Movement launched: Swadeshi and Boycott (from 7 August 1905).

- Annulment: Announced 12 December 1911; implemented January 1912.

- Capital shift: Calcutta to Delhi (1911).

Further Notes

- The Swadeshi movement’s mass rituals, cultural mobilization (Tagore’s songs, Bande Mataram), and national education drives gave the anti-partition struggle a distinctive civil-society character with enduring ideological impact.

- The 1909 Morley–Minto reforms (separate electorates) intersected with the communal consequences of partition politics, attempting to stabilize rule amid rising mobilization.

Each of these developments—Curzon’s administrative case, the communal geometry of the new province, Swadeshi’s mass economic politics, and the 1911 reorganization—made the 1905 Partition of Bengal a pivotal crucible for modern Indian nationalism and colonial statecraft.

इस बारे में प्रतिक्रिया दें